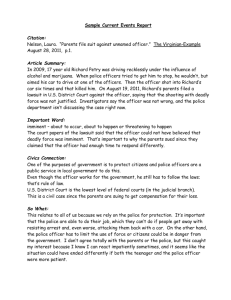

Compendium of Case Studies

advertisement