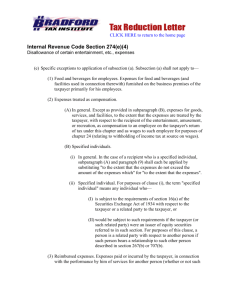

Introduction

advertisement