12_9_13fc meeting - The University of Texas at Austin

advertisement

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

Hillary Hart (chair, distinguished senior lecturer, civil, architectural, and environmental engineering):

{0:00:40.0}

Okay, let’s get started. Hi everybody, thank you for being here during this extremely busy and crazy time

of the year, I really appreciate it. Once again, our secretary is not here today so I am going to give the

Report of the Secretary. There was a memorial resolution completed for M. Michael Sharlot and really no

other items completed since the last report. What we need to do today is to approve, if we can, the

November 18 minutes. In spite of what the slide says, our last meeting was November 18. I hope you’ve

had a chance to look at the minutes so that we can vote. Because this is all transcribed, let me just remind

people again, we need you at a microphone and we need your name and department.

Alberto Martinez (associate professor, history, faculty council):

Thank you, very quickly Al Martinez, Faculty Council. I have a very brief objection to one footnote. The

only footnote in the report, it says both President [William] Powers and Vice President [Kevin] Hegarty

have acknowledged that the Shared Services planned numbers were not accurately reflected in the Shared

Services presentations and that they should be updated. I know that that’s not something that happened at

the meeting, so what I’m hoping is that this footnote does not come from an e-mail I sent Hillary. Hegarty

has spoken to me about this in private conversations; however, you know, I think that both he and Powers

should communicate directly with the Faculty Council if there’s a statement in the minutes about their

comments.

Hart:

You know it certainly didn’t come in an e-mail to me. Debbie, can you say something about the minutes

here? {0:2:27.4}

Debbie Roberts (executive assistant, office of the general faculty):

My understanding is that Dean Neikirk wanted a footnote indicating that, [Hart: that the figures need to be

revised] right, just to let faculty know that he was aware that the numbers were not correct. I think it was

discussed in the FCEC+ meeting. I don’t know…we can delete it if you all choose to have it deleted.

Hart:

Okay, let’s—let’s ask Kevin.

Kevin Hegarty (vice president and chief financial officer):

I was not at the last meeting if the comment was made there. If it was made outside of the meeting, relative

to my conversation about that, I disagree. I don’t know that…my exact comment was that the pattern of the

numbers may change. Some revenue, some expense may accelerate, may decelerate, but it’s going to be

what it’s going to be. So there is no basis for restating those numbers.

Hart:

My memory of this was that, Al you may have brought it up at the meeting and the president acknowledged

that there may be some slippage there, or some difference, but there was nothing specific, and so I think we

probably should strike that. Okay, so with the revised minutes with the footnote, the only footnote taken out,

may I have a motion to approve? Is there a second? All those in favor please say Aye. [Aye.] Opposed,

nay? [Nay.] And, abstentions? Okay, great. Passed. All right, the next part of the meeting is questions with

the president, communications with the president, questions for him. We do not have Bill Powers with us,

but we have our provost, Greg Fenves, who is going to address the questions from Blinda McClellan and

Jon Olsen. Thank you.

Gregory Fenves (professor, executive vice president and provost): {0:4:38.4}

Thank you Hillary. I’m Greg Fenves, executive vice president and provost representing President Powers,

who could not be here today. I assume everybody can read the question or has read it so I won’t repeat it.

So, since this question was submitted, I’ve worked with Patti Ohlendorf in the general counsel’s office,

looking at some of these issues. And there are two important aspects to the answer. Number one, individual

faculty own the copyright to materials that they prepare for their courses. So syllabi, reading lists, notes,

flash cards, those are copyrighted by an individual faculty member. The University does not assert

ownership or copyright of any materials prepared for a class.

1

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

So that’s going to be very important, and the second part of this is that sites like CourseHero are file

sharing sites. Some of you may remember in the 90s and 2000s there was huge controversy about music

sharing sites. What was the big one… Napster that went out of business and was forced out of business, so

there were huge changes taking place in the distribution of copyrighted material and trademark material.

That eventually led to what is known as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which I think passed about

a year or two ago. And so the new copyright act does allow the file sharing services to share files without

any liability for copyright infringement, unless the owner of the copyrighted material requests the file

sharing site to take it down. So what does this mean for CourseHero? Well, if you’re teaching a class, and

your class materials end up on the site, presumably a student in your class downloaded it from a site that

they needed to be a registered student to receive them, then uploaded them to CourseHero, CourseHero can

host that until you, as a faculty member who holds the copyright, requests CourseHero to take it down. So

the University cannot act on a faculty member’s behalf, because the University doesn’t own the copyright.

We’ve worked over the past day or two with the general counsel’s office to think about a few things that

could be done. Number one, the attorney in Patti’s office has created a template that’s basically a form.

There’s a very specific procedure for a copyright holder to request material being taken down. It’s

straightforward, but it does require action by the faculty member, the holder of the copyright, to send this to

CourseHero to request it be taken down. And CourseHero must do it, or then they do become liable for

damages, but that doesn’t prevent another student or the same student from reposting it. This is the way the

copyright act has been set up under the recent law. But, we could set up a template, educate faculty about

what are the procedures for requesting material to be taken down. But again, as the University, we can’t act

on behalf of a copyright holder unless the faculty member elects to turn copyright of the materials over to

the University, and that’s generally something we haven’t wanted and faculty haven’t wanted, because

faculty should own the copyright.

We’ve talked with the Dean of Students about an education campaign to students that when they download

material it’s for their use for their class; it can’t be distributed because it is owned by the faculty member.

In fact, if they do transmit it to CourseHero or other file sharing sites, they are violating institutional rules

and violating the honor code. So part of this is education of our student body who may be doing this. The

third thing that can be done is, if a faculty member does request it to be taken down and there’s identifying

information for a student, then Student Judicial Services can open up an investigation of the student

violating institutional rules by using material from a class in a way that they shouldn’t. Those are the

mechanisms that are available. Again, with the understanding that the faculty member owns the copyright,

and under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, these file sharing services are allowed to do things unless

they’re given notice by the copyright holder. We’re very interested in getting feedback from faculty with

these ranges of things that can be done, again, primarily an education campaign with students. Faculty can

put notices in their syllabus that students should not use material for purposes other than their material use

in the class, so their students are aware of this. Then, if enough faculty give notice to CourseHero, they may

decide that they don’t want to receive uploaded material from The University of Texas at Austin students,

and it’s just not worth the liability. Those are a number of actions that can be taken. {0:10:24.3}

On the second question about some of the material, I guess think about the student that submitted material

to a file sharing system with their name on it—you have to wonder what they were thinking—but, the

question is, is the name and EID protected under FERPA? The answer is, both of those are considered

directory information, and so those are available publicly unless the student has gone to the registrar’s

website and requested that directory information not be made public. So in general, releasing directory

information does not violate FERPA. It would depend on whether that individual student had actually gone

to the registrar’s site. But presumably, it was that student who submitted the information— although you

can never tell. So that’s where we are with file sharing services.

Blinda McClelland (lecturer, biology instructional office): [0:11:24.2]

Hi, I’m Blinda McClelland. [Fenves: yes] I’m the one that submitted the question, and I had two purposes

in doing so. First of all, because I had submitted questions to our IT people and various other people who

might have some control over this situation and haven’t received any answer. So I was a little frustrated.

2

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

Secondly, everyone I have talked to has been shocked to find out that materials that we upload to

Blackboard, that we consider to be only accessible to students, like my PowerPoints, are uploaded to

CourseHero. I think we all understand a huge difference between creating a public personal website and

uploading things. And then, you know, if a person—and by the way, people pay to download material from

CourseHero, so CourseHero’s making a profit on our material. I mean, if they’re paying for information

that they can get for free, then that’s an issue for P.T Barnum, but I think we all understand the difference

between materials that are uploaded. I had 133 results for William Powers Texas when I searched, fortyone for Bill Powers, four for Greg Fenves [Fenves: Well, there’s something suspicious there, because I

know I haven’t submit…I don’t have any materials on Blackboard] Well, your name just happened to come

up. Right, twenty-five for Hillary Hart, eight for William Beckner, seventy-five for Dean Neikirk. I don’t

know if you would consider it a good thing or a bad thingto rate how many uploads there are with your

name attached. But, I want to thank you for your answer and I really support an education outreach to the

faculty to make them aware and secondly to the students. CourseHero is just one site [Fenves: it’s just one

site, that’s correct] And I appreciate the idea of putting it in the syllabus so…

Fenves:

And back to [Hart: three minutes], back to Napster, some universities working with some of the record

companies really did go after students who had been illegally uploading. After a few of those prosecutions,

it pretty much ended Napster. I think getting the message out there that this is not something our students

should be doing, it’s violating the honor code, it’s violating institutional rules, and it’s really violating the

rights of the faculty they’re taking courses from should help. But I’ll check to see what they have with my

name on it. All right, Thank you. {0:14:13.2}

Hart:

Don’t go too far away though, because we are now at the report of the chair and I want to give you an

update on UTS 180, the System…Blinda, you got a problem? [unidentified voice speaking, inaudible] Well,

I think provost Fenves has been nice enough to impersonate Bill Powers in a prepared question, but

questions to the president are for the president, especially from the floor. I’m just going to say it has to wait

until January. You can blame me. It’s not Greg’s decision, it’s mine. Okay, thanks. So I wanted to give you

an update on 180, the System policy on Conflict of Commitment, Conflict of Interest, and Outside

Activities that has gone up to System, the model HOP language that the Faculty Council Executive

Committee worked on with legal affairs, and Neil Armstrong’s office has just gone to System I think, early

this month. The implementation of the policy is being prepared under provost Fenves’ direction so I’ve

asked him to give us an update on the implementation. Would you come up here?

Fenves: {15:42.6}

As Hillary said, our version of UTS 180 in our Handbook of Operating Procedures is now at the System

office for final approval. This is the version that, as Hillary mentioned, has gone through the Executive

Council with some changes from the model policy, but we were satisfied with it. I talked about it earlier in

a Faculty Council meeting. It’s about as good as we were going to get and a significant improvement over

the original version of UTS 180. We’re expecting System to approve our version of UTS 180 in the

Handbook of Operating Procedures. The key step now is in the implementation of UTS 180, and Neil

Armstrong in my office is working with System on that. When I looked at it about two weeks ago there was

a real problem in it and it stemmed from the fact that UT System is developing a website for faculty to

access to do the advanced approval where required and then the annual reporting. The annual reporting was

okay. The advanced approval had a major problem in my view in that it required faculty to declare

compensation for an activity in which they’re requesting approval, no matter what the conditions were. And

of course, under the policy, which we reviewed and which we submitted to UT System, compensation only

needs to be reported if it is over $5000, and if there is a “conflict of interest management plan” in effect.

That’s a very specific condition that requires reporting of compensation for that outside activity. UT

System set up this website so that it can be used by all fifteen campuses within The University of Texas

System. According to them, some campuses wanted to use the level of compensation in the determination

of whether there was a conflict of interest. We do not want to do that. The website, at least in the version I

looked at a couple of weeks ago, did not reflect the policy. So we’re working with UT System to either

modify the website or have it programmed specifically for UT Austin faculty. I haven’t heard back how

3

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

that’s working out yet, but I’ve made it clear that we want an implementation that directly follows the

requirements in the approved policy. I hope we will get that. We will get it. They are also working on

training materials to describe the policy to faculty and staff. We will scrutinize those very closely to make

sure that those do reflect the actual policy and the procedures for carrying out the policy. So that’s what the

current status is. I believe they will be doing a beta test of the website early in 2014, and I’m not clear on

this, but I think the rollout is expected in March of next year. Thank you. {0:10:06.3}

Hart:

Thank you, Greg. Last I heard was that the reporting was going to be for January through March, but it

probably won’t roll out until March, so we’ll stand by for updates on the timing. The only other thing I

want to do in my report is to let you know who the winners of the Civitatis Award are this year. I don’t

think either one of them are in the room. This is an award that was—some of you may know about this

award—this was an award that was created, I think, in 1997 to sort of honor good faculty citizenship,

faculty going above and beyond and being helpful to other faculty. I have the exact wording somewhere,

but I lost it. It’s a really wonderful award because it honors a lifetime of giving to the University in many

ways and just being a fantastic faculty citizen. I think that’s the best way to put it. And this year’s winners

are two, Larry Abraham, who was interim undergraduate dean—Larry’s here! Larry, all right. Please stand

up. [applause] Those of you who know Larry at all know how many endless hours he has worked for

undergraduate studies and for undergraduate education on this campus. Thank you Larry. And Pat Davis

from pharmacy who has been on many, many committees and done a lot of service through the years and is

probably a familiar name to a lot of you. So congratulations to both of you. [applause]

{24:04.5} Okay, no report of the chair-elect since we have no chair-elect here. No unfinished business. So I

want to move to the reports that we have under new business. With your permission, I’m going to change

the agenda a bit and ask David Laude, senior vice provost for enrollment and graduation management to

come forward before Mary [Steinhardt], who has kindly said that she would go afterwards to talk to us

about four-year graduation rate initiatives. Thank you David.

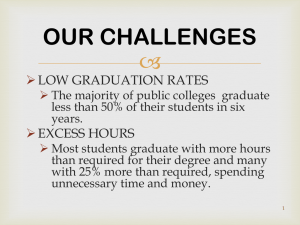

David Laude (professor, senior vice provost for enrollment and graduation management):

Thanks, Hillary for the opportunity to speak with you all today. As I understand I’m going to take about

fifteen minutes to give you a broad overview of what we’ve been doing with respect to the notion of fouryear graduation rate improvement. If you think back a few years, there has been some conversation about

how a university goes about being efficient in the way that it educates its students. There has been a long

tradition that it takes four-years to go to college, and I know that many of us probably did it in four years

not really knowing why, but we did, and we graduated and moved on.

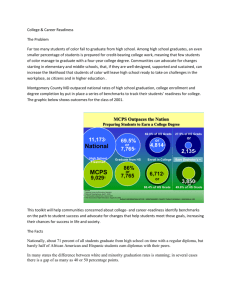

Here at UT and across the country over the last several decades, there’s developed a somewhat different

perspective of how to use college. You end up seeing lots of differences in the graduation rates for students.

Universities where it’s very expensive to go to school still have four-year graduation rates that are right at

four years. At other institutions where you have the opportunity to spend more time and where the

economic pressures aren’t as substantial, you end up tending to see students take longer to graduate. Here at

The University of Texas, we have a reasonable four-year graduation rate, the best in the state of Texas. It’s

at about 52 percent for a public university. That’s consistent with a lot of our peers such as Texas A&M,

for example, and some of the Big Ten schools. However, it’s also true that there are institutions out there

that we consider our peers who are able to graduate their students at a substantially higher rate—North

Carolina, Virginia and Michigan have four-year graduation rates around 70 percent. President Powers

found himself in conversation with others a few years ago about whether or not the University was able to

get itself from this place where we were around 52 percent up to about 70 percent and said yes, he thought

we could. He charged the task force that was chaired by Dean Diehl in liberal arts to look at ways that we

could go about doing this. That task force met over the course of many months and issued a task force

report, which said basically three things. It said: 1) we should improve orientation, 2) that we should

improve advising, and 3) that we should hire a champion for four-year graduation rates and I believe that is

me. I am the champion for four-year graduation rates. They also had a list of like a hundred really hard

things to do that would improve four-year graduation rates, and they told the champion that it would be his

or her job to do that. So that’s the job I’ve taken on. I’ve been in the provost’s office for the last eighteen

months with that particular responsibility. I should stop here though and tell you that my view of four-year

4

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

graduation rates is couched less in the notion that we’re supposed to be graduating students with a 70

percent four-year graduation rate, and more with the perspective of student success. I come out of a student

dean’s tradition, fifteen years in the College of Natural Sciences. As for me, it wasn’t really whether a

student graduated in three years or four years or five years. It was whether or not when they were through

at their time here at this University they felt that they had a successful academic, intellectual and personal

experience. That to me was what mattered most. {25:00.4}

It seems to me that with the caliber of student we bring to this University, if we do things right, a student

will, on average, graduate in four years. Certainly 70 percent of them will. 30 percent of them will not.

Maybe because a few of them will decide to leave the University, or maybe because some of them decide

to stay longer to pursue other sorts of academic interests. But it doesn’t seem out of bounds to imagine the

idea that you would be able to graduate 70 percent of our students in four years. The question is, how do

you go about doing that? I’m going to show you a few slides to give you some idea of what we’ve been

doing over the first few years with respect to those students. But I want to start by giving you a sense of

how we’re trying to frame things for our students.

If you’ll indulge me I want to show you about a two-minute video. This video was shown at Orientation

this last summer to the class of 2017. Now already I’m sort of framing things in a different way than we’ve

talked about before. In much the same way that students went off to high school and were told that they

were going to graduate in four years, and so you just did the math, and it was four years later, and that’s

when you knew your class was. Well, we’ve decided to start doing that here. There is, in fact, for every

single class its very own logo, its very own champion, its very own sort of identity as that particular class.

So as we, and Carolyn here, help start this up, as we bring students onto campus for Orientation, the

opportunity to have it impressed upon them that graduating in four years is something that makes sense is

one of the things that they see. Let’s go ahead and see the video. [video plays] {0:29:29.1}

One of the things about that video that impresses me is that those are all undergraduates doing the work. I

remember when I went to college it didn’t look like that. I sat in a lot of classes and listened to a lot of

people that looked like you and me talk at me. I took some tests and I graduated four years later. It really is

remarkable the kinds of students who show up on this campus, and the sorts of things that we are

innovating to make a new way of learning available to them. I’m going to briefly go through some of the

things that we’re working on and if you have questions, I’d be happy to answer them.

First, let’s start with finding the right kind of student to come to the University. It’s interesting, we’re one

of those universities that is enormously attractive to students, and at the same time, there are restrictions on

how it is we’re supposed to go about the application and admissions process. So the top 10 Percent Law

requires that 75 percent of our students automatically qualify to come to the University. At the same time,

we have this ever-increasing population of applicants who want to be here as well. So for that other 25

percent it becomes, in many ways, as competitive as going to an Ivy League school. So there’s this

confluence of these two very different sorts of processes by which we admit our students. And it’s from

within that that we’re supposed to form the four-year 70 percent graduation class. If we’re smart about it,

we will go in and look at these students and we will start to evaluate them in the context of graduating in

four years. The first thing I want to show you is a new way that we’re doing this, and I don’t want to take

credit for it because this is not my doing, this is Dan Slesnick, senior vice provost in the provost’s office,

who worked with a team to help develop a way for us to actually evaluate a student’s success on this

campus specifically in the context of graduating in four years. You can imagine what a lot of these

parameters are that define success. They might be the fact that they have a high SAT score, or that they

have taken a lot of dual credit or AP credit courses. But there are lots of other factors that come into play as

well, and they end up helping us decide who the students are that we’re going to try to recruit. We do this

in a couple of ways. First, we have some amount of discretionary financial aid available to us and we use

that money to go after students that we think are going to be most successful in graduating in four years.

That’s the equivalent of going after your very best students and having a merit process for that. {32:04.5}

The other thing we want to do look at our students who come here and identify the ones who are going be

to be challenged with respect to graduating in four years, so we can see what we can do to supplement their

educational experience to help them to be successful. Notice this is happening within this parameter that we

5

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

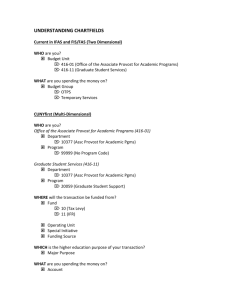

have described as ‘the four-year graduation rate.’ I’m not sure how well you can see this data, I tried to

keep the numbers as small as possible here, as few as possible so that you can see them, but this is showing

you something of the correlations between the SAT that students have coming to the University and their

predicted four-year graduation rate. Without going into too much detail, just to give you an idea of the

difference between 2012 and 2013 in terms of our recruiting, when we tried to incentivize students coming

to this University, we incentivized towards students who were more likely to be successful. You can see

that with respect to some of the traditional parameters. You see that the 2013 class is measurably better

than the 2012 class, whether it’s the fact that we have a higher percentage of students with high SATs

coming to the University, or the fact that they have a greater likelihood of graduating in four years, and that

we’ve reduced the number of students with a lower likelihood of graduating in four years. That might not

seem like that’s all that unusual, that correlation between SAT and four-year graduation rate, but then you

see how it’s complicated, and this is one of the challenges we face at this University.

Take a look at this data right here. This shows you students coming into The University of Texas by college.

And this shows you the likelihood of graduating in those colleges. This right here, actually for me, is some

of the most depressing data you can imagine. It shows that the students who are defined as our best students

by SAT, the students coming in engineering with really impressive average SAT [scores], are least likely to

graduate in four years, and similar trends are seen in natural sciences. The reasons for this are many. These

are more difficult degrees, they’re more complicated, they have tougher courses, and, I think, most

importantly, for a lot of these students they don’t really know that this is the kind of major that they want to

have. On the other hand, you see that we have some colleges that are already achieving substantial

success—communications, for example, has already made its four-year mark. But at least having this kind

of data available to us lets us know who the students are that we have to go after if we’re going to help

them improve their ability to graduate in four years.

So what are we doing? It comes in stages. The first stage is with respect to college readiness. We want to

make sure that before the student matriculates, before they arrive on campus for Gone To Texas and start in

class, that certain things have happened. One is that they get oriented. Marc Musick did a wonderful job

over the last couple of years of overhauling orientation so that it became an expectation that every student

would go. In fact, last year more than 99 percent of our students showed up for orientation and got what I

think is a much more academically focused experience. We’ve also started to implement more substantial

science, technology, engineering and mathematics readiness for our students. These are the students who

typically struggle, and these are the students for whom a lot of front-end college readiness work was done.

Notice for example, a Summer Bridge Program that we put into place. We identified about 200 students

who were least likely to be successful at UT and were able to give them $6000 scholarships to show up to

UT in the summer, to take a math course, to take a writing course in the second summer session and to

incentivize their participation by giving them $1000 if they passed their courses. The argument here was

that these students would have been at home in the summer working, so why not have them come here and

do the work of doing well in their coursework to be successful? {36:05.5}

Once they get on campus though, it’s entirely possible that they will not be successful. We need to be much

more nimble in the way that we work with our students. We implemented a Major Switch Program. This is

an interesting idea that said perhaps there are students, especially in a STEM field, who get a month into

school and suddenly realize that they’ve made a terrible mistake, that they weren’t as ready as they thought.

They take their calculus course, they take their chemistry course, and they’re failing them, and failing them

badly. In the old days, what would happen is they would continue to fail the courses all the way up until the

end of the fall semester, and they would basically go on dismissal or probation, and it would be very

difficult for them to recover. These days, with the Major Switch Program, we’re actually able to identify

those students, sit down with them, talk to them about what their goals are, and if their interest is in getting

better and staying in the sciences, we help them. Most recently, about forty students chose to leave. They

were routed into non-majors math and sciences courses, so they’ll still get their core courses taken care of,

but they’ll be able to move over into a new field of study and not be burdened by the bad grades that they

might get in those other courses.

If you take a look at the four-year graduation rate likelihood of success, you’ll see that about a quarter of

our students will struggle to make the 40 percent four-year graduation rate. For any student who has less

6

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

than a 40 percent likelihood of graduating in four years, we require that they be part of a success program.

There are a variety of great success programs that have been created around the campus in engineering,

undergraduate studies, DDCE and natural sciences. These programs provide students with mentoring, small

classroom experiences and supplemental instruction that allows them to perform better in terms of what it

is they’re trying to accomplish in their freshman year. We substantially increased the amount of money we

put into these programs, as it shows you right here. We have about 1,200 of our students who are now in

success programs in their freshman year. We’ve also decided to expand the idea of a small community

experience to all of our students—that’s 7,200 incoming students, putting them into 20 student cohorts,

means 360 connections, 360 different small cohort experiences. We did that this year for the first time with

the help of undergraduate studies and the folks working in the FIG program, and then in all of the

community programs across campus, and the honors programs and the success programs. This was really a

remarkable effort. When I first came to UT twenty-five years ago, the idea that a student would have a

small classroom experience was a bit of a fiction. Now, we can honestly say that every single student who

shows up here as a freshman sits in a room around the table with twenty other students, with a mentor, with

an instructor, and has a conversation once a week. This didn’t come overnight – this came from about two

decades of building up the kind of infrastructure to make this happen. And then, importantly, as I said, we

provided an identity for these students, the fact that they are part of the class of 2017. That right there is the

logo for the class of 2017. There will be a class of 2018 logo, 19 logo and so on. These students met on the

football field at the beginning of the year and formed a giant picture of the shape of Texas as I recall and

started to build that identity. Student government, senate, all of the campus leadership has rallied together

around these students to help them understand that this is part of their responsibility. So you ask, how has

this worked?

Any measure of UT success with its freshman is something we can be hugely proud of. President Faulkner,

about two decades ago, recognized that we had very bad freshman year persistence. We were down in the

high 70 percents compared to our peers. These days, we are easily over 90 percent freshman persistence. In

fact, this last year, even with the largest class in UT’s history, we had almost 95 percent of our students

persist into the next year, which is an all-time record for the University. So I think we can honestly say that

we can be really, really proud of what we do for our freshmen. The question is what we’re going to do for

our juniors, our sophomores and our seniors as they continue on here at UT. This is where I’m turning a lot

of my work now. We have incentive-based programs through financial aid where we’re trying to not get

students to show up here because they got money, but rather, receive money because of their

accomplishments while they’ve been here. You saw an example of this with the Summer Bridge Program,

where we had 200 students pass math and science courses. Maybe because they wanted to pass them, but

certainly the $1000 that they got when they finished didn’t hurt. Another example of incentive programs for

our students is the University leadership network, a program for students with need. They come in, 500 of

them, as freshmen, and for the next four years they will receive $5000 in scholarships as part of a

leadership program training, mentoring and community service as they start to grow into roles with the

University. To be able to do this, they have to stay on track to graduate in four years, and they have to

continue to develop as students within the program. There are $1500 enrichment programs for Presidential

Achievement Scholars that let them do experiential learning. There’s the Academic Excellence

Scholarships for the freshmen students in the success programs, if they stay on track to graduate in four

years. So these are ways in which we provide money to students, but the money is provided as a

consequence of the behaviors they exhibit towards graduating in four years. I should impress on you the

idea that this is not money that is anything other than discretionary. This is over and above what the

students might have received from financial aid otherwise, and it’s money that we can use to incent their

behavior.

Two other things to mention, and then I’ll open the floor for questions. This is a big University, and I

would imagine that 99.9 percent of what takes place here is well-intentioned. But, at large universities that

are well-intentioned, lots of things fall through the cracks, lots of miscommunication. All you have to do is

go onto student websites, go onto their parent’s websites, and you hear about how it is that somehow

somebody has done their kid wrong, or that somebody has done them (the student) wrong with respect to

advising, with respect to coursework, especially as it applied for four-year graduation. If you talk to the

faculty, if you talk to the deans of the colleges, they will all say, “you know, if the student’s on track to

graduate in four years, they will graduate in four years, we can promise this.” But if you talk to the students,

7

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

they will oftentimes tell you a different story. I think one of the important functions of my office is going to

be to serve in that sort of support role for making sure those lines of communication are established

between the student and the colleges. Every year, having looked at the data, we see there are three or four

hundred students who should graduate in a particular semester, and then they just do not. The question is,

what happened? Why didn’t they graduate? If you stop and talk to them and get their feedback, you hear

lots and lots of stories about how they were denied this and they were denied that. Well, I’ve been around

long enough to know that very often that’s not the real reason behind what was going on. But I also know

that if you encourage these students to be aware that there are other resources available to them to be

successful in graduating we need to make sure this happens, so we can help to eliminate the excuses that

people might have about being able to graduate.

As you saw in that video, we have a way of reminding students about graduation. This is an evolving tool

in the registrar’s office that allows students to see how they’re doing with respect to four-year graduation.

This is going to be of enormous benefit to the advisors, so that they can look at it with a student and say,

well you know it’s not 50 or 60 different really complicated degree requirements anymore, it’s just the

color. You need to do something if you find yourself down in the yellow about turning around and getting

those extra courses so that you can graduate.

The final slide I want to show you is the way in which I hope that you will be able to help this University

with respect to four-year graduation. On the left hand side is Shelby Stanfield with the registrar’s picture of

how our degree audit system looks. That’s a collection of if-then-else statements that shows you how

complicated our degrees are. On the right is a model for what our peer institutions look like. You’ll notice

that they are substantially less complicated. I think all of us agree that our degree plans have over the years,

in a very well-meaning way, gotten more and more, I guess a nice word for it is…sophisticated. That

sophistication though, can oftentimes be a stranglehold on a student’s ability to graduate. So there’s effort

taking place across the various colleges to look at trying to remove some of those lines connecting those

bubbles and in fact, to pop some of those bubbles so that our students will be able to get the quality

education they need, but not necessarily have to jump through quite as many hoops. So, there’s a lot of

work taking place in CUDPR, and a lot of work taking place with the colleges on these sorts of initiatives.

That’s the end of my presentation. I would be happy to take any questions that you have. {46:15.0}

Sonia Seeman (associate professor, music):

Hi, I’m Sonia Seeman in the Butler School of Music. I appreciated your prefacing this in terms of the

quality of education. I have two questions, one specific and one general that address this emphasis on the

four-year program. One, the specific question has to do with summer programs. In certain schools the

amount of funding available for offering courses over the summer are being whittled. So I’m wondering

how that initiative as one way in which students can finish within four years is going to be offset with the

availability of courses over the summer when tuitions are going up, fewer students are enrolling, and there

are a smaller number of programs are now being offered in the summer? My other question has to do with

if a four-year degree can be balanced with the issue of students who do creative or important double major

emphases, which can take an additional year. What would be unfortunate is if those students that choose to

have double majors in biology and music, for instance, if these students are made to feel like somehow they

are failing, when in fact, they are going to be graduating with powerful contributions to society. Whether

this system as devised could support students that may take longer, either because they’re double majors or

first-generation students from disenfranchised minority communities that have not had access to training.

Laude:

With respect to the second question, the easy answer is to say we’re only trying to do it for 70 percent so

the other 30 percent can take more time if they would like. On a certain level that is true. I think that if you

look at a typical population of students you will find that there are those who want to be more creative in

the way they use the time they spend on their undergraduate education. I’ve talked to no one in positions of

authority that are seeking to stop that. I think we have remarkable students who are capable of thinking of

ingenious ways to weave these sorts of ideas together. I don’t think that there’s necessarily going to be any

pressure that way. I do think that when we think more broadly about what education is going to be as we

change the way semester credit hours are earned as students start to show up on campus with substantial

amounts of credit already earned, we’re going to think about what that time on campus ought to look like.

8

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

Should a student who’s trying to double major in biology and music necessarily be spending their time

trying to knock off a variety of different three-hour semester credit, three-semester credit hour courses,

when in fact, what they’re trying to do should be something more substantial than that. I think the jury’s

still out on how that’s going to evolve. But at this particular point I don’t think there’s any issue or concern

about whether or not students are going to be forced to stay here for four years before graduation.

With respect to financial aid, I agree with you completely, the idea that we would be incentivizing students

to take financial aid in the fifth year, while at the same time building up student loan debt makes no sense if,

as alternative, we can find more creative ways to move the students into summer school. I’ve been working

with Tom Melecki on this particularly. He’s the director of the office of student financial aid. We’re going

to look at specific examples of programs where if students come in the summer, either it’s because this is

where they’re going to be able to get that rare laboratory that they wouldn’t be able to get otherwise, or

where they need that remediation you talked about, that we actually provide the financial aid for it so that

they’re doing it in the summer, rather than finding themselves doing it in an expensive fifth year. {50:44.1}

McClelland:

Hi, Blinda McClelland, biology. It’s my understanding that Texas A&M offers a financial incentive at the

end of four years for completing their degrees in four years, whereas your incentives all seem to be on the

front-end of the four-year experience. I was wondering if that had been a consideration, to offer the carrot

at the end of four years rather than at the beginning.

Laude:

Well, I think that the carrots we’re using here are along the way. Certainly you can imagine the one simple

way to get students to graduate is to dangle expensive carrots in front of them after four years. I think we’re

taking a more nuanced approach here, in which we put the emphasis on the quality of the educational

experience along the way. Things like the University Leadership Network provide $500 to the student at

the beginning of every month for four years. But this is conditioned upon them actually staying on track to

graduate. I think most of these are “evaluate as you go” ways of doing things.

Brian Evans (professor, electrical and computer engineering):

Brian Evans, engineering. There are a number of integrated MS/BS programs or BS/MS programs.

Computer science has one, for example, so the student would finish and get a bachelor’s degree at the end

of five years along with a master’s degree. They wouldn’t make the four-year cut. There’s also plan II in

liberal arts and engineering. We’re about in my department to do integrated BS again, with possibly about

20 percent of students finishing at the end of five years. These are really among our very best students that

are ready for grad school. Strictly speaking, none of those are going to get counted as finishing in four

years.

Laude:

Well, this is one of the challenges. If a student, as things are currently structured, comes in as a first-time

freshman the clock starts on him. If they’re a student for example, in an architectural program in which it

takes five years to graduate, or one of these combined MS programs, then that counts against us. We also

have students who leave and go into pharmacy after two years and that counts against us. At some point I

think we’re going to have to be more sophisticated in the way we evaluate success for students. In fact, we

can think more broadly about this. Our students go about the business of gathering credit from multiple

institutions. You see a lot of institutions with very low numbers with respect to graduation rates. But in fact,

students started there but ended up graduating somewhere else and they didn’t get credit for the fact that the

student did this. We’re currently tied to this idea of the first-time freshman, but I think that exploration of

this with the coordinating board and others is going to be important.

Evans:

I completely agree. So you talked about having the 30 percent headroom. We don’t have that headroom,

because even if we keep 90 percent every year, even 95 percent, by the time we get to the fourth year you

take point 9-5 times point 9-5, times point 9-5, you don’t have a lot of headroom to make 70 percent. And

9

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

so we don’t have a lot of…. if 70 percent is our goal, which is an, ad hoc, informal, target from which I

understand, it’s hard to get that goal with all of our five year initiatives that are out there. {54:10.1}

Laude:

I think what has to be appreciated is that higher education’s changing pretty substantially in a variety of

ways. Things like the combined degree you just talked about, the opportunity for students to earn credit

more fluidly through high school and through online initiatives means that the traditional notion of a fouryear graduation rate is going to start to dissolve away.

Anthony Petrosino (associate professor, curriculum and instruction):

Tony Petrosino, college of education. I realize you might not be in a position to answer this question now,

but if you could, provide us with a little bit of the computational models that are being used to make these

predictions on the recruiting of students that it seems like we’re doing to address the 70 percent graduation

rate. In other words, I applaud all the efforts that are being done on campus for the existing students that we

have, the incentive programs, etc., I’m perhaps a little concerned on what predictive models we’re using to

actively recruit students who would somehow raise our four-year average. For instance, if I say fees are

being used then I know there’s a high correlation with income and education level. That might be intended

or unintended consequences affecting the general student body. If you want to maybe comment on one or

the other, I’m particularly interested in the computer model or what factors we are using in the model that

predicts whether students are going to have a 70 percent or….

Laude:

Sure, sure. I would prefer not to talk about the specifics of the model other than to acknowledge exactly

what you’ve said. The reality is that there are certain types of students who are more likely to graduate in

four years, and it doesn’t take a lot to sort that out. They come from affluence basically, and that affluence

buys that student lots of advantages with respect to ultimately being successful. So then you start to ask

yourself what the purpose of a public university is supposed to be? Is it a university that goes after the best

of the best students and is able to demonstrate rather effortlessly that they were able to graduate them in

four years? Or does it do everything it can on behalf of students coming from underserved backgrounds? I

think that this University has performed admirably this way. Regardless of what you think of the top 10

percent legislation, it delivers a substantial population of students to this University who in fact,

demonstrate based upon those predictive models that they are unlikely to be successful. However, having

said that, I would put our success programs on this campus whether it’s TIP, whether it’s Gateway, whether

it’s the Discovery Scholars program, the work being done into engineering, and then these new programs

that we’re trotting out. These are specifically intended for that population of student. Whether it’s to

supplement their academic experience or to incentivize with financial opportunities, this is the way that

we’re going to try to raise that particular group up. To sum it up, if it works, then that kind of student who

was predicted to graduate with less than a 40 percent likelihood will now be above that bar and there will

be no such thing as that kind of student. All of them will be graduating up here.

{57:41.9}

Hans Hofmann (associate professor, integrative biology):

Hans Hofmann, integrative biology. So David, I’ve found this very interesting what you have said but there

are two things, and one you just mentioned, that you didn’t say anything about. I’m curious whether there is

any thinking in this direction. One is, is there any chance to get rid of, I may be a minority here on this

view, the 10 percent law, to modify it, to make it less of a straightjacket? And the other question is, because

that could obviously help with it though….and the other question is, in other states at public universities

there are arrangements that students who do not do well as freshmen at the flagship University then get

encouraged to a lesser campus and vice versa, it doesn’t seem to happen here in Texas very much, is that an

idea that is worth thinking about or am I discriminatory?

Laude:

So I sit with Kedra Ishop [vice provost and director of admissions] a couple times a week, and we talk

about how absolutely fascinating the state of Texas is in which to execute the business of higher education.

In response to both of your comments, these are things that are outside our control. We deal the hand that’s

been given us. I think having said that, that, when I look at the kinds of students who show up on this

10

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

campus, I teach a 500 student section chemistry course every fall and spring, and the kids are just so good

compared to twenty years ago. Anybody who thinks they were better twenty years ago just hasn’t spent

time with these students. It’s just remarkable, we keep raising the expectation bar for these students and

coming from all walks of life, they’re stepping up. Granted, there are those who struggle, but on the whole

the entire ship is being raised. I’m not particularly concerned about the quality of student we get, they’re

doing great when they show up here, and I think we have a responsibility to all of the students across

whatever sort of foundation or background they come from.

Hofmann:

Thank you.

Linda Reichl (professor, physics):

Linda Reichl, physics. There seems to be a huge contradiction between what the administration is doing

and your talk, because there was…the first person who asked questions asked about the fact that resources

to teach summer courses are being cut, and I know that’s true in natural sciences. There will be much fewer

courses taught next summer than there have ever been in the past because there are no resources available.

Can you comment on that?

Laude:

I think it’s safe to say that there is an appropriate tension that exists between the student side of things and

the resource side of things. And, it’s a good thing to have that tension because that’s how you build

efficiencies. I think as we start to move in a direction that puts more importance on the summer, you will

naturally see a willingness to move in that direction. The money that I talked about providing was student

financial aid, so the students would be able to take courses in the summer. If we’re able to demonstrate that

taking courses in the summer will get students graduated in four years, then I think that the provost’s office

will certainly work with the colleges in making sure that those courses are offered.

Reichl:

Okay. And when, when will that happen? Because it’s not happening in the near future. So we really do

have a contradiction.

Laude: {1:01:17.7}

So it’s not so much a contradiction. It’s the realization that the University, particularly in the STEM areas,

finds itself awash with students who need to be able to graduate. And certainly until such time as we get

enrollment management sorted out with respect to putting students where they need to go, we’re going to

have to put resources where they need to go for us to be able to get these students graduated. The

commitment that I talked about, about making sure that students would be able to graduate in four years if

they’re making normative progress, is one that I would stand by. So, if a college wants to come back to the

provost’s office and say ‘we don’t have the resources to be able to do that,’ they should, and then we will

work together to make this happen. You know, when I came into the provost’s office a summer and a half

ago, we had just admitted the largest class of students in the history of the University, and the provost’s

office immediately allocated substantial amounts of one-time money to make sure that the introductory

courses were taught and to make sure that the students would be taken care of. I have to assume that that is

going to continue to be the process.

Evans:

There are two things. One is our TA, at least in engineering. Our TA budgets have been cut year after year

for eleven years in a row. I don’t know about the others, it doesn’t sound good elsewhere. The other thing

with the…..you can put a lot of money in the first year cohort that comes in, but if they’re going to be

around for four years you need four years of additional funding and we just haven’t seen it. Where I am.

Laude:

Coming at it from the student’s side, I know exactly what you’re talking about. The challenges in terms of

making the first year a good one will pale compared to the challenges of what we need to do to find the

resources to provide for the students finding their courses so they can graduate. This is something that has

to be an absolute priority for the University.

11

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

[woman’s voice: Thank you.] Thank you. [applause]

Hart:

Thank you, David. We’re now going to hear a report from our faculty ombudsperson, Mary Steinhardt,

who is also a professor in kinesiology and health education. She gives us a report every year. Welcome

Mary.

Mary Steinhardt, professor, kinesiology and health education; faculty ombudsperson, faculty

council:

Thanks everyone, thanks for having me. I wanted to tell you that although I’m going to talk about the

faculty ombuds office that there are three ombuds offices on campus, and if you Google ombuds you’ll see

the white thing on the left and we have a student ombuds office that’s run mainly by students. Brittany

Linton is a PhD student in educational psychology and there are other students working in that office. We

have a full-time staff ombuds, and that’s Jen Sims, located in Walter Webb Hall, and then the faculty

ombuds, that’s me. So the faculty ombuds office was established in 2004 to provide faculty with a prompt

and professional way to resolve concerns, conflicts and complaints beyond coming to their supervisors, and

then in 2010 we also started to see postdocs. The faculty ombuds office is located next to the post office in

the west mall building. It’s the same office that the faculty council is located in and Debbie Roberts helps

run that office, and, as you know, is fabulous.

This is the general trend from 2004 when the faculty ombuds office was created. It shows the visitors and

you can see from the first four years average visitors was forty-three. That’s gone up. This past year I saw

ninety-four people. In 2010, when we started seeing postdocs there were two postdocs, the next year three

post docs, and this past year six postdocs. Of the ninety-four people that came by this past year, they were

from twelve different colleges, forty different departments and divisions, as I said, six postdocs, six

lecturers or specialists, eighteen assistant professors, seventeen associate professors, and thirty-one full

professors. Thirteen department chairs or directors and three deans, about equal numbers of males and

females.

As you might expect, the postdocs had concerns mainly linked to their mentors and their relationship with

their mentor. Lecturers were concerned about their contract being renewed or the teaching load. Assistant

professors were concerned about tenure, that continues to be the main thing that they come for. Associate

professors promotion, and full professors post-tenure review or retirement. Other than just across the board

faculty conflicts, thirteen people just requested information. I’m working about ten to fifteen hours a week.

Most cases can be resolved without filing a formal grievance, and I really enjoy this job because I have

extraordinary cooperation from everybody. I’m really grateful for the deans and chairs and Renee Wallace

has been fabulous. The UT lawyers are fabulous, it helps me do my job better.

When a faculty member first comes to me I tell them to read the website and then I tell them we have four

principles: confidentiality, neutrality, informality, and independence. First and foremost I tell them that

their visit is confidential and I won’t discuss their concerns unless they give me permission. Although there

are exceptions to that and we go over those, mainly eminent risk for harm. I’m a neutral third party, so I

don’t take sides but I try to help everybody. It’s informal and off the record. I only write things down to

help me remember and when we close the folder I destroy the file. Nobody has to come to the ombuds

office, it’s voluntary and it’s independent and I report directly to provost Fenves. The student ombuds and

the staff ombuds report to the president. {1:07:33.2}

This is just a list of ways that ombuds can help. This is for all three offices. For myself, mainly I’ve learned

to value listening more than I first did. This is my sixth year in the ombuds office, so I do a lot of listening.

I answer questions, or if I can’t or don’t know the answer I find out the answer. I explain a lot of policies

and procedures or I if don’t know the answer I find out. I mainly work to help people identify options and

next steps they would take and so forth, and this is posted up on the website and you can read it more. But

this is the way we all work. When people come in, we try to identify the issue, I try to get a picture for

what’s the issue and what do you want to happen? Then we strategize all the options we can think of

together and what’s the possible outcome for each option and what option would be best to help them get

what they want. And we try to facilitate understanding and resolution to their issue.

12

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

This is a list of concerns commonly brought to all the ombuds offices. For the faculty ombuds it’s mainly

tenure and tenure related issues, post tenure review, and retirement issues, but these more broadly are the

amount of issues we had. And then, I love this from Stan Roux, he used to show this to me all the time, and

I agree this is basically what I do. I remind people to choose actions that best demonstrate fairness and

respect, and where appropriate, advocacy for rewards. Nonetheless, conflicts will arise. Well meaning,

bright people sometimes disagree and most can be resolved amicably. I’m happy to answer any questions

that you have. I’m not as popular as Dave Laude. [applause]

Hart:

Thank you Mary very much. She is remarkable. She’s great at her job, I can tell you. And so we move on to

the report by the faculty welfare, the chair of the faculty welfare committee, Blinda McClellan from

biology to report on an idea for a faculty education benefit. Blinda.

McClelland:

Thanks Hillary. Thank y’all. Do I….how do I? Okay. We’re working on some initiatives, some little baby

steps to improve faculty welfare in as economically efficient way as possible. So we’re looking at initiative

to improve our lives here, our work lives as well as our personal lives, without costing a whole lot of

money. One of the ways that could be identified that could be improved would be to offer educational

benefits to faculty members. So to enable faculty members like the staff can do now, and this may be

something that y’all are not aware of but staff are permitted, and I’m sure encouraged in some ways to take

up to 3 hours of course credit here at the University and essentially have a tuition waiver for that privilege.

So they can essentially take one course a semester. What we are suggesting is that we extend that to faculty

members as well. I have the website up here for information regarding the staff educational benefits so this

is just a little bit of information right from their website. There are of course, restrictions that apply to this

staff educational benefit. It doesn’t cover several things, and so we would assume that should this privilege

and benefit be extended to faculty members there would also be some kind of restrictions involved.

Obviously the restrictions go on for two pages. All right, three! {1:11:54.2}

Okay, so among the questions that you might have are ‘why would someone with a PhD want to take some

kind of education here at The University of Texas?’ Well, I just sat down and thought of several ways…

reasons why you might want to take courses at the University, and I actually came up with a nice long list,

starting with a biologist like me and ending with a biologist but trying to hit all the different areas and

colleges on campus. For instance, I do, I might do…my colleagues and I do lots of research in Latin

American countries, so why wouldn’t I want to take a course in Spanish? Something like that, it’s a very

simple example. Career development, we have very rapidly advancing fields, I know mine is

extremely…biology is very rapidly advancing. Emphasis on interdisciplinary studies, this is something that

I think the Center for Teaching and Learning is emphasizing to us that we should broaden our perspectives

and increase qualifications for grant awards. If you have to turn in some of your qualifications to a grant

proposal agency this might be to your advantage. Increased facility and data analysis and communication,

my taking Spanish might fall under that category. Retention and recruitment of faculty, I don’t have any

solid data, I don’t think there is any solid data regarding how many people might refuse to come to The

University of Texas or stay at The University of Texas without this benefit, but UT is very much lacking in

this benefit to faculty when compared to peer institutions.

I’m about to show you some data. Personal development, there probably as many reasons for y’all to want

to take a course as there are y’all in this room. All right, so…facts, evidence, data, information. I’m a

biologist. I am the worst kind of biologist, I study animal behavior, which makes me squishy, even within

the context of biology, and Hans can verify that. So Physics Cat and my colleagues notwithstanding, I tried

to find some facts, evidence, data and information about faculty educational benefits. So I set about to look

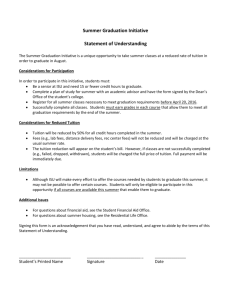

at the ten largest public university campuses by enrollment as of fall 2012. Here’s the deal: first of all,

every university I contacted, either by the website or calling them up, which was an adventure, make no

distinction between staff and faculty when it comes to educational benefits. So these are our peer

institutions as far as enrollment is concerned and I’ve offset The University of Texas. We’re number five,

right behind College Station, which is the only university that’s worse in offering some kind of benefit. I

13

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

called them up and I speak Aggie, but it took like five transfers and my explanation what a benefit was

initially to even get them started to understand what I was talking about and lack of evidence is not proof of

absence, or something like that. I had to verify and they said ‘oh no we don’t offer that.’ So anyway, our

peer institutions enrollment-wise, every one of them offers staff and faculty benefits. Not only that but for

the most part, the faculty benefits and staff benefits include: spouses, domestic partners and children and

there’s an incredible variation. Arizona State, for instance, offers nine semester hours per semester of

benefit for both staff and faculty and their families. We’re not just a little behind the curve, we’re way

behind the curve when it comes to educational benefits. So what we are proposing is taking little baby steps

to first just extend the benefit that is enjoyed by staff to faculty and then maybe at a later time we can work

on extending this as our peer institutions have done to family members as well.

Here are our peer institutions from the top national public universities. This is not by enrollment, this is by

whatever the US News and World Report algorithm is for overall awesomeness, and, the ten here are, it’s

fairly stable, which ten universities…so this is our competition, right? These ten universities end up in the

top ten. Although if you look from year to year they change positions so I didn’t put actual numbers for

ranking. The University of Texas at Austin is in a three way grudge match for 16 th place. But once again,

these are the universities that we are competing with, and you can see that staff educational benefits and

faculty educational benefits across the board are offered by all of our peer institutions that we might be

competing with for faculty recruitment and retention.

Can we predict how many faculty would take advantage of this benefit? Well, no, in fact it took five phone

calls and four e-mails to get information, a ball park figure from the accounts receivable department to find

out approximately how many staff members are taking advantage of this benefit right now this semester,

and they gave me the ball park figure of about 220. So doing the math, I figured out that this is

approximately 1 percent of the staff, so extending that to faculty this would be about 25 people. So, another

question might be what is the cost and I put cost in air quotes because, basically one of the criteria we

would assume would be part of the restrictions on this benefit would be only if there are open slots in a

class so we certainly, of course, want our students to graduate in four years. We certainly don’t want to

bump somebody out of a course in computer science if it’s going to prevent them from taking that class. So

basically this is kind of a benefit that would be provided on a stand by basis.

So, cost? It’s an empty seat in a classroom and it’s paperwork. So I’m not really sure we can equate this

kind of benefit with what a student would be required to pay to take those three hours, but UT tuition for

three hours ranges from a low in liberal arts $2,059 to $3,066 in the business school. But one of the

restrictions that you see if you look at the staff restrictions is that basically business school courses are not

permitted within this benefit. {1:19:38.1}

So this is my presentation and it’s my understanding from Hillary that I’m presenting this information to

you as chair of the faculty welfare committee. We are working on some other initiatives. I’m kind of in a

fact-gathering mode right now, and if anybody has any questions, Hillary has said that I just need to get the

flavor….

Hart:

Yes, this is Hillary. Hillary Hart, civil engineering. No, I just suggested a report, and if any of you have

ideas for this, have objections to this, you’re telling Blinda is helpful. I think she would plan to bring some

legislation, probably in January. Anybody have any comments?

Charters Wynn, associate professor, history:

I think it would be really wonderful if that was extended to retired faculty because that’s, you can really…

McClelland:

Yes, and, many schools that I looked into do, and thank you, offer this to, not just to retired faculty, not just

to retired staff but to alumni. There are...one of the universities you pay $25 and you can get, you know, so

it’s a real marginal fee to cover the paperwork. But it’s like flying stand by. If an airplane door closes and

there’s an empty seat it’s gone. And so in this sense, having an empty seat in the classroom would be I

think, a terrific benefit for many of us at marginal, if not zero cost. Yes.

14

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

Domino Perez, associate professor, English:

Domino Perez, department of English. My understanding of this benefit as it extends to and as it relates to

staff is that it is for staff who are non-degree seeking. Well, there are two options, there is a non-degree

seeking version and then there is a degree-seeking version. [McClelland: hmm.] And then there is a

specific amount, there’s a specific number of hours that the non-degree seeking [McClelland: right.] staff

members can take. Do you imagine instituting these kinds of tracks for faculty? Is there a degree that’s

going to be involved? I mean, how are you imagining outcome?

McClelland:

Well, that’s entirely possible. I mean, I’m assuming the vast majority of us in here have terminal degrees,

which are PhDs, so again, why would you want to take a course if it’s not really going to benefit you

towards a goal? I guess the answer is most of us…. I do see the possibility of achieving let’s say a master’s

degree in something, although it might not, if you’re already a professor here, it’s probably not going to

benefit you in terms of getting another job. But for instance, if you’re applying to a funding agency it might

look good on your transcript. Another thing about the staff benefit is that I think it’s too restrictive. In many

cases, they don’t extend it to graduate level classes. In other words, the benefit does not apply to any

dissertation courses and certainly there are restrictions on the business school. [Perez: and the number of

courses you can take. The other thing I want to…] Exactly. It’s three hours. You can take multiple courses

as long the number doesn’t exceed three hours per semester, which, by the way, is also very behind the

curve for our peer institutions. {1:23:44.7}

Perez:

The other thing that I would suggest is that there are national programs that faculty can apply to that allow

for, I don’t want to say….. euphemistically, retraining or additional training in another area in their

particular field. So if I’m a Victorianist, I can apply for a grant to receive additional training in digital

media. That kind of certification [McClelland: right.] or retraining program might be something that you

want to think about also as a possible outcome.

McClelland:

Yeah, I think that, I think it’s great and, people brought up what about online courses? Why don’t you just

take an online course? Well, I think none of us would really equate an online course or a workshop or

something like that with taking an actual course. So it’s great—I was just surprised to find out how limited

The University of Texas’ offerings to faculty along these lines are compared to our peer institutions.

[Perez: Thank you.] [Hart: one more question.]

Jon Olson (associate professor, petroleum and geosystems engineering):

Jon Olson, petroleum engineering. Just a quick question. As it’s currently implemented at UT, is there any

restriction in grade? Does it have to be credit or no credit? Does it have to be for a grade only? I don’t

know if there’s…[McClelland: you know, I’m not sure.] okay.

McClelland:

I’m not sure. I assume that if they sign up, they take it for a grade. I haven’t actually discovered one of

these 220 people that is taking….. thanks Hillary, thank you everybody. If you have any additional

questions or suggestions, not just about this but any other aspect of faculty welfare that you think we can

work on this semester please contact me. {1:25:33.3}

Hart:

Thank you Blinda. Thank you. [applause] So we may have some legislation in January. All right, the last

item on our agenda is a resolution, a new resolution that was posted this morning. Some of you may have

had a chance to read it but you certainly had a chance to read the print version that was available at the

table outside. If anybody has not gotten a copy of the resolution, Debbie I’m sure there…just, just wave

your hand and Debbie will give you one. Resolution to stop the implementation of Shared Services is

presented by Dana Cloud in communication studies and Snehal Shingvahey…Shingavi, English, but this is

Dana. Dana’s the presenter. Solo presenter.

15

December 9, 2013 Faculty Council Meeting

Dana Cloud (associate professor, communication studies):

Thank you. I want to thank Hillary and also Debbie Roberts for allowing us to be on the agenda today, and

I want to thank you all for hanging in there. It’s late, I know. I think it’s really important to get this

conversation started among faculty about Shared Services and what it might mean to us. The resolution as

it stands is mainly designed today to get the conversation started. Any voting or discussion of amendments

and stuff can happen later, in the New Year. As far as getting the conversation started, we wanted the

faculty to know the reason we have serious questions and concerns about implementation of the Shared

Services plan. You can find out a lot more information about it in all kinds of different places but you may

be familiar that it’s a plan to centralize some of the services at the University.

Some of the concerns that we have, well, first we should all say that we agree that we are all interested in

delivering a high quality education, supporting faculty and students. I think a thing that the faculty should

really, really, really be concerned about is the displacement of staff dedicated to local units, so that your

administrators, your person who handles your travel budgeting, your person who deals with your money,

your equipment for your lab, your IT professionals who are just down the hall, these kinds of things are I

think, at risk. Not everywhere, not universally, but it’s very difficult to know to what extent that’s true. I

think that could be incredibly damaging to our work lives and, at The University of Michigan where the

faculty stood up against this same plan, although theirs is ten times smaller than ours, note the