Time and Change

advertisement

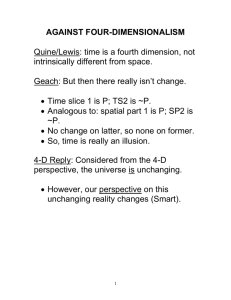

Time and Change Consider where we left off. According to our naive descriptions of properties, we say the following: a is F What about time and change? Change can be represented in the following way: a is F at t1 a is not-F at t2 Or, in the following way: a was F a is F [but] a will be not-F Presentism: • Only those things that exist at the present time – now – really exist at all. • The only qualities that these things really possess are the qualities that they possess now. • In other words, to say “a is F now” is really to say “a is F”. • And so, computers exist; dinosaurs do not exist (≈ are not real?); Mars outposts do not exist (≈ are not real?) Eternalism: • All things exist. Or, rather: past and future objects and times are just as real as currently existing ones. • Reality is a four-dimensional spatiotemporal manifold of objects and events: “the block universe.” Consider the following: Tensed statements: It is now raining It was the case that there existed dinosaurs I will one day visit Greece Non-tensed statements: It is raining on 24 October 2006 World War I occurred after the American Civil War There existed dinosaurs before Columbus landed in America McTaggart (1908) calls tensed temporal judgments “Ajudgments”, and tenseless temporal judgments “B-judgments”. A-judgments typically change in truth-value. B-judgments are permanent. Question: Are tensed statements reducible to tenseless statements? One view: A-judgment tokens are reducible to B-judgments; that is, there can be tenseless truth conditions. E.g. o: “It is now raining” (at t) Tenseless truth-condition: o is true iff it is raining at t. On the other hand, A-theorists tend to be anti-reductionists and hold that “now” etc. are fundamental features of reality and that the A-theory captures the idea that time flows. B-theorist: static theory of time. “A-theory of time”: presentism + anti-reductionism “B-theory of time”: eternalism + reductionism The problem of persistence Perdurantism: Objects persist through time in virtue of having successive temporal parts; so only a part of a persisting object, its current temporal part, is present at any one time during its existence. Endurantism: objects persist through time in virtue of being wholly present at every time at which they exist, i.e. endurantism entails the denial of temporal parts. Possible combinations (live options marked by ‘*’): presentism + endurantism* presentism + perdurantism [advocated by a school of Buddhism] eternalism + endurantism eternalism + perdurantism* Chisholm, “Identity through Time” 1. The Ship of Theseus Consider the philosophical puzzles of the ship of Theseus and the carriages of Socrates and Plato. “These puzzles about the persistence of objects through periods of time have their analogues for the extension of objects through places in space.” (274a) Consider the river example. Butler: It is only in a ‘loose and popular sense’ that we may speak of the persistence of such familiar things as ships, etc. But persons can be said to persist in a strict and philosophical sense. 2. Playing Loose with the ‘Is’ of Identity What kind of looseness? “A is B” said in a loose sense, if we use it in such a way that it is consistent with “A has a certain property that B does not have”. Five types of misuse (275-77): “is” is avoided. fission and fusion title talk type vs. token feigning identity 3. An Interpretation of Bishop Butler’s Theses On the one hand, familiar things are ‘fictions’, logical constructions or entia per alio. (277b) On the other hand, persons persist ‘in a strict and philosophical sense’. Persons are not just fictions. So, if a person exists at one place, P, at t1 and at another place, Q, at t2, then we may infer that the thing existing at P at t1 is identical to the thing existing at Q at t2. 4. Feigning Identity Consider a simple being, a table: Mon Tue Wed AB BC CD “Although AB, BC and CD are three different things, they all constitute the same table.” This is what Hume called the ‘succession of objects’. (278a) [Skipping lots of subtle points…] “But if there are entia per alio, then there are also entia per se.” (281b)