Report - Pacific Analytics

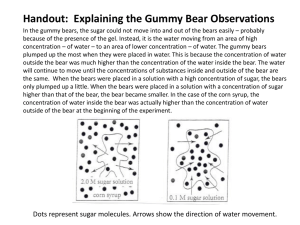

advertisement