FHRS Case Study: Wales 1 Summary

advertisement

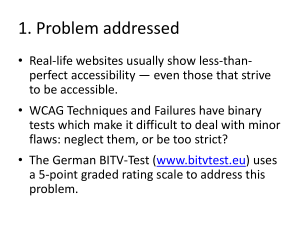

FHRS Case Study: Wales 1 This mini report presents findings from one of 8 local authority case studies developed for the stage 2 process evaluation of the Food Hygiene Rating Scheme (FHRS) and the Food Hygiene Information Scheme (FHIS). The report provides evidence from discussions with a local authority food safety officer, food business operators and consumers. The 8 case studies are aggregated within the main report of process evaluation findings, which included additional data sources, and are intended to provide snapshot illustrations of how the schemes were perceived and experienced by individuals within a local context. Summary In this Welsh urban local authority, FHRS has been incorporated into the regular inspection programme yet, after two years, not all businesses had been assigned an FHRS rating due to limited staff resource. Though inspections have not changed under FHRS, food safety officers were taking more time scoring and discussing ratings. This was to ensure ratings were justified and to maintain consistency in scoring; however, inconsistencies were noted between local authorities. Extra administration and formal requests (re-inspections and appeals) have added to workloads. Overall, the local authority officer said that levels of broad compliance have improved as ratings of ‘3’ and higher were observed to be increasing. Yet it was noted there remains a hard core of food businesses where improvements remain difficult. Language and cultural issues were thought to act as barriers to change. Relationships with some poor performing food businesses have been strained. Interviewed food businesses felt extra pressure under FHRS, particularly in light of the fact that display of ratings would become a legal requirement. The requirement to document food safety systems was considered arduous for small business owners and the level of downgrading for incomplete documentation of food safety systems was considered unfair. Food business operators acknowledged that mandatory display of ratings would draw customers’ attention to food hygiene and were anxious that low ratings would deter new trade, although they relied heavily on regular customers. In the focus groups, consumers were very positive about the FHRS but felt more information about the scheme and wider publicity were needed, including mandatory display of ratings on business premises. Food hygiene information was considered more useful when people took time to review different eating choices such as for a special occasion or when on holiday. 1 The local authority context The urban local authority is characterised with a population of over 300,000 according to the 2011 census. 16% of residents live in the most deprived areas of Wales and the 9% unemployment rate is higher than the Welsh average. Health, retail and education are the largest industries and the area is also popular with tourists. At 14%, the ethnic minority community is three times the Welsh average. The local authority had a food hygiene scheme in operation before FHRS was launched in late 2010. According to December 2012 ratings data (supplied by the FSA), one in four (24%) food businesses in the area had been given an FHRS rating or 0, 1 or 2. Research sample One local authority food safety officer was interviewed by telephone which took place in March 2013. The officer worked in a team of 15 inspectors which covered over 3000 food businesses within scope of the FHRS. For research with the other stakeholder groups, the officer helped to identify a neighbourhood with a concentration of poor performing food businesses. A main inner-city road was selected for fieldwork with food businesses. The area was comprised mostly of eating establishments serving ethnic cuisine. Businesses were closely packed in mostly older (100-200+ years) buildings. At one end of the road there were a number of empty shops. Very few FHRS stickers were visible at street level and these showed only 4 or 5 ratings. Fieldwork with food business took place over two weekdays in May 2013. Nine food business operators took part in the interviews which took place on their premises during business hours. The study aimed to collect the perspectives of mainly low rated food businesses: six proprietors had been given an FHRS rating of less than ‘3’. The sample comprised mainly takeaways along with a pub, restaurant and a retail shop. Seven were independently run businesses while the remaining two were franchises. Eight people took part in the focus group – 4 males and 4 females – which was hosted in a local hotel conference room. The focus group was conducted on a weekday evening in May 2013. Participants had been selected to ensure awareness of the FHRS and interest in new eating experiences and/or concern for food hygiene. In the screening exercise, 7 reported they had seen FHRS stickers displayed on food premises, 2 had used the FSA ratings website and 3 said that FHRS ratings had influenced their choice when eating out. 2 Local authority viewpoint The local authority food safety officer viewed the FHRS as a good thing for Wales and said the scheme acts as a tool to motivate food businesses to improve standards and to gauge progress. The respondent noted that levels of broad compliance have improved in the local authority as ratings of ‘3’ and higher were increasing. Operations Applying a gradual approach to rating food businesses under the FHRS, the food safety team have carried out inspections according to the food business risk rating. The respondent reported that all A-C category businesses had been rated (except for new businesses).1 The food safety team have been unable to rate all food businesses due to limited resources. Changes attributed to the FHRS Under FHRS, the team was applying the same inspection programme as they had done previously. There had been no change to the length or inspection visits but local authority officers were taking more care assigning ratings and more time discussing scores with other team members. It was felt the FHRS requires more paperwork to justify ratings. The team have administrative support to help with printing stickers/certificates and uploading ratings to the website. Extra time to discuss scores and administration of the scheme have added to team workloads. The respondent mentioned that the E. coli cross-contamination guidance had also added changes that required more care in scoring compliance with food hygiene law. The local authority officer reported that the FHRS has changed relationships with food businesses somewhat. The scheme can act as a motivator for proprietors by providing a structure for improvements, but it could also be interpreted as giving the local authority more control over proprietors. Sometimes food business operators reacted negatively to low ratings. The respondent added that this reaction was being exacerbated by negative media coverage and freedom of information requests to uncover poor performing premises. Rating consistency, training and guidance Consistency was not an issue within the food safety team. They continued to address this through multiple means: team meetings and one-to-ones between food safety officers and managers; consistency training across Welsh local authorities; and discussions at regional technical meetings. 1 The frequency of food hygiene interventions is determined by the assessed risk of food premises, assigned as categories A through E, with A being the highest risk. 3 The respondent reported that cross-Wales training has revealed inconsistencies between local authorities and suggested that consistency training needs to be ongoing to be effective and to ensure that scoring across local authorities is comparable. The Brand Standard was considered to be a useful source of guidance on scoring consistency. However, it was felt that it needs to be updated in relation to the E. coli cross-contamination guidance. Safeguard measures The local authority officer reported that formal requests from food businesses have added to workloads, described as ‘a pressure point’. Since the start of the scheme, the respondent estimated there have been about 150 rescores; there were five appeals in 2012 and no complaints or rights to reply. These formal communications tended to come from food businesses with ratings less than ‘3’. But it was noted that some of these were initiated by institutions (e.g., nurseries) that were broadly compliant (rated 3 or 4) and the respondent was concerned that these cases were taking resource away from the lower performing premises. The respondent also expressed concern that the volume of formal requests and appeals will increase when it becomes mandatory for food businesses to display ratings. This will require more staff resource which could be partly offset if fees for re-inspections are invested in food safety team resources. Views on food business engagement The local authority officer had noticed improvements in food business awareness of the FHRS and in attitudes about the importance of food hygiene. However, there is a hard core of food businesses that will not change until they are forced to display their ratings to the public. Difficulties were associated with food business operators from a minority ethnic background where there are language and cultural issues with understanding the concepts in the FHRS. These was also a high turnover of ownership in deprived areas of the city. Together, this made it difficult for some poor performing food businesses to improve. Feedback from businesses (following food hygiene training) suggested that proprietors wish to be informed of developments in food hygiene requirements before inspections. To address this, the local authority had started advising new businesses about documenting food hygiene systems prior to the first inspection. With support from FSA funding, the food safety team had also been paying one-toone advisory visits to 0 and 1 rated businesses to help them improve their hygiene standards. 4 Display of ratings The respondent observed that there was a reluctance among food businesses to display FHRS ratings – with those rated 4 or 5 more likely to display in order to promote their hygiene standards to customers. It was felt that officers have ‘no teeth’ when discussing display with poor performing food businesses. Therefore they ‘do not go out of their way’ to encourage display with this group. The local authority officer felt that mandatory display will help generate changes needed among poor performing food businesses. However, it was anticipated this requirement will entail more work for the team with more businesses exercising their safeguard rights. Scheme publicity FSA campaigns in Wales have raised public awareness of food hygiene information – there have been more freedom of information requests, contact from special interest groups, and local media attention. Local authority publicity was concentrated at launch of the scheme in late 2010 and early 2011. Food businesses Overall views The FHRS was received with a mix of views from food business operators. From a positive perspective, the scheme was seen as a measure to keep businesses ‘on their toes’ as the extra work was for the benefit of public safety. On the other hand, business operators felt the requirements of the scheme (particularly the documentation of food safety systems) were difficult for small business owners. There was also the view that the FHRS was not being implemented properly as those with poor standards of hygiene were able to ‘hide from the public’ because they were not displaying their rating. Views on ratings received In the sample, food business operators with a ‘4’ or ‘5’ rating were generally pleased and felt the outcome reflected their hard work. Those with a rating of less than ‘4’ were unhappy with the outcome, mainly because they expected a higher rating or because they felt the rating was unjustified. Several businesses had been marked down due to poor documentation of food safety systems. For example, the owner of a Turkish restaurant and takeaway (rated 3) said he was told everything was fine except his ‘paperwork’. It was unclear to him why the local authority removed 2 points for this. He was proud of his business and did not feel a ‘3’ was good enough to display. Yet he worked 12 hour days with little help and could not do the level of record keeping required. All respondents with a rating less than ‘5’ indicated they wanted to improve further. 5 Barriers to changes Issues that made it difficult for proprietors to introduce requested changes included: time constraints on small business owners; planning permission and landlord restrictions. There was also evidence that operators did not fully understand the changes required or what could be done to improve their hygiene rating, particularly among those whose first language was not English. Safeguard measures Respondents in the sample were aware of their safeguard rights. Three were waiting for a requested re-inspection and one was planning to apply closer to November 2013 when it would be mandatory to display ratings. An owner of a grocery shop and butchery (with a 3 rating) felt that six months was too long to wait for a re-inspection. A pub manager that had been uprated from a 2 to a 5 rating after re-inspection was pleased with the process. Requested structural changes had been completed by the owner of the pub franchise. Display of ratings/results Only those businesses with a 4 or 5 rating were displaying their rating. These businesses were proud of the outcome and felt that the rating was a way of letting their customers know that they treat food safety seriously. Those not displaying did not wish to publicise their rating because it was ‘not good enough’ – this sentiment was also felt by businesses with a ‘3’ rating. Other reasons for not displaying were that the proprietor had misplaced the sticker/certificate and the concern that a low rating would have a negative impact on business. Food business operators had received a letter from the local authority informing them that display of FHRS ratings would be a legal requirement in November 2013 and they generally supported the measure. It was felt that mandatory display was needed to fully implement the scheme. An owner of a pizza franchise (who was displaying a 5 rating) reasoned that not until display is mandatory and people know more about the FHRS will ratings make a difference to businesses. Those with lower ratings who weren’t displaying were anxious to achieve a higher rating before November. There was concern that the local authority would not have the resources to re-inspect businesses before this deadline so proprietors would be forced to display a rating that did not reflect the changes made. In addition, the owner of an Indian restaurant (who was displaying a 5 rating) was concerned that if other Indian restaurants display 1 or 2 ratings British people will come to distrust all Indian restaurants and consequently his business will suffer. 6 Awareness of other food business ratings Proprietors were mainly aware of local business ratings from the stickers on display. Two respondents (both with 5 ratings) had researched ratings of area businesses on the FSA website because they wanted to know more about their competition. One noted that they would feel humiliated if their rating was more than a point lower than a competitor. Views on FHRS impact Respondents generally did not feel the public were engaged with the FHRS because the value of good quality food outweighed food hygiene ratings. But it was acknowledged that mandatory display of ratings would draw attention to food hygiene. Concerns and suggestions for improvements There was a common view that the local businesses were not being adequately supported by the local authority. All but one respondent in the sample were from an ethnic minority background. Business owners felt they were being ‘targeted’ and their livelihood was under threat. It was suggested that they should be consulted and better informed by the local authority prior to introducing new food safety requirements. There was also a view that the FHRS was not being applied consistently across countries. For example, a manager of a pub franchise was aware of procedures in another franchise located in England and felt that the ratings given were not comparable. Consumers Role of food hygiene when eating out Focus group participants agreed that people tend to take hygiene for granted when eating out – cleanliness was less noticeable than uncleanliness. As one person described it, ‘I eat with my eyes'. People liked to see the food being prepared and relied mainly on visual cues for signs of uncleanliness (e.g., ‘If it’s not clean on the front, it’s not going to be clean on the inside.’). The group agreed that certain places have higher hygiene standards (food chains) than others (ethnic food eateries). Therefore, food hygiene was a consideration when a lack of hygiene was evident but other criteria were also important when eating outside the home, such as value for money, food quality, and convenience of location. 7 Experience of FHRS All focus group participants were aware of the scheme and commented that stickers/certificates are increasingly visible in food establishments (e.g., local shops, chain takeaways, sandwich shops, cafes and restaurants). Only the higher ratings (4 and 5) had been noticed. One female participant said her boyfriend uses the FSA mobile app when deciding where they will eat out. One male had seen the FHRS mentioned in a television programme and others had seen negative media attention about businesses that have been forced to shut down due to poor hygiene. No one was aware of any FSA or council promotion of the FHRS. Applying FHRS ratings If food hygiene information was more readily available focus group participants said they would start to compare ratings across similar businesses when deciding where to eat. People reported they would avoid those businesses rated 2 or lower and said that businesses that do not display ratings when most others do would be treated with suspicion. To focus group participants, a zero rating meant ‘no hygiene’ and it seemed counter intuitive that a zero FHRS rating meant the food business was still operating within acceptable standards. Minimum standards There was general consensus that a ‘3’ rating was the minimum acceptable standard. A rating of 2 or below was associated with a higher risk of becoming ill. Ratings in different circumstances People in the focus group identified different eating circumstances in which hygiene standards may vary along with other priorities like convenience, familiarity, food quality and price. As a general rule, people expected a higher level of hygiene (at least a 4 rating) when they were paying more for a meal such as for a special occasion or at an expensive restaurant, for example, ‘that should be your right because you are paying for that right’. The composition of the eating party did not seem to alter expectations for the minimum standard of hygiene. Parents with younger children indicated that speed of service and price were important considerations. Food hygiene information was considered more useful when choosing a new place to eat or in unfamiliar territory, like on holiday. These were also instances when people relied on ‘word of mouth’ or online reviews. Generally, more information was useful when people take time to decide on where to eat, for example, ‘I’d be willing to find out more if I was going to an eating-in place rather than a takeaway. A takeaway, I haven't got time for all this.’ (female, age 35-49) 8 Extra information was considered less useful for regular eating places when the reliability of food quality and convenience were prioritised, as one person commented, ‘If it’s somewhere you go all the time, you become a bit blasé about it and I’ve been fine every time I’ve been there. So you just go there without thinking. If it’s somewhere new you might look into it more.’ (male, age 35-49) However, when faced with the proposition that a regular eatery had a low (0-2) rating, people said they would either stop going or would think twice before going and perhaps get more information on why the rating was low. In contrast, people were less forgiving about an unfamiliar place that had a low rating. Everyone said they would not even consider it. Eating out to satisfy a yen for ‘greasy’ foods and ethnic cuisine was another occasion when food hygiene standards were relaxed. This type of eating tended to be connected with familiar territory and alcohol consumption, as one person explained, ‘You tend to stick with places that you know and you trust. I’d be very wary really of going to a completely new kebab place or somewhere like that, even when I was drunk.’ (male, age 25-34) Feedback and suggestions for improvements All participants viewed the FHRS as a good idea and became more engaged with the scheme as they learned more about it. It was unanimously decided that the scheme would be more effective if all food businesses displayed their rating and if there was more done to promote the use of the scheme. People questioned how mandatory display would be enforced. Participants wanted further information on the interpretation of ratings and what exactly the weaknesses of individual businesses were. It was felt that this extra information could be provided on the FSA/council website. They also questioned how frequently food businesses were inspected as this was important for the accuracy of the ratings and how much trust they could put in to the scheme. 9