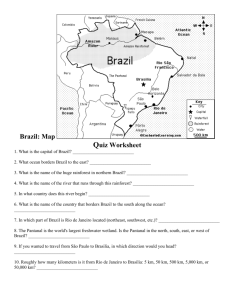

Core – Brazil v 1.0.0 - Open Evidence Project

advertisement