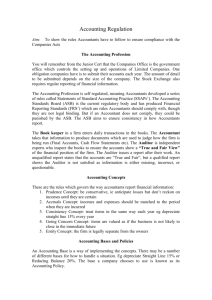

Accountants demand and supply paper 2014

advertisement