Caroline Bond Nov 2011

advertisement

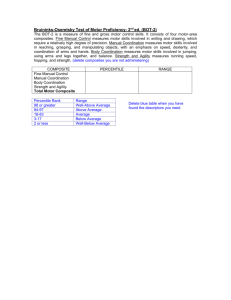

An initial referral for a child with a statement for dyspraxia and attention difficulties in a primary school Lack of assessment and intervention materials for schools Small OT team and long wait for OT input Specialist teachers and EPs keen to develop materials to address this need Education project group formed with consultation from OT team - Whole School approach comprising: Primary school audit tool Resources for classroom staff A targeted motor skills (Wave 2) intervention comprising KS1 and KS2 assessment tools An intervention planning booklet Half day training for SENCo and TA pairs and follow on practitioners workshops The programme consists of: The MMSA assessment The MMSP targeted intervention It is for: Children who show signs of gross motor, fine motor or organisational difficulties Children with a medical diagnosis e.g CP only included after discussion with an OT The teacher checklist is designed to help select children to participate and actively involves teachers in observation and assessment What do schools need? An assessment that focuses on relevant skills, is quick to complete and informs intervention and assessment of progress What form should an assessment of children’s motor skills take? Strongest evidence is for cognitive-motor approach to assessment of motor skills (Wilson, 2005) The best evidenced motor skill norms were used (Crawford et al 2001) where possible Tools were developed and revised over a year with OTs, teachers and TAs Inter-rater reliability testing with 37 children in 11 schools found high levels of agreement between researchers and TAs (Bond, C., Cole, M., Crook, H., Fletcher, J., Lucanz, J. & Noble, J. (2007). The development of the Manchester Motor Skills Assessment (MMSA) – An initial evaluation. Educational Psychology in Practice, 23(4), 363-379) The process of drafting and re-drafting has lead to: KS1 and KS2 assessment tools focusing on functional skills relevant to the school context (gross, fine motor skills and organisational skills) The assessment is designed to be done before the child takes part in a motor skills group and at the end Children are assessed individually on 10 tasks and each assessment takes approximately 15 minutes For each item the child is rated on a four point scale, which follows a skill acquisition model 0 = Not able to complete task 1 = Early stage of skill acquisition 2 = Becoming more competent 3 = Fluent Scoring descriptors provide extra detail to enable accurate scoring The assessment helps to: (a) show progress (b) help with programme planning A DVD has been developed to support training Training DVD example Maximum score is 30 Generally 15-18 would be maximum score for a child with global difficulties to participate in the group Where a child has specific difficulties in one area the score profile, teacher information and knowledge of group profile used to decide whether the child would benefit from being in the group Use individual profiles and knowledge of the children to identify who will work well together in a group Use profiles to identify key areas for individual children to work on Balance the range of activities in the session to suit broad needs of the group e.g. more fine motor or organisational tasks Developed in response to research and school need for: Intervention programmes with a built in assessment component Intervention that could be delivered by school staff Evidence based motor skills programmes Programmes linked to theory of motor skill learning and development Ideally have 2 adults running sessions initially Group size: 4 children if 1 adult, or 6 if 2 adults Run sessions daily for 20 minutes 8 weeks or 3-4 sessions per week for 12 weeks Structure (Ripley, 2001) Whole group warm up Paired activities 3x 2 minutes (mix of fine and gross with individual target setting) Collaborative group cool down activity End of session – review, rewards Emphasis is upon the group being a positive, fun experience to boost confidence A cooperative approach with frequent opportunities for working together and building relationships Activities are repeated over 5 sessions to enable children to build fluency Children’s target setting and tracking sheets enable them to see their own progress Overall structure (Ripley, 2001) Cognitive motor approach (Wright and Sugden, 1998; Sugden and Chambers, 2005) Visualisation strategies (Wilson et al. 2002) Mastery experiences (Bandura, 1994) Active problem solving (Mandich, Polatajko, Missiuna & Miller, 2001) Frequent practise (Sugden & Chambers, 2005) Praise and reward to boost performance (Crust, 2005) Once children have completed a block of sessions they are reassessed and a decision made whether they would benefit from a further block (some progress) or referral on (no or ltd progress) Children given a break between blocks and class teachers encouraged to work on some specific areas in order to generalise skills Some schools have found it useful to run KS1 one term then KS2 the next Repeated measures design with 24 children assessed using the MMSA Pre -------------- T2 ------- T3 -------------- T4 6months Intervention 6 months Monthly progress 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 T1 Effect sizes T2 0.010 0.603 T3 T4 0.023 Development project finished in 2008. All 39 schools that had been part of project surveyed in 2009 with 59% response rate 60% continuing to deliver the motor skills intervention School level impact was variable External support from the team was rated highly More support requested re handwriting interventions Training has been revised and continues to be available to schools Feedback has lead to shift of focus to sustainability and whole school approach Both the whole school and targeted elements may be published as the Manchester Motor Skills Assessment and Intervention Package Continued research is needed to build the evidence base in relation to the effectiveness of the intervention, to develop the assessment tool and develop a parent involvement element Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In Ramachaudran, V. S. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of human behaviour (Vol. 4, 71-81). New York: Academic Press. Bond, C., Cole, M., Crook, H., Fletcher, J., Lucanz, J. & Noble, J. (2007). The development of the Manchester Motor Skills Assessment (MMSA) – An initial evaluation. Educational Psychology in Practice, 23(4), 363-379. Bond, C. (2011) Supporting children with motor skills difficulties: An initial evaluation of the Manchester Motor Skills Programme. Educational Psychology in Practice, 27(2), 143-153. Bond, C. (in press) Developing provision for children with motor skill difficulties: the role of EPs. Educational Psychology in Practice. Crawford et al (2001) Identifying Developmental Coordination Disorder: Consistency between tests in Missiuna, C. (ed) Children with developmental coordination disorder:strategies for success. Hawthorn Press:London. Crust, L. (2005). Imagery: Mental drills for physical people: how recreating all-sensory experiences can profoundly affect your performance. In Walker, I. (Ed.), Sports Psychology: the will to win, 11-25. London: Peak Performance. Mandich, A. D., Polatajko, H.J., Missiuna, C. & Miller, L.T. (2001). Cognitive strategies and motor performance in children with developemental coordination disorder. In Missiuna, C. (Ed.). Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder: Strategies for Success, 125-143. New York: Hawthorn Press. Ripley, K. (2001). Inclusion for children with dyspraxia/DCD: A handbook for teachers. London: David Fulton Publishers. Sugden, D. & Chambers, M. (Eds.). (2005). Children with developmental coordination disorder. London: Whurr. Wilson, P. H (2005) Practitioner Review: Approaches to assessment and treatment of children with DCD: an evaluative review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 46:8 pp 806-823. Wright, H. & Sugden, D. E. (1998). School based intervention programme for children with developmental coordination disorder. European Journal of Physical Education, 3, 35-50