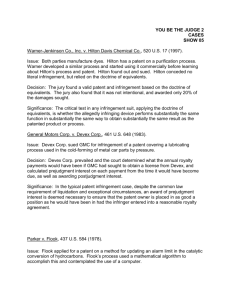

FCBA-Model-Patent-Jury-Instructions-UPDATED

advertisement