England and Scotland in the 17th century

advertisement

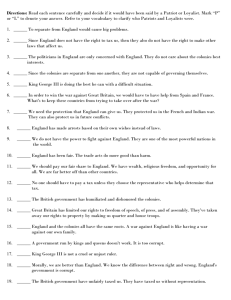

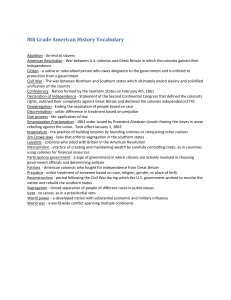

England and Scotland in the 17th century A) regional difference B) religion C) revolution 1688 D) Act of Union Developments in Ireland George III. and the American revolution A) domestic politics B) colonial unrest Act of union with Ireland Rise of GB in 18th century A) Society B) Politics British colonial expansion A) first British Empire B) wars Revolution and War A) French revolution B) Napoleonic Wars Industrialization and Progress A) The impact of Industrialization B) Political reforms A union of England and Scotland seemed unlikely at the beginning of the 17th century. The two nations had been periodically at war with each other for almost 700 years as a result of disputes over control of border regions and occasional attempts by the English to expand northward into Scotland. In order to protect its independence, Scotland maintained a traditional alliance with France, England’s primary enemy on the European continent. When Elizabeth I of England died childless in 1603, James VI of Scotland, a member of the royal house of Stuart and a relative of Elizabeth, inherited the English throne. In addition to ruling as James VI of Scotland, he now became James I of England Regional Differences Scotland James held royal authority in two kingdoms that were very different: Scotland was: sparsely populated its land was largely barren and infertile. Rocky soil, a cold and wet climate, and insufficient irrigation prevented agriculture from thriving. A long tradition of self-sufficient farms and estates discouraged trade and limited the growth of industry. Scotland was divided into two distinct regions, the Highlands and Lowlands. By far the largest concentration of population in Scotland was in the southern Lowlands around the two principal cities: Glasgow and the capital city, Edinburgh. The Lowlands were fully integrated into royal government; the king ruled with little opposition. Scotland’s Parliament met rarely and dealt with limited issues. In the Highlands, however, the royal government had little direct influence. Clans—social groups based on extended family ties—still dominated the region. England In contrast, England at the beginning of the 17th century was a dynamic society, growing rapidly in population and wealth. England’s south and east had fertile agricultural land. In the north and west, estates carried out sheep herding on a large scale. A thriving export trade existed in wool, grain, and other products. England’s capital city, London, was one of the largest cities in the world. The Tudor monarchs, who ruled England from 1485 to 1603, had effectively centralized English government by the early 17th century. The nobility—the once powerful class of landowning aristocrats—no longer formed a powerful independent political force, but instead served the Crown and became dependent on royal support. The gentry—landowners with country estates— formed the core of royal government in the countryside, enforcing the law as sheriffs or serving as justices in the local courts. Although the Tudors centralized administration, they failed to implement a financial system to pay for the escalating costs of government. Rents on royal lands, supplemented by limited taxes on imports and on the church, barely financed government administration. During wars or times of emergency, the monarchy had to request funds from Parliament, which alone had the right to approve additional taxes and to pass new laws Religious Differences Religious issues also separated the two nations. Both the Church of Scotland and the Church of England were Protestant churches. However, in England the monarch reigned as head of a compliant, centralized church. Henry VIII had established the Church of England in 1534 with the monarch as its supreme head. His successors maintained tight royal control over church affairs and held the final say in matters of religion. John Knox preached a form of Protestantism to the people of 16th-century Scotland. Later called Presbyterianism, this religion became a symbol of Scottish nationalism. Church leaders strongly resisted efforts by Scottish monarchs to establish control over the church. James had less control over Scotland’s church. Protestantism had made major gains among the people, and a Presbyterian system, built upon independent local church organizations, formed without royal approval. In 1560 the Scottish Parliament accepted the Presbyterian form of Protestantism as the official religion. James appointed bishops to establish his authority over the church, but the Presbyterian system remained intact on the local level and continued to decide many religious matters independently of the king and the bishops. Revolution of 1688 Protestant political leaders launched a revolt against James II. The Revolution of 1688 deposed James in favour of his nephew, William of Orange. William was a Dutch Protestant noble who had married James’s daughter Mary. An act of Parliament made Mary II and William III joint monarchs in 1689. The revolution deeply divided the Scots. As the head of Scotland’s royal family, James II continued to attract loyalty, especially in the Highlands. The most powerful Scottish politicians and aristocrats were willing to accept William III only if he gave Scotland greater freedom to govern itself. William granted the Scots a nearly independent Parliament and pledged not to interfere in the Scottish church. William later made several overtures for a political union, offering the Scots the benefits of free trade with England, participation in the emerging English Empire, and guarantees to preserve Scotland’s legal, religious, and political institutions. The Scots rejected these proposals. The Act of Union William and Mary were childless, as was Mary’s sister, Anne, who succeeded to the throne in 1702. To assure a smooth transition of power to a Protestant monarch, in 1701 the English Parliament passed the Act of Settlement, which stated that a German branch of the royal family, the Hannovers, would succeed Anne as the monarchs of England. The Scottish Parliament refused to ratify the act, creating the potential that the two kingdoms would split after more than 100 years under the same monarchs. Queen Anne Anne, queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland, based much of her administration on the advice of her ministers. Anne had no children, and her ministers, fearful that Scotland might ally with the French following her death, pressured the Scottish Parliament into agreeing to merge the two nations into a single kingdom. The English feared that an independent Scotland might ally itself with France and provide a backdoor for a French invasion of England. The English fear of an invasion was especially strong at the beginning of the 18th century. At this time, England led a coalition of nations that were struggling to prevent Louis XIV of France from gaining mastery over Europe. After 1701 the stakes increased as Louis attempted to establish his grandson on the throne of Spain. The ensuing War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) engulfed most of western Europe as England, The Netherlands, Denmark, Austria, and later Portugal formed an alliance against France and Spain. To avoid facing an enemy on the northern border, Anne’s ministers threatened the Scottish Parliament. They warned Scotland that they would treat all Scots as aliens in England, stop all trade between the nations, and capture or sink Scottish ships that traded with France. These threats led the Scots to accept the union with England. In 1707 Great Britain was born. Fear had led the politicians of both nations to a union that would prove durable for hundreds of years. The Act of Union of 1707 created a single national administration, removed trade barriers between the countries, standardized taxation throughout the island, and created a single Parliament. However, England and Scotland continued to have separate traditions of law and separate official churches. Developments in Ireland Catholics had gained hope of a return to power in Ireland during the reign of James II, who appointed Catholics to positions of authority in the royal administration and the military hierarchy of the island. Following the Revolution of 1688, James II fled to Ireland, where he raised an army of Catholic supporters. William III defeated the Catholics and once again imposed the firm rule of Protestant nobles. Although Ireland had its own Parliament, which was composed of Protestant landowners, the real power lay with royal officials, who administered the island based on orders from London. The Protestant rulers of Ireland instituted a series of highly restrictive laws that excluded Catholics from owning land or firearms, from practicing certain professions, and from holding public office. These discriminatory laws united Ireland’s Catholic population in opposition to Protestant. Rise of Great Britain Great Britain emerged from the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) as one of the world’s great military powers. Traditionally a naval power, Britain had built a modern, professional army during the reign of William III. This army, under the brilliant military leadership of John Churchill, 1st duke of Marlborough, led the anti-French alliance to decisive victories. On the seas, the British navy captured the island of Minorca in the Mediterranean and the strategic fortress of Gibraltar, which guards the entrance to the Mediterranean, on the southern coast of Spain. These victories gave Britain control over the Mediterranean. In 1713 and 1714 a series of treaties known as the Peace of Utrecht brought the war to a formal conclusion. As a result of the war, Britain gained Gibraltar and important trade concessions from Spain, including a monopoly on the slave trade to the Spanish colonies. From the French they won the colonies of Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Hudson Bay John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough John Churchill, known as Marlborough, was one of England’s greatest military commanders 18th-Century Britain British society was stratified in the 18th century, with a tiny aristocracy and landed gentry at the top and a vast mass of poor at the bottom. For the aristocracy, the 18th century was its greatest age. British lords who controlled large estates saw their wealth increase from a boom in agricultural production, an expansion of investment opportunities, and the domination of the government by the aristocracy. They built vast palaces and developed new areas of London, Edinburgh, and Dublin. The monarchy almost exclusively appointed aristocrats to the most important political offices. Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, England, was designed in 1705 by British architects Sir John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor. Blenheim is an example of the stately mansions constructed during the 18th century by England’s increasingly wealthy aristocracy. In contrast to the aristocracy, the gentry lost much of the political and financial influence it had wielded since the days of the Tudor monarchs. Many holders of small estates found that land was no longer the secure source of wealth it had once been, especially with the high taxes imposed on landowners to finance Britain’s wars. The immense estates of Britain’s aristocratic class provided their owners with a constant flow of funds, while higher taxes often consumed the profits generated by the smaller estates of the gentry. Although the gentry’s status in the local community was secure, merchants who traded luxury commodities overseas soon eclipsed the gentry in wealth and influence on the national level during the 18th century. Society in the 18th century was becoming more fluid than in the past, in part because of the growth of the middle classes in towns and cities. Middle-class families earned their livings in trade or in professions, such as law and medicine. They valued literacy, thrift, and education, ideas that were spread by thinkers of the Age of Enlightenment. Especially influential were philosophers John Locke and David Hume and economist Adam Smith. Locke and Hume stressed the importance of the senses and the environment in shaping the individual. Locke also described the human mind as a blank slate that was to be filled by education and experience. Smith, in his book The Wealth of Nations (1776), demonstrated how the efficient organization of economic activity created wealth. Increased literacy and education spread throughout the country. In towns, the middle classes established lending libraries to distribute books, clubs to discuss ideas, and coffeehouses to debate politics. Newspapers became the most popular form of media, and more than 50 towns produced their own newspapers by the end of the century.. The newest form of literature was the novel. Pamela; or Virtue Rewarded (1740) by Samuel Richardson was one of the first works of this genre. The writings of novelist Jane Austen were popular toward the end of the century. The rise of the middle class was also seen in the most important religious movement of the era, Methodism. Founded by theologian John Wesley, Methodism encouraged the population at large to believe personal salvation could be achieved without relying on the formal rituals of the Church of England. Wesley directed his energies to labourers and the poor, but his message was derived from the attitudes of the middle class. Poverty dominated the lower reaches of British society, especially as the population grew and food prices rose in the middle of the century. Towns swarmed with homeless families, the sick, and individuals with disabilities. The government and charitable organizations established orphanages and hospitals, as well as workhouses where the unemployed could find temporary work. While women and children were left to live in poverty, the government forced able-bodied men into military service by the thousands. London experienced the worst of this situation. Poor migrants flooded the city seeking work or charity; most found an early death instead. Paradoxically, improvements in sanitation, medicine, and food production allowed many poor people to live longer lives, increasing the population of poor and adding to the problems. The epidemics of plague and smallpox, which had routinely killed a third of the people in towns during earlier centuries, were now a thing of the past. The production of cheap alcoholic beverages, such as gin and rum, eased some of the pain of the poor, but increased alcohol consumption also raised the level of violence and crime. Crime was so common in 18th-century Britain that Parliament made more than 200 offences punishable by death. Executions were weekly spectacles. To deal with excess prison populations, the British government deported many inmates to British overseas colonies. The government sent tens of thousands of convicts to the Americas as indentured servants and established the colony of Australia as a prison colony at the end of the century. Penal Colony The Port Arthur penal settlement in Australia was in service from 1830 to the 1870s. The high-security colony housed 2000 prisoners at a time and was known for its harsh discipline. It was restored in 1979 and today is a popular tourist destination. 18th-Century British Politics Following the union with Scotland, the British government functioned according to an unwritten constitution put in place after the Revolution of 1688. This agreement between the monarchs and Parliament provided for the succession of Anne’s German Protestant cousin, George of Hannover, and his heirs. It excluded from the throne the Catholic descendants of James II who now lived in France and who periodically attempted to regain the throne. Their supporters were known as Jacobites, and they rose in an unsuccessful rebellion in 1715. The Church of England remained the official religious establishment, but most Protestants who belonged to other churches enjoyed toleration. The revolution also resolved the struggle for power between the monarch and Parliament, which had been an ongoing issue under the Stuarts. Parliament emerged as the leading force in government. The Hannoverians ruled as constitutional monarchs, limited by the laws of the land. During the 18th century, British monarchs ruled indirectly through appointed ministers who gathered and managed supporters in Parliament.. The Hannoverian monarchs associated the Whig Party with the revolution that brought them to power and suspected the Tory Party of Jacobitism. As a result, the Whigs dominated the governments of George I (1714-1727) and his son, George II (1727-1760). Neither king was a forceful monarch. George I spoke no English and was more interested in German politics that he was in British politics. George II was preoccupied with family problems, particularly by an ongoing personal feud with his son. Although they both were concerned with European military affairs (George II was the last British monarch to appear on a battlefield), they left British government in the hands of their ministers, the most important of whom was Sir Robert Walpole. George II Walpole led British government for almost 20 years. He spent most of his life in government, first as a member of Parliament, then in increasingly important offices, and finally as prime minister. Walpole had skillful political influence over a wide range of domestic and foreign policy matters.. Walpole kept Britain out of war during most of his administration. A growing sentiment in Parliament for British involvement in European conflicts forced Walpole to resign in 1742. In 1745 a Jacobite rebellion posed a serious threat to Whig rule. Led by Charles Edward Stuart, the grandson of James II, the rebellion broke out in Scotland. The rebels captured Edinburgh and successfully invaded the north of England. The rebellion crumbled after William Augustus, who was the duke of Cumberland and a son of George II, defeated the Jacobites at Culloden Moor in Scotland in 1746. British Colonial Expansion First British Empire Britain already controlled many overseas areas by the 18th century. For more than 100 years English explorers had ventured east and west in search of raw materials, luxury goods, and trading partners. The eastern coast of Canada gave the British access to rich fishing grounds, New England provided timber for the Royal Navy, the southern American colonies exported tobacco, and the West Indies produced sugar and molasses. From Asia came coffee, tea, spices, and richly colored cotton cloth. From western Africa came slaves who were sent to work on plantations in the Americas and the Caribbean. The first British Empire sprang from the enterprises of individuals and government-sponsored trading companies. They risked money, ships, and lives to establish England’s presence around the world. The British government created royal monopolies—private companies to whom the monarch granted exclusive rights to trade in a particular region or field of commerce. For example, the East India Company had a monopoly to trade in the east, the Royal African Company to enter the slave trade, and the Hudson’s Bay Company to exploit the fisheries of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. The lands that these companies claimed became possessions of the Crown, and investors bought shares in successful companies on the London Stock Exchange. Hudson’s Bay Company For over 200 years the Hudson’s Bay Company sent explorers and traders into the wilderness of Canada’s Northwest Territories. This 1882 illustration shows an expedition loading up on supplies at one of the company’s trading posts. The most important of Britain’s imperial possessions, however, were not trading posts but settled colonies in the Americas. In Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island, settlers established communities for religious reasons; in Virginia and Barbados, farmers, trades people, and merchants were in search of economic opportunity. As a result of successful wars with The Netherlands and Spain, England acquired New York and Jamaica, both thriving settlements. Prosperous cities sprang up along the eastern seaboard of North America in imitation of the towns of Britain. England’s colonies grew rapidly. The tens of thousands of settlers in the mainland North American colonies in 1650 grew to 1.2 million inhabitants by 1750. The Navigation Act of 1651 regulated trade between England and its colonial outposts. The act followed an economic philosophy known as mercantilism. Under this system, governments regulated economic activities by increasing exports and limiting foreign imports in an effort to generate wealth. According to the theory of mercantilism, the value of colonies lay in their natural resources, which could be transported to Britain and converted into exportable products. The Navigation Act benefited British merchants by restricting the types of products produced in the colonies, mandating that only British ships transport products to and from the colonies, and prohibiting direct trade between the colonies and other nations. Mercantile policies made Britain the greatest centre of trade in the world. Imperial Wars As a consequence of its military exploits under William III and the duke of Marlborough, Britain had become a great power. Britain’s military strength and its growing prosperity created an international rivalry among the three great colonial powers—Britain, Spain, and France. Spain controlled extensive colonies in Mexico and Central and South America. Because the Spanish and British empires both employed the restrictive mercantile system to regulate trade with their colonies, Spanish and British colonies were not allowed to trade directly with one another. The Spanish navy attacked British ships when they attempted to trade in South American ports. However, Spanish traders carried on a lucrative smuggling operation with the British colonies, exchanging sugar, rum, molasses, and other goods for raw materials and agricultural products from the British colonies. Relations were particularly tense between Britain and France. The French resented the expansion of Britain’s American colonies as well as the ban on direct trade between the colonies and nonBritish merchants. French territories in the Americas included Saint-Domingue (the largest of the Caribbean sugar islands), mainland North America from the Ohio Valley to the Mississippi River, and all but the easternmost part of Canada. Clashes between French and English forces became frequent in the North American colonies. . In the mid-1700s Britain became embroiled in two major wars. Both the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) were world wars, fought by great armies on the European continent, by navies in the Atlantic, and by privateers in the West Indies and the spice-rich islands of Asia. The War of the Austrian Succession erupted following the death of Charles VI, Holy Roman emperor and archduke of Austria. The war was fought over the succession of his daughter, Maria Theresa. It pitted England, The Netherlands, and Austria, who were trying to defend Maria Theresa’s succession, against an alliance of France, Spain, Bavaria, Prussia, Saxony (Sachsen), and Sardinia. After eight years of fighting, the conflict ended when the Treaty of Aix-laChapelle confirmed Maria Theresa as Charles’s heir. The treaty returned almost all the conquered lands to their original owners, except for the Austrian province of Silesia, which was ceded to Prussia. The Seven Years’ War was one of the greatest of all British triumphs. A coalition of Britain, Prussia, and Hannover fought against France, Spain, Russia, Austria, Sweden, and Saxony. The war began as a European conflict, when Maria Theresa attempted to regain Silesia from Prussia. It soon expanded into a major contest between Britain and France for control of their colonial empires. British prime minister William Pitt, 1st earl of Chatham, engineered the expansion of the war. Pitt was known as William Pitt the Elder to differentiate him from his son, William Pitt the Younger, who served as Britain’s prime minister in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Pitt’s family made its fortune in colonial trade, and Pitt saw clearly that Britain’s best interest lay in enlarging its colonial empire rather than in dominating Europe. In 1757 he captured Chandernagore, the principal French settlement in India, and at the Battle of Plassey he defeated the army of the Indian ruler of Bengal. These victories established a permanent British foothold in India. In North America, where the war was known as the French and Indian War, British general James Wolfe took Québec and drove the French from the province. At the conclusion of the war, Britain secured all French territory in Canada and east of the Mississippi and acquired Florida from Spain. The Treaty of Paris, which ended the war in 1763, represented a French surrender around the globe. Seven Years' War, Indian Theater Britain defeated the French at the Battle of Plassey, thus denying France control of Indian territories. The victory paved the way for more control by the English East India Company, which became the de facto government of the region. William Pitt, the earl of Chatham William Pitt, the earl of Chatham, led his country to victory over France in the Seven Years' War. He is also known for his defense of the rights of the American colonists. His son, William Pitt, became one of England's great prime ministers and led his country to prosperity after the financial ravages of the American Revolution. George III and the American Revolutionon Although William Pitt had become a national hero, he did not survive the change of monarchs in 1760. George III came to the throne determined to rule Britain without the help of the Whigs. He chose his former tutor, Lord Bute, as his first chief minister, but quickly replaced him with a series of successors. George III was determined to participate actively in Parliament’s political decisions; this brought him into conflict with his own ministers, who foresaw parliamentary opposition to a politically active monarch. The king also faced opposition from critics such as political reformer John Wilkes, a member of Parliament who was arrested for libel when he criticized one of the king’s speeches. George III Britain’s King George III governed during the time of the American Revolution. Besides losing the American colonies, the war nearly bankrupted his country. He took an active role in the British government and new territories were acquired to replace the loss of the American colonies. In his later years he suffered from bouts of insanity. Colonial Unrest Britain’s role in the imperial wars cost the country a staggering amount, and the national debt rose higher than it had ever been before. In order to lower the national debt, the king’s ministers decided to make colonial government pay for itself. Beginning in 1763 Parliament passed laws to tax colonial commodities such as sugar, glass, cider, and tea. The most controversial of these duties was the Stamp Act of 1765, which taxed legal documents and publications. Americans not only complained about the cost of these taxes, they also questioned the British government’s right to impose them. They decried being taxed by Parliament when they were not allowed representation in British government. The American Revolution (1775-1783) divided the governing classes in Britain. Prominent intellectuals such as political philosopher Edmund Burke were accused of treachery for supporting the colonists. However, the government of Prime Minister Lord North continued to try to enforce colonial taxation. In 1775, 13 of the American colonies rebelled against British rule. The American Revolution gave France and Spain an opportunity to strike back at the British Empire. Both supported the American colonists with money and ultimately declared war on Britain. The British army was unprepared for war in North America, and it suffered a series of humiliating defeats, culminating in the surrender of British general Charles Cornwallis to American forces at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781. When hostilities ended, Florida was returned to Spain, and the 13 rebellious colonies achieved independence as the United States of America. The loss of the American colonies came at great cost to Britain’s selfimage. George III was blamed for the disaster, and he decided to withdraw from direct control of government. He would soon have the first of a series of bouts with mental illness that eventually left him incapable of ruling the nation. Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquis Cornwallis British general, who achieved initial success against the American continental army in the American Revolution. But General George Washington, with the aid of a French fleet, surrounded Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia, and forced Cornwallis to surrender, ensuring an American victory in the war. Act of Union with Ireland In Ireland, Protestants formed volunteer military groups during the war, supposedly to defend the island from a French invasion. Backed by these groups, the Irish Protestants pressured the British government into granting greater independence to the Irish Parliament in 1782. This independence did not last long. In 1798 three antigovernment activities shook the confidence of the Irish Protestants. A revolt broke out in May and June among Catholic peasants, while a group of dissenting Protestants in Ulster also rose in rebellion; in August a small French army landed in western Ireland. All three challenges were handled by British troops. These events caused widespread concern among the Protestant elite about their ability to maintain political power in Ireland. In 1800 the Irish Parliament approved an Act of Union that made Ireland an integral part of the new United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The Irish Parliament was dissolved, and Irish representatives were seated in the British Parliament Revolution and War In 1783 the king turned power over to William Pitt the Younger, who was only 24 when he became prime minister. Pitt, the son of a former prime minister, immediately set about repairing the damage that had been done to the colonial empire by the recent losses. The India Act of 1784 removed the administration of India from the English East India Company and placed it directly under the control of the British government. Pitt’s greatest concern was to reduce the huge debt acquired from nearly a half century of warfare. He encouraged the resumption of trade with the United States. Pitt also created a fund to pay government creditors and to accumulate the money necessary to repay long-term loans. This strategy might have resulted in financial stability had it not been for developments in France. French Revolution In 1789 the French Revolution erupted. French citizens rose against their monarch, Louis XVI, eliminated the ancient legal distinctions based on social class, and established a republican government. The French revolutionaries invited all of the peoples of Europe to follow their example. Conservative monarchs throughout Europe were hostile toward the revolution. Within a few years wars broke out between France and a number of European powers. Battle of Trafalgar Britain’s warships defeated the combined fleets of France and Spain off Cape@ÿrafalァÿイ ÿゥÿ 1805Nÿÿhe victory gave Britain maritime supremacy that, except for clashes with French fleets during the Napoleonic Wars, remained unchallenged for more than a century. Horatio Nelson British naval commander Horatio Nelson gained fame and the gratitude of his country when he destroyed a combined French and Spanish fleet led by Napoleon that was prepared to invade England In 1793 France declared war on Britain, and the final phase of nearly 500 years of warfare between France and Britain began. It was a titanic struggle. Initially, Britain stayed out of the land war in Europe and chose instead to focus on defending its colonial possessions and maintaining control of the seas. In 1798 British admiral Horatio Nelson defeated the French navy in Egypt, securing India’s safety throughout the war. The Royal Navy captured nearly all of the important French colonies in the West Indies and Africa. In 1805 Nelson achieved one of the greatest of all naval victories at the Battle of Trafalgar when he defeated a combined French and Spanish fleet. Napoleonic Wars The Napoleonic Wars were fought between France and a variety of European nations from 1799 to 1815. Napoleon’s policy of blockading trade between Britain and the European continent hurt British trade. In response Britain instituted a blockade of goods going into or out of European ports controlled by Napoleon. The British policy of stopping and searching ships suspected of travelling to French-held areas of Europe led to the War of 1812 (1812-1815) between Britain and the United States. The war began when the United States insisted that Britain had no right to stop, search, or seize ships belonging to neutral countries. After Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812 and suffered a disastrous defeat, Britain mobilized its forces for a land war and joined a coalition with Russia, Austria, and Prussia. The center of fighting shifted to Spain, where a British force under the duke of Wellington successfully fought its way across the country and invaded France in 1813. Two years later Wellington led the coalition of forces that decisively defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo and ended the French revolutionary wars. The Congress of Vienna, which ended the Napoleonic Wars, was a great diplomatic victory for Britain. France was left intact but its continental neighbors achieved security of their borders. The treaty created a balance of power among the nations of Europe that led to 40 years of peace on the continent. With peace established in Europe, Britain was free to spend its energy and resources on expanding its overseas empire. Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington British general Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, is best known for his victory over Napoleon at the famous Battle of Waterloo in 1815. A leader of the Tory party in the British Parliament as well as a soldier, Wellington was known as the Iron Duke for his steadfastness. Industrialization and Progress