Ch. 6 Law - PhilosophicalAdvisor.com

advertisement

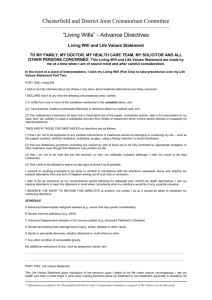

Legal Issues Death and Dying The Right to Die Leaving off the question of the morality or ethical permissibility of suicide, the law has been clear on 2 points regarding it: 1914: Justice Benjamin Cardozo, in the Schloendorff case asserts: “every human being of adult years and of sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body.” The book notes that this finding supported the right to refuse treatment … obviously, if it is wrong to treat a patient without consent, the patient must have a right to refuse treatment 1984: Bartling v. Superior Court contains the first explicit statement that a patient has the right to refuse life-sustaining treatment. The Bartling decision found that competence of the patient is crucial to determining the right to die Courts, however, have been reluctant to give a formal definition of competence Definition of Death 1980 the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) establishes 2 tests to determine death: 1. Irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, and 2. Irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem Anyone who passes either test is dead. Most states have adopted UDDA Determination of Death On p127, the book notes that UDDA was promulgated by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. That organization recommended these procedures for the declaration of death (these are not required by law): The ventilator should be removed after death is declared The physician (and not the family) should make the decision to declare death The physician may choose to consult with others (though the physician may choose not to) before declaring death The declaration should not be made by someone with an interest in the subsequent use of the tissue of the patient Persistent Vegetative State Persistent Vegetative State (PVS): Loss of all (or nearly all) higher brain function differs from brain death because the brain stem continues to function and the body is not dead Minimally Conscious State Due to the Terri Schiavo case, a distinction has been introduced between PVS and MCS, Minimally Conscious State. MCS: Severely altered consciousness Definite behavioral evidence of self-awareness, or evidence of environmental awareness Scientists have developed criteria to diagnose MCS: Functional interactive communication Functional object use There are currently no guidelines for the care of MCS patients; the book recommends patients be treated with dignity and recognize the potential for understanding the perception of pain. New Research into PVS Read this article on how brain scan technology has shown more PVS patients that previously thought are conscious. Owen's group performed fMRI on 54 minimally conscious and vegetative patients, and told them to imagine playing tennis if they wanted to answer "yes" and to imagine navigating the streets of a familiar city if they wanted to answer "no". Five of the patients were capable of answering the questions correctly in this way. All five had been diagnosed as being in a vegetative state, and only two of them responded to behavioural tests of awareness. –The Guardian Life-Sustaining Treatments The occasional difficulty of determining death, made worse by PVS and MCS issues, leads to questions about the use of life-sustaining treatments The difficulty of determining competence to make life-ending decisions also leads to these questions (read 131 on Competence) Life-Sustaining Treatments Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR): Only form of life-sustaining treatment performed without patient consent Perhaps only medical treatment initiated without the order of a physician Life-Sustaining Treatments Advance Directives (or Directives): Living Will Durable Powers of Attorney Formal documents that provide direction for health care providers should the patient become incapacitated Living Will In a living will a patient specifies what they would like done in specific cases, if they fall into an irreversible coma, lose the ability to breathe on their own, etc. State statutes governing living wills differ state by state Some can be executed by anyone at any time, even on behalf of minors Some require a waiting period if, say, presented by a terminally ill patient Some living wills expire while other’s duration is indefinite Durable Powers of Attorney An alternative to a living will is a Durable Powers of Attorney for Health Care Decisions (DPA) A competent person (the principle) empowers another (an agent) to make health care decisions in their stead, should they become incompetent The main advantage is breadth of scope: DPAs can be as detailed about care as one likes, more than a living will if desired, but allows the agent to make decisions not anticipated in a living will Family Consent Laws When no advance directive exists and the patient becomes incompetent, family consent laws come into play to formalize the family’s right to make health care decisions for the patient The book notes that this is a formalization of a standard practice or common practice Statutes differ from state to state, for example, Some require a certificate of incompetence before decisions are left to the family Some specify the order of decision authority must not be the same as that of inheritance beneficiaries No-Code Orders A ‘No’ code is a physician’s order not to resuscitate a dying patient In the mid 1980s, concern over liability led to hospitals adopting a ‘slow’ code, meaning, perform life-sustaining procedures but perform them half-heartedly That unwelcome situation led to clarification of Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders No-Code Orders Imaging professionals have to know the CPR status of each patient they treat to avoid liability for violating DNR orders (Do Not Resuscitate) Know where the information is kept on the patient’s medical record Check the status regularly This can vary from state to state you must check with your employer regarding no-code orders some states have partial code orders that specify which lifesustaining measures can be used