ACTIVE KILLING: WHAT THE LAW ALLOWS

Copyright © 2012. All rights reserved.

Over the past several decades there has been a proliferation of conflicts regarding whether or

not to provide life-sustaining care to certain individuals. These controversies have been fueled

by ideologically driven special interests groups and individuals who feel that some people are

better off dead, and have encompassed cultural and legal forces. This course seeks to prepare

the attorney for the legal issues that arise out of these disputes.

Example: Rachel Nyirahabiyambere survived the horror of the 1994

Rwanda Genocide, eventually immigrating to the United States on the

sponsorship of two of her adult sons. When she suffered a severe brain

hemorrhage in April, 2010, she was admitted to the Georgetown

University Hospital, where she remained in what the hospital called a

persistent vegetative state. Her sons hoped for a miracle, and claimed

that they saw signs of cognition at times . Because she had no health

insurance, and as a recent immigrant was ineligible for Medicaid, the

hospital balked at providing her care indefinitely. Meanwhile, her sons

puzzled about the alternatives available – they were unable to pay for

either continued medical care in a nursing hom e or through in-home

care. The decision of what care to continue was put off for seven

months. The hospital then issued an ultimatum: a guardian from outside

the family would be appointed to make a decision for the family.

Ms. Sloan, a nurse and a lawyer, was appointed guardian. She

determined that the feeding tube should be removed and Ms.

Nyirahabiyambere should be allowed to die by starvation and

dehydration against the expressed wishes of her family, who claimed

that she would never want to die this way, after having lived her life in

1

one amazing effort to survive after another. On February 19, Ms. Sloan

ordered the feeding tube removed.

Statements Ms. Sloan made in emails indicate that she erroneously

viewed her job as protecting the best interests of society, not her ward.

She stated, “Hospitals cannot afford to allow families the time to work

through their grieving process by allowing the relatives to remain

hospitalized until the family reaches the accept ance stage, if that ever

happens.” She also observed, “Generically speaking, what gives any one

family or person the right to control so many scarce health care

resources in a situation where the prognosis is poor, and to the

detriment of others who may actually benefit from them?” 1

After Ms. Nyirahabiyambere had been denied food for 21 days, attorneys

with the Alliance Defense Fund 2 obtained a temporary injunction

preventing the Sloan from control over Rachel’s food and fluids, and

requiring the re-insertion of the feeding tube. 3

As this situation illustrates, this type of life -and-death conflict requires

skilled attorneys to take the part of vulnerable, often medically and

cognitively disabled individuals, in order to procure the care they need.

The common conflicts -Patient is disabled, but the condition is not in and of itself life-threatening. A caregiver

or decision-maker for client attempts to have critical care removed. The patient’s wishes

are unclear. Alternatively, the patient’s wishes are undisputed, but the caregiver refuses

to continue care.

1

The manner in which the guardian was appointed also presented several reasons for caution: the family members

were removed from making decisions, their request to have an independent attorney appointed for their mother

was denied by Judge Nolan B. Dawkins of the Alexandria Circuit Court. See Deborah Sontag, The New York Times,

Virginia: Judge Orders Nutrition for Immigrant in Nursing Home, March 11, 2011,

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/12/us/12brfs-JUDGEORDERSN_BRF.html?_r=1&partner=rss&emc=rss; Peter

Jesserer Smith, Feeding tupe restored to immigrant woman unable to pay Jesuit hospital (Mar 11, 2011)

http://www.lifesitenews.com/news/breaking-feeding-tube-restored-to-immigrant-woman-unable-to-pay-jesuithosp; http://www.nationalreview.com/human-exceptionalism/322916/alliance-defense-fund-saves-livesmedically-vulnerable/.

2

Now known as Alliance Defending Freedom.

3

This case presents some unique issues, such as the impact of immigrant status, but in a broader sense, serves to

illustrate the fact that life and death dramas involving the medically vulnerable are arising with increasing

frequency.

2

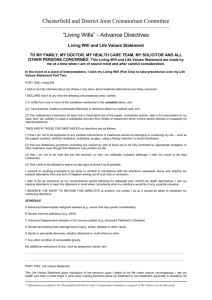

-Patient is suffering from a terminal illness, but is incapacitated to make health care

decisions, and their wishes with regard to provision of life-sustaining measures are

unclear or unknown, and decision makers are not in agreement as to appropriate care.

Both of the above scenarios, and various of the same,

are ripe for conflicts between family members,

between decision-makers and health care providers,

and combinations of these parties. To the emotional

nature of this type of conflict, add the incentives of

ideology and money, and it is easy to see how these

conflicts can rapidly escalate.

Note: This training does not advocate that life should

be prolonged artificially or indefinitely. Death is a

natural occurrence, and it is not the occurrence of

natural death that this training seeks to reduce, but

the devaluing of human life that occurs when certain

individuals are singled out unworthy of life.

It is important to make a crucial distinction between

cognitively disabled patients receiving tube-supplied

food and fluids, and actively dying people. The cases

[referred to in this course] concern the former,

people who are profoundly cognitively disabled and

whose tube-supplied food and fluids are removed

for subjective, nonmedical “quality of life”

considerations. There are other patients, however,

who as part of the dying process quit eating as their

organs shut down. This is a natural process. It would

be medically inappropriate—not to mention

pointless and cruel—to force nutrition and

hydration into these actively dying patients. (Wesley

J. Smith, Forced Exit, p. 276, at Creating a Caste of

Disposable People note 4 (hereafter referred to as

Forced Exit).)

Legalized Killing: A Slippery Slope

This seminar has its genesis in the case of Robert Wendland, who, at the age of forty-four, was

critically injured in a single-car accident in September 1993. Robert was in a coma for 16

months following the accident, but contrary to his doctor’s prognosis, he awoke in January

1995. Though still severely cognitively disabled, Robert progressed to to the point of being able

to recognize visitors, operate a wheelchair, and cooperate with a program of speech and

physical therapy.

In mid-1995, Robert’s wife, Rose Wendland, apparently underwent a change of heart about

Robert’s treatment. She decided that Robert’s feeding tube should be removed, which would

cause his death by starvation and dehydration. She allegedly had the approval of the hospital’s

ethics committee to order the removal of the feeding tube and was prepared to do so when an

anonymous caller notified Robert’s sister and mother of the plan.

3

The stage was thus set for In re Conservatorship of Robert Wendland,4 presenting for the first

time in California the issue of whether a person who is incompetent, but neither terminally ill

nor in a persistent vegetative state, can be legally starved to death.

Although Robert’s situation may sound unusual, those involved in defending his life soon

realized that the threat to him could be seen as part of a larger scheme to radically alter our

legal system to diminish, or even eliminate, protection for lives of the elderly, sick, and

disabled.

There has been a concerted effort within our society to categorize some persons as having lives

not worthy of being lived. This is a slippery slope: anyone diagnosed as in a persistent

vegetative state is “unworthy” of life. But the efforts do not stop there; they inexorably grow so

that anyone severely disabled may be viewed as “unworthy.” This begs the question, the end,

who will be considered worthy of life?

Indicators

that the culture is willing to view some as better off dead –

Assisted Suicide

Although physician assisted suicide is legal by statute in only two states5, there is an active

lobby for legalizing physician assisted suicide throughout the nation, and there are

organizations that actively facilitate and promote assisted suicide.6

Humane care: nonmedical care to

which every person is entitled in a

medical setting: warmth, shelter,

cleanliness.

From a historical perspective, state laws regarding the

withdrawal of food and hydration were initially grounded in

the common law of battery and the concept of informed

consent. From this common law sprang the right to refuse

Medical treatment: interventions

medical treatment. The right to refuse food and hydration

designed to benefit the patient,

was viewed as an exercise of this right. At the same time,

usually with the intent to cure the

most states expressly prohibit suicide and euthanasia. Laws

patient’s underlying condition.

in several of the American colonies confiscated the

–Forced Exit, 43-44.

property of individuals that committed suicide. While the

colonies eventually abolished such penalties, the courts continued to condemn suicide as “a

4

Wendland v. Wendland, 28 P.3d 151, (Cal. 2001), see below at pages 6-11 for more in-depth discussion of this

case.

5

See, The Oregon Death with Dignity Act, ORS 127.800 §1.01, et seq.; the Washington Death with Dignity Act, RCW

§ 70.245.010 et seq.

6

For example, pressure was being asserted on the Vermont legislature to legalize assisted suicide in April, 2011, as

reported at http://www.lifenews.com/2012/04/11/vermont-to-vote-on-measure-to-legalize-assisted-suicide/; in

November 2012, Massachusetts voters rejected an attempt to legalize assisted suicide, see

http://www.lifenews.com/2012/11/07/why-the-assisted-suicide-measure-lost-in-massachusetts/.

4

grave public wrong.”7 In most states, those assisting suicide are amenable to prosecution for

the homicide of those whom they assist to their deaths.

Euthanasia

It is but a step between assisted suicide and active

euthanasia (killing those unable or unwilling to make the

death decision for themselves). The idea of euthanasia has

become increasingly acceptable, and continues to be

promoted as a solution to various perceived problems such

as the financial burden of continued care for those suffering

severe disability.

The “food and fluid” cases have

rippled through traditional medical

ethics and public morality,

undermining one of the primary

purposes for which our government

has been instituted: the protection

of the lives of all its citizens.

–Forced Exit, 44.

De Facto Euthanasia - Removing foods and fluids

In order to understand the radical

changes that transformed medical

ethics during the last twenty years, we

must discuss two related but distinct

concepts: The first is the absolute right

of all patients, no matter what their

condition, to receive humane care. The

other is the right of patients or their

surrogate decision makers to refuse or

discontinue unwanted medical

treatment.

Although today active euthanasia is not permitted by law in

the United States, it has become accepted practice to

remove life-sustaining nutrition and hydration from certain

patients. Once considered routine humane care, food and

fluids are now defined as medical treatment – at least

when supplied through a feeding tube. This redefinition

has created a vehicle to intentionally end the lives of

cognitively disabled people while retaining the pretense of

ethical medical practice.

It was not too many years ago that

food and fluids were considered

humane care. That is no longer true, at

least for food and water supplied

through a feeding tube. Such care has

been redefined as medical treatment,

creating a vehicle to intentionally end

the lives of cognitively disabled people

while retaining the pretense of ethical

medical practice. -Forced Exit, 4344.

This fundamental change in the definition of medical care

came about as the result of a deliberate campaign, which

progressed from an academic theory (that healthcare costs

and patient autonomy could be forwarded by removal of

nutrition and hydration) to active pursuance of test cases

(whereby the bounds of the law were stretched and

shaped). The courts were convinced that the ethics had

been carefully worked out, and the power of removal of

sustenance would be exercised only within the clearest

guidelines.8 Thus, we have a society, which less than fifty

years ago would not consider starving a cognitively

7

Americans United for Life, Defending Life 2010,page 416, Preserving Human Dignity at the End of Life: A survey of

federal and state laws, Jessica J. Sage. Note, competent patients are uniformly capable of refusing medical

intervention.

8

Forced Exit, 44.

5

disabled person to death, which today thinks it the morally appropriate in specific

circumstances.

And this is how the slippery slope works: Once the killing of the permanently unconscious is

permitted, those actually killed include others, such as those who are conscious but cognitively

disabled. If the ethical guidelines are not being followed, instead of enforcing those guidelines,

the guidelines are simply expanded to swallow up an ever expanding group of persons

considered unworthy of life.9

The impetus for limiting care has never been stronger. Spiraling health care costs have led to

measures aimed at curbing costs and providing more people with insurance coverage, such as

the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Obamacare).10 As cost-saving elements of this

law are implemented, it is reasonable to expect additional pressure to be brought to bear in

favor of terminating treatment for certain individuals.

The discussion that follows seeks to both inform the attorney and to provide the

resources needed to effectively defend those weak and vulnerable people confronted

with this type of crisis.

Strategies and Tactics –

Termination of treatment controversies usually involve relatives of an adult patient who dispute a

decision to end life-sustaining treatment for the patient (keep in mind that life-sustaining treatment

includes nutrition and hydration).

Know the Facts –

Before taking a case, be sure to understand the facts and the parties. Who is the client? Are you

representing the patient alone, or the patient and various members of the family, or relatives of the

patient? What are his or her values and lifestyle? Who is the opposition? Is it a family member of the

patient? Is it the caregiver? What has transpired to date? What do you wish to prevent the opposing

party from doing, or to compel the opposing party to do?

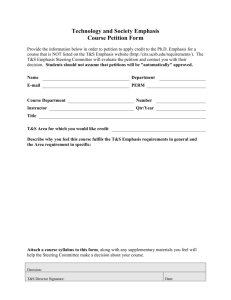

Know the Law –

What legal claim can the client assert? What is the legal basis of the claim? Helpful tools in determining

the legal claims involved are included in the Appendices, see particularly Appendix C—F and K.

One common controversy might involve relatives or interested third parties who wish to stop

life-sustaining treatment of an individual in order to hasten death, while other family members

9

Id. at 45-50.

See Appendix H.

10

6

or interested third parties object to those wishes. A legal dispute over conservatorship ensues as

the disputing parties seek to substitute their judgment for that of the patient.

An example of this controversy is the landmark California case, Wendland v. Wendland, 28 P.3d 151,

(Cal. 2001).

Wendland Case –

As stated above, Robert Wendland was involved in a single-car automobile accident in September 1993.

The accident left Robert comatose for approximately sixteen months. Despite the doctor’s prediction

that Robert would not regain consciousness, he awoke in January 1995.

Eventually Robert regained voluntary reactions and responded to certain commands, such as directives

that that he could follow by operating his motorized wheelchair. A court investigator who spent time

with Robert wrote in documentation to the court that he was likely to improve to the point of being able

to speak and feed himself. Robert recognized his mother and sister. He acted volitionally, and showed

definite mood swings, depending on who he was with or if the hospital staff attempted to treat him

using methods that made him uncomfortable. He worked himself to exhaustion in physical therapy on

some days; other days he was not so cooperative, indicating frustration with his physical condition.

Robert’s sister witnessed Robert thumb through a magazine. His condition showed continued

improvement.

In July of 1995, Robert’s wife, Rose in consultation with Robert’s doctor, agreed that he should undergo

an extensive program of speech and physical therapy. After Robert began the program, Rose had an

abrupt change of heart and determined his feeding tube should be removed. Robert had no written

directive for health care. He received all of his nutrition and hydration through a feeding tube. If the

feeding tube was removed, he would die by starvation and dehydration—not from any complication

related to his physical condition.

Rose (with Robert’s doctor) sought the endorsement of Lodi Memorial-West Hospital’s ethics committee

to remove his feeding tube. Under their plan, which allegedly obtained the committee’s approval,

Robert would be discharged and moved to a convalescent home where his feeding tube would be

removed. There Robert would die by dehydration and starvation, which takes from eight to thirty days

according to medical experts.11

Fortunately, an anonymous caller notified Robert’s sister, Rebekah Vinson, and his mother Florence

Wendland, of the intended plan to move Robert and stop his care. Rebekah and Florence sought legal

assistance. Their attorneys persuaded the court to grant injunctive relief, prohibiting the cessation of

Robert’s life-sustaining treatment and prohibiting his transfer from Lodi Memorial Hospital-West. Rose

petitioned the court to be appointed as Robert’s conservator, and again sought to kill him.

Rose was appointed conservator over the objections of Rebekah and Florence, who contested Rose’

petition and filed a cross-petition to be appointed co-conservators. Although Rose was appointed

11

7

See Appendix B for a description of the process of death by starvation and dehydration.

conservator, the court limited her authority to act on Robert’s behalf. Rose was given no authority to

direct the termination of treatment or the removal of the feeding tube.

The parties returned to court for trial in October 1997 to litigate the matter of termination of Robert’s

treatment, thereby determining Robert’s fate. The trial court and all parties agreed to a bifurcated

proceeding at trial. The first proceeding, which was concluded in November 1996, determined the

foundational issues to be decided at the second proceeding. The second proceeding was to determine

whether or not it was in Robert’s best interests to have his feeding tube removed.

Pretrial proceedings

The pretrial proceedings included the following exchange of pleadings between the parties:

Opposition to Petition of Rose Wendland to be Appointed Conservator and Cross-Petition for

Appointment of Rebekah Vinson and Florence Wendland as Co-Conservators: Hearing held

September 1995, in response to Rose’s petition to be appointed conservator. Prior to her

appointment as conservator, a court investigator interviewed all parties, including Robert. The

court investigator recommended that independent counsel be appointed to Robert.

Petition for Appointment of Independent Counsel: Filed in January 1996 after several informal

attempts to have counsel appointed to Robert. Rose opposed the petition. A hearing was held

by the trial court in February, 1996 and petition for appointment of counsel was denied.

Petition for Writ of Mandate Regarding Appointment of Legal Counsel: Filed February 1996, in

the Court of Appeal, Third Appellate District of California. Petition denied.

Petition for Review Regarding Appointment of Legal Counsel: Filed in February, 1996, in the

California Supreme Court. At the direction of the Supreme Court, the appellate court vacated its

original action and issued an alternative writ of mandate. No response was made by Rose. Upon

review by the appellate court, it was concluded Robert was entitled to appointment of

independent counsel. The decision was then certified for publication. Wendland v. Superior

Court, 49 Cal.App. 4th 44 (1996).

Memorandum of Points and Authorities Addressing Medical/Ethical Issues: Filed October,

1996. In September, 1996, Rose directed the hospital to change Robert’s status from “full-code”

to “no-code” status, meaning no heroic measures would be taken to save his life if a medical

emergency presented itself. Petitioners argued that if no measures could be taken to save

Robert’s life an emergency, this would be tantamount to Rose terminating medical treatment.

The trial court heard the matter in October 1996, and in November 1996 issued an opinion that

the no-code directive was distinguishable from removing life-sustaining treatment.

Memorandum of Points and Authorities on Legal Issues Before the Court in Phase I of

Bifurcated Proceeding: Filed November 1996. First part of bifurcated trial held week of

November 12, 1996. The issues decided at this proceeding are discussed in detail below.

8

Petition for Writ of Mandate Regarding No-Code Status: Filed December 1996, in the Court of

Appeal, Third Appellate District of California. Petition denied.

Petition for Review Regarding No-Code Status: Filed in December, 1996, in the California

Supreme Court. Petition denied.

Trial proceedings

As explained above, the trial was a bifurcated proceeding.

The first trial proceeding, completed in November of 1996, was necessary because Wendland was a case

of first impression in California. At issue was whether or not an individual, who is neither terminally ill,

nor in a persistent vegetative state or coma, will have life-sustaining treatment withdrawn at the

direction of the conservator, resulting in death not related to the conservatee’s medical condition.

The court made the following determinations as to the legal standards in this case:

1. The standard of proof with regard to Robert’s wishes to withdraw life-sustaining treatment

would be one of clear and convincing evidence;

2. The conservator who wishes to withdraw life-sustaining treatment, has the burden of proof at

trial; and

3. The court should apply the best interests of the conservatee standard.

In determining the standard of care applicable to decisions by the decision maker, the court considered

the various standards that had been applied to other contexts of surrogate decision making.

9

-

Subjective Standard: Although the word “subjective” typically would indicate otherwise, this

is the most stringent of the three standards. The decision to terminate life-sustaining

treatment is made by asking what the patient would have wanted when he was competent.

If there is no evidence of the patient’s preference, and if the statement of intent is not

explicit, or even if the patient was never competent, treatment cannot be withheld.

-

Substituted Judgment Standard: Using this standard, a court asks what the patient would

have wanted if competent. This differs from the subjective standard in that, using

substituted judgment, the court infers what the patient would want considering many

factors, such as the patient’s personality, lifestyle, values, philosophical stance, religious

attitudes, moral views, and attitudes about medical issues. Based on such factors, and even

with no explicit statement of intent from the patient while competent, the surrogate may

terminate medical treatment.

-

Best Interest Standard: This is an objective standard by which the decision to withdraw lifesustaining treatment would be made, looking at what is best for the patient medically,

without regard to evidence of the patient’s wishes. The best interest standard is the most

commonly used standard in the medical community and some courts have adopted its use

in making end-of-life decisions.

Robert’s Wishes: What Robert would have chosen had he been capable of making his own decision was

in dispute. Rose argued that he had made a verbal “statement of intent.” However, this statement was

made in a heated discussion while Robert was suffering from a hangover. This was also at a time when

Robert was abusing alcohol and grieving the death of a close family member.12 Both Rose and Robert’s

brother testified as to the statement’s veracity. The appellate court’s reasoning, discussed in the context

of appointing Robert independent counsel, is noteworthy: “a person facing the final accounting of death

should not be required to rely on the uncertain beneficence of relatives.”

Medical Experts: Dr. Ronald Cranford,13 a neurologist, testified as an expert as to recommended

guidelines for termination of the treatment of the “minimally conscious.” Under these guidelines, the

parameters used to gauge whether a “minimally conscious” person should be deprived of life-giving care

consist of the following factors:

1. Patient well being, assumed to be inconsistent with being disabled;

2. Patient autonomy, assumed to trump the right to life;

3. Integrity of the medical profession, as discussed by the United States Supreme Court in the Vacco and

Washington decisions.

4. Social Justice, or a proper allocation of resources.

Cranford, sought to minimize Robert Wendland’s value as a person during his testimony, opining that

“an unconscious person should have no constitutional rights.” Cranford asserted Robert’s inability to

conceptualize the significance of particular tasks he performed (such as combing his hair) rendered him

nothing more than a “trained animal,” and he criticized the medical personnel's efforts to help Robert

improve and sustain his current condition as inhumane prolongation of an existence he dubbed a “living

death.” He concluded Robert did not have a right to life due to his cognitive disability and “minimally

conscious” state.

Retained medical experts opposed to ending Robert Wendland’s life-sustaining treatment testified that

the guidelines Dr. Cranford advocated are valid neurological assessments only insofar as they categorize

patients for purposes of treatment, such as hospital placement and treatment plans. These experts insist

such categories are not, and should not be guidelines in making life and death decisions for “minimally

conscious,” or incapacitated patients. (It is imperative that expert witnesses making arguments similar

to those of Dr. Cranford be impeached by sound expert medical.)

12

(It is in this type of situation where expert testimony about the effects of alcohol abuse may be needed because

those experts advocating Robert’s death testified his alcohol consumption did not affect his state of mind when

making that statement. They also dismissed the fact that he may have been suffering from depression.)

13

Dr. Cranford has testified at other cases of this nature, including Terri Schiavo’s case.

10

Motion for Judgment: After the conservator, Rose, presented her case in the second trial proceeding,

Rebekah and Florence made a motion for judgment, asking that the case be dismissed because the

conservator failed to show by clear and convincing evidence that it was in Robert’s best interest to be

actively killed, eliminating the need for Rose and Rebekah to present their case.

Trial Court Decision: The trial court applied the clear and convincing evidence and found the evidence

insufficient to prove that the conservator's decision was in accordance with either the conservatee's

own wishes or best interest.

Appellate proceedings

The appellate court believed the trial court was required to defer to the conservator's good faith

decision.

However, the state supreme court, construing Cal. Prob. Code § 2355, held that the trial court correctly

required the conservator to prove, by clear and convincing evidence, either that the conservatee

wished to refuse life-sustaining treatment or that to withhold such treatment would have been in the

conservatee's best interest. Lacking such evidence, the trial court correctly denied the conservator's

request for permission to withdraw artificial hydration and nutrition. Conservatorship of Wendland, 26

Cal. 4th 519 (Cal. 2001).

Handling the Case –

Hypothetical: you are contacted by Jane Roe whose brother Joe Roe, age 75, is unconscious from an

auto accident; Joe’s wife, wants to remove Joe’s feeding tube and discontinue all medical treatment for

Joe’s condition; there is no advance directive or appointed decision-maker; but Jane feels that Joe would

want to live based on his lifestyle and value system. She feels that Joe’s wife has an ulterior motive in

wanting him dead: she wants to collect his life insurance money and marry her longtime lover Hank.

What should you do?

-Interviews and Declarations

Talking with the client, the family of the client, the hospital and caregivers involved will provide

background information, and will lead to the appropriate persons to make declarations in support of

your position. For example, find out

-what are Joe’s underlying medical conditions? What is his prognosis?

-what evidence is there of Joe’s wishes? His values? His religion?

-what do other family members think?

-what evidence is there of wife’s bad motive?

11

-how is the hospital responding? Have they agreed to follow wife’s instructions? Are they urging

her to discontinue treatment?

-is there a medical expert available who can confirm/counterbalance Joe’s doctor’s conclusions?

Get to know your client—see whether the facts line up, whether client has “clean hands,” especially if

there is a dispute between family members. Family disputes are messy, and it’s good to be appraised of

family disagreements at the forefront.

Prepare client with reasonable expectations—remember the type of remedy you are seeking

(injunction? Appointment of conservator? Temporary restraining order?)

In a good scenario, it may be possible to resolve the dispute without going to court:

-contact hospital directly via a demand letter14 or meeting with “ethics committee” or hospitalist

(below).

Hospital Ethics Committee

In the typical hospital setting, the decision to end life-sustaining treatment goes through a

recommendation process from the ethics committee of the treating hospital. When a request for

withdrawal of life-sustaining care is presented, the committee will seek to ensure the “appropriate”

decision-maker is making such a request. If the person making the request is deemed appropriate,

removal of life-sustaining treatment is usually sanctioned.

Whatever decision the ethics committee arrives at, the findings made at the ethics committee and facts

upon which their decision is based may be helpful (or harmful) to the client who objects to their

recommended course of action.

If possible, the client who disagrees with the decision to remove life-sustaining care should seek to

participate in the ethics committee process. Just having opposing counsel present to give another

opinion on the decision can sometimes result in a positive outcome for the patient.15

Evidentiary Issues

It is important to anticipate the evidentiary hurdles involved with use of facts at a hearing on a petition

for removal of life-sustaining treatment.

For example, in Robert Wendland’s case, witnesses testified at pre-trial hearings that the ethics

committee sanctioned the request of the conservator to remove Robert’s feeding tube. No objections

were made to testimony of the ethics committee proceedings.

14

15

See Appendix G for a sample demand letter.

See Appendix G for a sample demand letter.

12

Subsequently, during depositions, the objectors to removal of Robert’s life-sustaining treatment

(Florence and Rebekah) attempted to question the a witness about those same ethics committee

proceedings. The witnesses who had previously testified as to the content of the ethics committee

hearing objected to questions, claiming that the hearings were privileged, and during trial, legal counsel

for the hospital brought a motion to quash the subpoena requesting hospital documents from the ethics

committee proceedings, also on the basis of privilege.

Since the ethics committee recommendation would carry weight with respect to the court’s decision in

Wendland, objectors wanted the court to be fully aware of the issues considered in the committee

proceedings. Objectors had not been a part of the ethics committee hearing. Further, the veracity of the

witnesses’ testimony could not be substantiated without committee proceedings as part of the record at

trial.

The court eventually ruled that the ethics committee proceedings were privileged, but the privilege had

been waived due to the witnesses’ previous testimony at the pretrial hearing. Thus, questions regarding

the previous testimony were appropriate within the scope of the previous testimony.

A pretrial motion to exclude evidence may be appropriate. In the above case, exclusion of all reference

to the privileged ethics committee hearing would have clarified the issues, and saved time at the

hearing.

Petition In Superior Court

If efforts to convince caregivers to continue treatment are ineffective, a petition for order authorizing

medical treatment may be filed in the Superior Court (in California) pursuant to California Probate Code

§§ 3200 et seq., §§ 4600 et seq.16 In the petition it is essential to set out the facts, and it may be

necessary to include a petition for an emergency ex parte order to prescribe the health care of the

patient in the short term. File a separate memorandum of points and authorities to more fully explain

the legal basis of the claim, including relevant case law. 17

Include declarations in support of the petition as appropriate, such as those of the relatives who wish to

continue treatment, and physicians who agree that treatment is appropriate. 18

Finally, provide a proposed order for the court. 19

Direct The Thinking of The Trier of Fact

Because of prevalent thinking within society (that some life is not worthy of being lived) it is essential to

direct the trier of fact’s thinking with regard to the termination of treatment that will result in death.

Proving the Patient’s Present Condition

16

See Appendix C through G for examples of the petition and supporting documents.

See Appendix C.

18

See Appendix F.

19

See Appendix E.

17

13

It is not out of the ordinary for proponents of termination of treatment to misrepresent the physical and

mental condition of the patient. For example, in Terri Schiavo’s case, there was dispute over the issue of

whether Terri was in a persistent vegetative state (a condition that is misdiagnosed an estimated 43% of

the time).20 Part of the difficulty in that case was the inability to overcome the initial diagnosis of PVS

that the trial court continuously reverted to in ruling for removal of life-sustaining care.

One thing especially helpful in overcoming mischaracterizations of condition are videotapes of the

patient’s actual capacity. It is imperative to videotape the patient prior to any court action or court

order disallowing visitation, and/or photos or videotapes. Even if the court does not prohibit

videotaping, a conservator who is advocating termination of treatment can control access to the

conservatee, as in the Wendland and Schiavo cases. In Robert Wendland’s case, it was not until

videotape was released to the press that anyone questioned whether his life-sustaining treatment

should be terminated. Most were under the impression he was comatose, when in fact he was

conscious and interactive with his environment. Videotapes were important because they conveyed his

humanity.

Without videotapes, the individual is just a name whose condition will be shrouded in secrecy in the

name of the right to privacy. It is very easy to dehumanize those you cannot see. Show the world and

the court the incapacitated individual’s humanity using video recordings.

Opening Statements

The case for life must begin at opening statements. The parties and the court are likely to lack education

on essential topics. Arguments that may be persuasive include the following:

-There is no constitutional right to die;21

-Our very legal structure is premised on the notion we have value and rights as individual humans;

-Traditionally and socially physicians and those in the medical profession have the role of healers, not

harmers;22

-The decision to end treatment is not medically sound and is not in the patient’s best interest;

-Although a patient can refuse continued treatment for himself or herself via written directive,

determining the patient’s wishes absent a written statement (assuming such does not exist)is a serious

and undertaking considering the permanent nature of the consequences (death).

Examining Medical Experts

20

David Gibbs, Fighting for Dear Life, Bethany House 2006, pages 26 and 64. Note, a full discussion of the Schiavo

case is beyond the scope of this course, for further study on the topic see Diana Lynne Terri’s Story, WND Books

2005.

21

This has been firmly established by the U.S. Supreme Court in Wash. v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997), Vacco v.

Quill, 521 U.S. 793 (1997).

22

See e.g., Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702, 703-704, 731 (1997).

14

When questioning medical experts who advocate death scrutinize their professional evaluation. Did they

question all the parties involved? With what degree of certainty did they make their evaluation and

prognosis of the patient’s condition? Question them about options and direct them in your questioning

so that they must explain why continued treatment is not preferable to ending treatment. Ask why

appropriate palliative care wasn’t recommended instead of removal of nutrition and hydration.

Ask the medical expert to describe the dying process.23 It is one thing to discuss “removing medical

treatment.” It is quite another when you understand the result of removing such treatment.

Retained Experts

The Wendland trial is an example of why caution with experts is necessary. During testimony at trial,

one of the conservators’ expert witnesses revealed that the objector’s retained expert (a bioethicist who

was to have advocated for continuation of Robert’s life-sustaining treatment), communicated with the

conservator’s witness (who advocated the removal of treatment). After their communication, objector’s

expert withdrew from the case.

Objectors were subsequently unable to find another bioethicist. When subsequent bioethicists were

contacted, the uniform response was one of empathy for the conservator’s position, or that their area of

practice was not related to termination of treatment cases.

Keep in mind experts retained by both the conservator and Robert’s court appointed attorney

advocated for his death. Their testimony revealed that several of the expert witnesses retained by the

conservator and by Robert’s counsel were acquainted. Although there was no evidence to show

improper communication between the experts who testified at trial, all testimony was virtually the

same.

There appears to be a growing consensus of the “quality-of-life ethic” among such experts, and

advocating death follows that ethic. Therefore, the following precautions are recommended with

experts in termination of treatment cases:

1. Make it clear to potential expert witnesses that all preliminary communications are

confidential.

2. Carefully check the curriculum vitae of any potential expert. Question the mission and

purpose of any other professional affiliations, groups, or memberships named.

3. Review articles and other publications authored by experts. Compare the sources cited in

their publications and articles.

If the witness advocates death, minimize the effectiveness of such testimony as early as possible (such

as during viore dire) by bringing to the attention of the trier of fact the following about the field of

bioethics:

1. The label “bioethicist” is fairly new

23

For an example of such a description, see Appendix B.

15

2. There is no state or federal licensing agency, or any private regulatory agency to maintain

quality control on the profession

3. There are no governing rules of conduct for bioethicists and no remedy for improper

conduct from the profession.

Based on the foregoing, ask the court to disqualify, or at the very least limit the scope of the testimony

of the bioethicist. It is likely that the court will allow the bioethicist to testify as an expert. If so, during

cross-examination ask for specifics on the following:

1.The number of termination of treatment cases consulted on and whether or not the expert

advocated termination in those cases.

2. The number of active killing cases consulted on and whether or not the expert advocated

active killing.

3. Specificity as to the number of those cases that are similar in their facts to the case at hand.

4. The basis of the opinion to terminate treatment rather than to provide palliative care, such as

publications that establish the authority upon which the bioethicist bases an opinion.

5. Professional memberships, and what the member organizations advocate with respect to

termination of treatment and active killing.

Motion for Judgment

A potential way to shorten the trial process is a motion for judgment Under California Code of Civil

Procedure §631.8, which can be brought after one party has concluded their presentation of evidence. If

the court hears the motion, the evidence must be weighed as presented by the party against whom

judgment is sought. If the court grants the motion, the “judgment operates as adjudication upon the

merits.”

The objectors successfully brought a motion for judgment at the Wendland trial at the close of the

conservator’s case. The conservator, who sought to terminate Robert’s life-sustaining treatment, had

the burden to prove by clear and convincing evidence that it would be in Robert’s best interests to have

such treatment removed. The court agreed with objectors that the burden of proof had not been met

when the conservator rested her case.

Closing Statements

Another opportunity to persuade and educate occurs at closing arguments. Give the trier of fact a way

out of making the permanent decision to end treatment.

Points to be made at closing arguments:

If the death of a cognitively disabled man is advocated because his condition will never improve,

ask the trier of fact why this man’s life is dependent upon improvement. Then tie this to the

16

public policy established by the history and tradition in the United States of protecting its most

weak and vulnerable members of society. This tradition should dictate to the trier of fact

protection for the disabled, elderly, and chronically ill. If there is a doubt, the safest course is to

preserve life—this at least is not an irrevocable decision.

If the case involves novel issues, reestablish that the courtroom is an inappropriate place to set

public policy with regard to ending life-sustaining treatment.

Directing the termination of a cognitively disabled person’s life-sustaining treatment is, and

should remain, unprecedented. No court has allowed the withdrawal of life-sustaining

treatment from a person who is not PVS,24 terminally ill, or in a coma without their permission

and consent.

Medical evidence does not show that it would be in the individual’s best interest to end his

life—If the patient is not comatose, PVS, or even if he is terminally ill, there are other choices

available besides death through dehydration and starvation.

a. Treatment for depression, pain, and other symptom is available. There have been

tremendous advances in the science of pain management.

b. Disability, old age, and even terminal illness are not medical conditions that need to be

“treated” by death.

c. Any unanswered questions about the patient’s medical condition should prompt us to

err on the side of the preservation of life.

d. Highlight any improvement at all in the patient’s condition. However, continued

improvement should not be the sole test by which the decision to end life should be

made—the life itself is of inherent value.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees the right to life, liberty, and

pursuit of happiness. Legislation such as the American’s with Disabilities Act reaffirms those

rights, prohibiting discrimination on the basis of disability. This affirms that as a matter of policy,

we should value and protect those who are disabled, not see incapacity as a license to eliminate

them.

Bias against the “family of origin”— Any expert opinion is suspect if the expert did not consider

all family members’ opinions on the issue of termination of treatment. At the Wendland trial,

experts distinguished between the “family of origin” and the “immediate family,” implying that

because the immediate family was by nature closer to Robert, their opinion to withdraw lifesustaining treatment held more weight. (The family of origin is defined as parents and siblings;

the immediate family as spouse and children.) Even close family friends’ opinions on appropriate

care for Robert carried more weight with pro-death experts than Robert’s mother and sister.

24

At least diagnosed as PVS—this diagnosis is often of questionable use. See note 13, supra.

17

Due to the bias against the family of origin, experts did not take the time to meet with Robert’s

mother and sister as they did with the immediate family. Therefore, the expert analysis was

skewed based on a biased view of Robert’s personally held beliefs. His view was central to the

case because of the combination approach the court sanctioned, combining the best interests

standard with the substituted judgment standard when making the determination whether or

not to withdraw life-sustaining care. A similar analysis can be made with any termination of

treatment case, whether the individual is disabled, elderly, or terminally ill.

The unreliability of general statements made pre-incompetency about not wanting lifesustaining care—Whether incompetent due to disability, age, or illness, any pre-incompetency

statements of the patient should be viewed cautiously.

Stress that undocumented or uncorroborated statements are suspect. Scrutinize any general

statements, even if corroborated. For example, all of us have made general statements at one

time or another like, “I wouldn’t want to live like that.” As in the case of Robert Wendland, it is

one thing to make such an offhand statement, and quite another to die by starvation and

dehydration based on such an utterance.

The uncertain beneficence of relatives—The care of an incapacitated family member is not

something wished for, but it is a part of life. Family members who find the care of an

incapacitated loved one tedious or unbearable may have underlying motives in wanting to

terminate life-sustaining treatment, ranging from the need to move on with relationships, an

inheritance, or emotional difficulty with a painful situation.Alternatives and/or assistance with

such situations is readily available. Death for the incapacitated individual is not the only answer.

The right to life is not qualified by any specific criteria.

California Probate Code §2355 requires medical decisions to be based on the wishes and values

of the patient. Use the facts to establish the wishes and values of the patient, and urge a

decision consistent therewith.

Persuasion, Precedent and Appeals

Remember there is a dearth of education on active killing. What is presented during trial may be the

only education the court has on the issue of terminating treatment for disabled persons. Thus, the

persuasive impact of your arguments has the

In defending the innocent, disabled and

potential to impact not only the case at hand, but

those down the road.

defenseless against the threat of death, the

Present the case, including motions, with the

appeals court in mind if there is precedent-setting

potential in your case. For example, the Wendland

case went through numerous appeals, ending at

the California Supreme Court.

18

attorney fulfills the highest calling of the law

as a profession, and helps to preserve the

decency and justice of a society too often bent

on self-fulfillment at the cost of all that

should be held sacred.