EVANS ENGL 320 PP Sept 14

advertisement

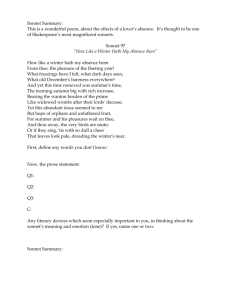

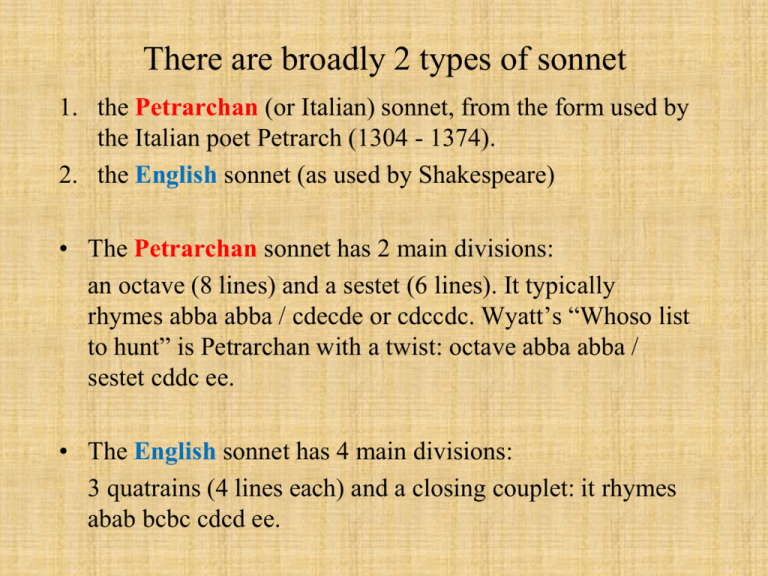

There are broadly 2 types of sonnet 1. the Petrarchan (or Italian) sonnet, from the form used by the Italian poet Petrarch (1304 - 1374). 2. the English sonnet (as used by Shakespeare) • The Petrarchan sonnet has 2 main divisions: an octave (8 lines) and a sestet (6 lines). It typically rhymes abba abba / cdecde or cdccdc. Wyatt’s “Whoso list to hunt” is Petrarchan with a twist: octave abba abba / sestet cddc ee. • The English sonnet has 4 main divisions: 3 quatrains (4 lines each) and a closing couplet: it rhymes abab bcbc cdcd ee. William Shakespeare, The Chandos Portrait. National Portrait Gallery, London. 1609 title page of first edition of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. SHAKE-SPEARES SONNETS. Neuer before Imprinted. At LONDON By G. Eld for T.T and are to be solde by John Wright, dwelling at ChristChurch gate. 1609. Sonnet 20, 1609 printed edition. Shakespeare, Sonnet 20 A woman’s face with Nature’s own hand painted Hast thou, the master mistress of my passion; A woman’s gentle heart but not acquainted With shifting change, as is false women’s fashion; An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling, 5 Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth; A man in hue all hues in his controlling, Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth. And for a woman wert thou first created, Till Nature, as she wrought thee, fell a-doting, 10 And by addition me of thee defeated, By adding one thing to my purpose nothing. But since she prick’d thee out for women’s pleasure, Mine be thy love, and thy love’s use their treasure. Questions • How do we understand the speaker’s desire in Sonnet 20? • How does this understanding matter to us today?? thing/nothing (l. 12) • thing (1) object; (2) generative organ (used both for “penis” … and for “vulva”) • nothing (1) worthless; (2) no-thing, a non-thing. “Nothing” and “naught” were popular cant terms for “vulva” (perhaps because of the shape of a zero). Booth 1977, 164 Sonnet 20: Even the speaker’s apparent disclaimer of any active, genital sexual interest in the youth … suggests a light-hearted equivocation [the pun on “nothing” as both male and female genitals]. (I do not make this point in order to assert that the Sonnets say that there was a genital sexual relationship between these men; … the sexual context of that period is far too irrecoverable for us to be able to disentangle boasts, confessions, undertones, overtones, jokes, the unthinkable, the taken-for-granted, the unmentionable-but-often-done-anyway, etc.). (Sedgwick 1985, 34–5) Nicholas Hilliard, Portrait of a young man among roses. 1585-95 What can be said is that the speaker in this sonnet [20] can, for one reason or another, afford to be relaxed and urbane … on the subject of sexual interchangeability of males and females – as long as he is addressing a male. And this closeness between males, to which a reader from outside the culture finds it difficult to perceive the boundaries, seems to occur within a suasive [serving to persuade] context of heterosexual socialization. (Sedgwick 1985, 34–5) References • Booth, Stephen, ed. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1977. Print. • Goldberg, Jonathan. “Part One: ‘Wee / Men’: Gender and Sexuality in the Formations of Elizabethan High Literariness.” Sodometries: Renaissance Texts, Modern Sexualities, Stanford: Stanford UP, 1992. 29-101. Print. • Sedgwick, Eve Kosofksy. “Swan in Love: The Example of Shakespeare’s Sonnets.” Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. New York: Columbia UP, 1985.28-48. Print.