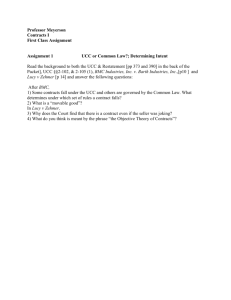

New Student Orientation Spring 2016 Packet

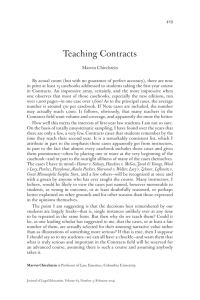

advertisement