Exchange Rates and International Monetary System

advertisement

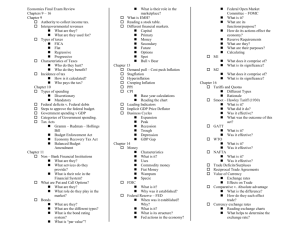

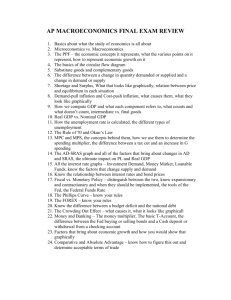

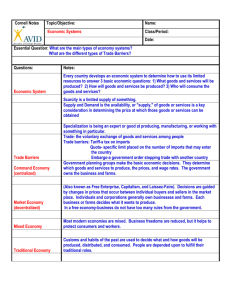

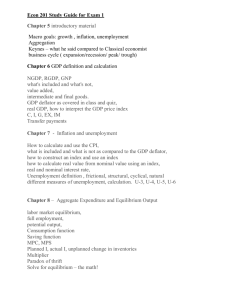

Exchange Rates and the International Monetary System Lecture by Neven Mates Outline • International economic relations • • • Trade flows (goods and services), income flows, grants Capital flows Balance of payments • Foreign exchange markets and the exchange rates • • Forex market, supply and demand Appreciation, depreciation, revaluation, and devaluation • The international monetary system • • • • Golden standard and the fixed exchange rate system Adjustment of an economy to balance of payments imbalances under the golden standard Floating system and the system of managed exchange rate The International Monetary Fund International economic relations • Economics often starts with a model of closed economy: No foreign trade, no capital flows. • But such simple models are misleading in the modern World. • In closed economy saving is always equal to investment, demand of equals domestic supply and production, capital cannot flow in or out of the country, and government has the option of captive finance. • Today all economies trade internationally large part of their output. • Moreover, countries have liberalized their capital account transactions and investors trade with financial assets. As a result, capital flows are much larger than the trade flows. Global trade grows faster than output: Economies are becoming more open - Globalization Global Trade and GDP 1980-2016 growth rates 20 15 10 % 5 19 80 19 84 19 88 19 92 19 96 20 00 20 04 20 08 20 12 20 16 0 -5 -10 -15 Trade volume of goods and services Gross domestic product, constant prices Year Degree of openness varies across countries Figure 7: Exports of Goods and Services 2008, as % GDP Serbia Romania Bosnia and Herzegovina Poland Latvia Croatia Bulgaria Lithuania Slovenia Estonia Czech Republic Hungary Slovak Republic Exports of Goods and Services, % GDP Croatia SEE Baltics Central Europe EU periphery Emerging Asia Emerging Latin America 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 Source: WB Database, IMF WEO September 2011 Database. *Data for groups calculated with weights corespondiong to nominal GDP in $ in 2008 Large economies are less open: Exports of goods and service to GDP • USA 2010 Eurozone: 12.6% 24.0% Export growth is a must for small open economies Figure 6: Exports of Goods and Services in 2010, 2000=100. Croatia Serbia Slovenia Latvia Bulgaria Bosnia and Poland Slovak Republic Estonia Hungary Romania Czech Republic Lithuania Export of Goods and Services Volume 2010, 2000=100 Croatia SEE Baltics Central Europe EU periphery Emerging Asia Emerging Latin America 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 Source: IMF WEO September 2011 Database. *Data for groups calculated with weights corespondiong to nominal GDP in $ in 2010 350 400 Conclusion: International trade • International trade is the main engine of global growth. • Growth of international trade persistently surpasses growth in global GDP. • Smaller an economy is, more it is dependent on international trade. • Small countries have to specialize. Capital flows are even larger • Exporting and importing countries have to settle their obligations, i.e. to make and receive payments. • But residents of various also trade with assets, i.e. they lend and borrow. • We will now focus on how these payments are accomplished. The balance of payments: • Presentation of all payments between residents of one country (households, financial and non-financial corporations, government) and the rest of the world (non-residents). • There is an important distinction between payments for current and for capital transactions. Balance of payments: I Current account • Residents of a country sell goods and services to non-residents and buy from them (exports and imports) • Residents also receive income from abroad from their investments and from labour services provided to non-residents. • On the other side, residents pay to non-residents for the use of foreign capital (loans, equity investments) and for their labour services. • Residents also receive and extend grants • All these transactions are called the current account transactions, as they represent incomes earned and costs incurred abroad. • The net outcome of all these transactions is called the external current account balance of a country. It is called deficit if negative. The current account balance (or deficit) • The current account balance= 1+2+3+4 • 1. Trade balance • Exports of goods minus imports of goods • 2. Balance of services Exports of services minus imports of services • 3. Income balance Investment income of residents (interest and dividends received) and received payments for labor services of residents minus such payments to nonresidents • 4. Balance of grants (unrequited transfers, remittances) The current account balance (or deficit) • If a country has a positive external current account balance, this means that its income is higher than its domestic absorption (consumption and investment). • This also means that its saving is higher than its domestic investment (fixed capital formation plus increase in inventories). • The surplus is used to acquire assets (invest) abroad. Balance of payments: II Capital account—Outward investments • Residents of a country make investments abroad: – Make deposits in foreign banks and extend loans to non-residents – Buy stocks and shares abroad (portfolio investments) – Directly invest in foreign companies (they invest in and acquire some control over a foreign company). Balance of payments: II Capital account—Inward investments • Non-residents make investments in the country: – Increase their deposits with the domestic banking sector – Extend loans to domestic banks, firms, household, government) – They buy stocks and shares (portfolio investments) – They directly invest in domestic companies (acquire controlling equity and extend loans to such companies). Balance of payments: II Capital account - net flows • Sum of all inflows and outflows of capital from financial transactions gives the capital account balance. Simplified: The capital account balance equals net borrowing abroad (borrowing minus repayment) minus net investments abroad. • The positive balance means that the country is receiving more capital from abroad than it has invested abroad. • The following identity holds: • I + II = 0 Balance of payments: Change in official reserves • It is often convenient to separate operations of the central bank from operations of other domestic residents. • Then the identity looks as follows: • I + II + III = 0 • where II is now capital transactions excluding the central bank, and • where III is the use of reserves of the central bank. If III is positive, this means that the central bank has reduced (i.e. sold) some of its reserves. Decline of reserves will be presented with a positive sign, and increase will be shown with a negative sign. Capital and financial account • Recently, the IMF introduced a new classification by splitting the capital account into capital account and financial account. • Capital account comprises capital grants and some other items: It is very small. • All important transactions are recorded in the financial account. • Most people ignore the new terminology, and just refer to the capital account. BoP: Errors and omissions • BoP tables are compiled from various sources: – Trade data are from custom statistics – Data on services are usually from banks and surveys – Capital transactions come from banks and surveys These data do not add up. The difference is shown as Errors and Omissions. In the following table for Croatia, the identity reads as: A +B1+ B2 + C= 0 where A is current account balance, B1 is capital account balance excluding movements in official reserves, B2 is change in official reserves, and C are errors and omissions. BoP Table for Croatia 2008-2010 Table H7: Balance of Payments - Summary in millions of EUR 2008 A. CURRENT ACCOUNT (1+6) 1. Goods, services, and income (2+5) 1.1. Credit 1.2. Debit 2. Goods and services (3+4) 2.1. Credit 2.2. Debit 3. Goods 3.1. Credit 3.2. Debit 4. Services 4.1. Credit 4.2. Debit 5. Income 5.1. Credit 5.2. Debit 6. Current transfers 6.1. Credit 6.2..Debit -4.196,7 -5.267,1 21.298,5 -26.565,7 -3.719,2 19.904,6 -23.623,8 -10.793,8 9.814,0 -20.607,8 7.074,6 10.090,6 -3.016,0 -1.548,0 1.393,9 -2.941,9 1.070,5 1.684,4 -613,9 2009** 2010** -2.379,7 -3.416,0 16.956,4 -20.372,4 -1.617,0 16.157,1 -17.774,1 -7.386,9 7.703,2 -15.090,1 5.769,9 8.453,9 -2.684,1 -1.798,9 799,4 -2.598,3 1.036,3 1.607,8 -571,5 -535,0 -1.622,9 18.487,3 -20.110,3 -65,5 17.591,8 -17.657,4 -5.952,0 9.102,3 -15.054,3 5.886,5 8.489,5 -2.603,0 -1.557,4 895,5 -2.452,9 1.088,0 1.684,6 -596,6 BoP Table for Croatia 2008-2010 B. CAPITAL AND FINANCIAL ACCOUNT B1. Capital account B2. Financial account, excl. reserves 1. Direct investment 1.1. Abroad 1.2. In Croatia 2. Portfolio investment 2.1. Assets 2.2. Liabilities 3. Financial derivatives 4. Other investment 4.1. Assets 4.2. Liabilities B3. Reserve Assets C. NET ERRORS AND OMISSIONS 5.772,4 14,9 5.427,1 3.246,0 -972,7 4.218,6 -810,1 -380,8 -429,2 0,0 2.991,2 -1.621,6 4.612,8 330,4 -1.575,7 3.431,0 43,1 4.284,3 1.491,7 -888,2 2.379,8 420,9 -558,1 979,1 0,0 2.371,7 748,0 1.623,8 -896,4 -1.051,3 1.264,2 34,5 1.313,5 393,1 112,3 280,9 397,1 -368,3 765,4 -252,7 776,0 697,5 78,5 -83,8 -729,3 The BoP Table for Croatia 20082010: Comments and questions • How important are services for Croatia’s BoP? • What happened to Croatia’s current account 2007-2010? • To the capital account? • To official reserves? • How large are the errors and omissions? Phases in the development of current account balances • • • • • • • Traditionally, it was assumed that developing countries would be importing capital, i.e. they would run current account deficits. Their investments would be higher than their savings. Mature, or advanced economies on the other hand would be running surpluses, i.e. have larger savings than investments. However, in the modern world this has changed. Germany, Japan and some other advanced economies indeed run current account surpluses as expected. So do oil producers. However, China and other emerging market economies in Asia have very high saving rates and run current account surpluses. On the other hand, advanced economies like US have low saving rates and run current account deficits. Southern eurozone countries, after euro was established, have cut down their saving rates, while some of them also increased unproductive investments. As a result, they started accumulating large foreign debts and are now in trouble. Their currencies appreciated in real terms and these countries became noncompetitive. CA imbalances Credit boom in Non-core eurozone How to make payments in the world of national currencies? • So far we have focused on transactions, but not how the corresponding payments are made. • Residents from different countries use different currencies. • How are these currencies exchanged? Exchange rates: Some definitions • Appreciation: Domestic currency gets stronger relative to a foreign currency. For example, one needs less kunas to buy euro. Depreciation is the opposite. • Be careful: “The exchange rate got higher” usually means that you need more domestic currency to buy foreign currency. This means that domestic currency has depreciated. • Revaluation: In fixed exchange rates systems, decisions to set the rate at a more appreciated level. The opposite is devaluation. Foreign exchange market-Selling side • Every day exporters sell their proceeds. • Those who borrow abroad and want to use these resources domestically, sell their $ and euros in the market • Foreigners who want to invest in Croatia sell $ or euros to buy kunas. • Foreign exchange market-Buying side • Importers • Residents who want to repay their debts in $ and euros, increase their deposits abroad, lend to non-residents, or acquire assets abroad. • Non-residents who want to repatriate their incomes and investments. Foreign exchange marketEquilibrium • In a fixed exchange rate system, the equilibrium is established by central bank interventions, i.e. by central bank purchases or sales in the forex market. • In a flexible exchange rate system, the equilibrium is established by price, i.e. by adjustment in the exchange rate. When supply of euros in the foreign exchange market is lower than demand, the price for euro gets higher, i.e. kuna depreciates. And vice versa. • Fluctuations are reduced by speculators (those who take short or long positions). They sell foreign currency when they consider that the kuna exchange rate has depreciated below equilibrium, and buy foreign currency when they see the kuna exchange rate as too low (to much appreciated). Exchange rates: Where do they settle in the long-run? • In the system of flexible exchange rate, the bilateral nominal exchange rates (for example $/yen) fluctuate a lot. • There are many factors driving the nominal ERs. For example: – Cyclical position of two countries: If Japan is in recession, it imports less, which should reduce demand for $, and lead to appreciation of yen. – However, since interest rates in Japan are low when its economy is in recession, and in the USA they are high if its economy is booming, this will increase demand for $, and lead to depreciation of yen. The second effect is in practice much stronger. Purchasing power parity (PPP): A theory on the equilibrium exchange rates • • • • • • PPP theory expects that the exchange rates will settle, or converge toward levels at which prices of tradable goods in two countries are equal. The rationale: Given the fact such goods can be traded across borders, disparities in prices can be eliminated by trade. If tradable goods at the current exchange rate were cheaper in Mexico than in USA, Mexico would export them to the USA. In a system of flexible exchange rates, this would lead to the appreciation of pesos until the parity is established. In a fixed exchange rate system, Mexican prices of exported goods will increase until the parity is established. This means that peso would appreciate in real terms, although nominal exchange rate would remain stable. However: Transportation costs and custom duties impose wedge between prices of the same good in different countries. Customers might also have domestic bias. Purchasing power parity—Two Implications • 1. If a country is experiencing high inflation, then its currency will depreciate relative to the country with a stable price level. However, with the disappearance of inflation as a global problem, this factor has lost on importance. • 2. How to compare GDP in different countries? Take note that the equality of prices under PPP theory applies only to tradable goods. This has interesting implications for measuring GDP. Assuming that USA has much higher level of productivity in production of tradable goods and services. Other things equal, this will imply that wages in those sectors are much higher in the USA than in China. Let us also assume that wages in non-tradable sectors in both China and USA are equal to wages in their tradable sectors. As a result, wages in China-s non-tradable sector are much lower than in the USA, regardless of productivity in non-tradable sectors. China prices for non-tradable services and goods will therefore be much lower in China. One $ will therefore buy a larger consumer basket in China than in the USA. This means that China’s GDP calculated at nominal exchange rate in $ would be underestimated as a measure of well-being. When nominal GDP is corrected for purchasing power, one gets GDP at PPP. • • • • • • GDP PPP Adjusted, in billion $ Table: GDP at nominal and PPP adjusted echange rates, 2010 GDP GDP PPP Ratio China 5878 10120 1,7 Germany 3286 2944 0,9 India 1632 4058 2,5 Japan 5459 4324 0,8 United Kingdom 2250 2181 1,0 United States 14527 14527 1,0 Source: IMF WEO, 2011. GDP and GDP PPP Adjusted 2010 16000 14000 12000 10000 GDP GDP PPP 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 China Germany India Japan United Kingdom United States Summary on exchange rates: • In today’s world, movements in the exchange rates are difficult to predict. • Interest rates and expectations about their movements do affect exchange rates. • But it was not always so. Global monetary system • System of fixed exchange rates: Global golden standard • System of flexible exchange rates • System of managed exchange rates Golden standard • Between early 18th century and 1930s, with some interruptions, monetary system of all major global economies was based on gold: Gold (coins and bullion) were the main medium of exchange in international trade. Domestically, banknotes were exchangable for gold. • Coins of different nations contained different quantity (weight) of gold. • Their exchange rates were determined by the ratio of quantity of gold they contained. Golden standard: Macroeconomic adjustment • English philosopher Hume described how prices and incomes adjust under the golden standard (1752) • He assumed that the level of prices depends on supply of money in the country. • If US wages and prices increase above equilibrium, US would import more from UK than it would export. • Therefore, it would be losing gold. • The reduced quantity of gold would push prices and wages in the US down. The increased quantity of gold in UK would push the prices up. This would correct prices and the trade flows. • If gold is found in California, this would trigger inflation in the USA and the UK. In the early 20th century, the golden standard came under pressure • Some countries during the WW I de-linked their currencies from gold. • After the war, some tried to re-establish the old parity: The result was a long depression. This suggested that the golden standard was too inflexible. • Then, during the 1930s depression, some countries again de-linked their currencies from gold and devalued them. • This was seen by others as unfair competition (“beggar your neighbour policy”). • In response, they strengthened protectionist policies: higher custom protection, and restrictions on payments for imports. • The result was a further drop in global trade, which exacerbated the recession. • After the WW II, these issues tried to be addressed by establishing the IMF. The fixed but adjustable system under the Bretton-Woods agreement 1945 • Post WW II global monetary system was designed by victorious coalition at the conference in Bretton Woods USA in 1944. • To facilitate global trade but also to prevent competitive devaluations, the international monetary system it was decided to base global monetary system on fixed but adjustable exchange rates. • The anchor to the system was still provided by gold, or by $ which was fixed to gold. • The exchange rates could however be adjusted only with the approval of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). • At the same time, to reduce the need and magnitude of adjustments in the exchange rates, the IMF would provide loans to countries that have run out of their golden reserves. • These countries would have to reduce their consumption so as to bring their balance of payments into equilibrium. The breakdown of the Bretton-Woods System • The fixed but adjustable system of exchange rates was designed at the time when capital flows were small. • The balance of payment pressures were driven primarily by external current account flows. This means they were limited in scope and not developing fast. • However, with growing liberalization of capital flows, the system of the fixed exchange rates became unsustainable. • Imbalances started to become larger, and grew faster. • When the US in late 1960s followed expansionary fiscal and monetary policies (printing too much $), US started losing gold reserves, and eventually had to abandon the convertibility of $ into gold in 1971. The system fell apart. • Since then, major economies float their currencies (US, UK, Euro zone, Canada, Australia, Sweden, Japan), some of them with occasional interventions by their central banks). Small countries with fixed exchange rates after 1972 • After large countries let their currencies float, some small countries continued to fix their exchange rates to currencies of their major trading partners. • Under the currency board arrangement, the central bank creates domestic currency only by buying foreign currency at fixed exchange rate. It is always willing to sell or buy foreign currency at the same rate. No domestic central bank money is created by credit. As a result, all primary money is fully covered by official reserves of the central bank. • Other countries fix their exchange by announcements, or practice of their central banks. Their central banks continue to extend credit, but usually do not have much scope to do it. Small countries with floated or managed exchange rates after 1972 • Other countries have flexible exchange rates with occasional interventions (interventions are purchases and sales of foreign currency by the central bank). • Interventions are used only to smooth large fluctuations, or to keep the exchange rate within some band, which may or not be announced. • Interest rates of central bank might also be adjusted with a view of keeping the exchange rate within some range. Such systems are called managed exchange rate systems. • Some countries operate in inflation targeting framework. They use only interest rate policy so as to target low inflation, but usually abstain from foreign exchange rate interventions. Macroeconomic adjustments in different exchange rate systems • In fixed exchange rate systems, the adjustment is similar to the one described by Hume, except that countries with the deficits in the BoP now lose official reserves, instead of gold. • Loss of reserves results in tightening of domestic monetary conditions and this reduces domestic consumption and investment. • In floating systems, BoP pressures result in depreciation. To prevent inflation, the central bank has to increase its interest rate. Macroeconomics of small open economies • Small economy: One that cannot influence global prices • Open economy: It is engaged in foreign trade, and can run current account deficit or surplus. • What are the main implications? Macroeconomics of small open economies • Effect on multiplier • Effect on investment-saving balance Simple Keynesian model of a closed economy without income taxes This mechanism can best be described by the following simple model of a closed economy. We assume here that government does not collect income or consumption based taxes, and that there is spare capacity in the economy: C= a + bY Y=C+G+I By combining these two equations, we get Y = (a+I+G)/(1-b) If there is no free capacity in the economy, an increase in G would have to squeeze out investment or private consumption. It is usually assumed that this would take place via increases in interest rate. As the government tries to borrow funds to increase its spending, this increases the interest rates, which then reduces private investment. If spare capacity is available, an increase in G results in an increase in output Y. dY/dG = 1 / (1-b) fiscal multiplier If the b is equal to 0,80 then the multiplier is 5. 48 Simple Keynesian model of a closed economy without income taxes The above results can also be demonstrated with the following figure: C+I+G’ C, I, G C+I+G Y Y’ Y Increasing G and assuming spare capacity would therefore increase aggregate demand, which means that the line C+I+G would be shifted up by the corresponding amount. Output would then increase from Y to Y'. 49 Simple model with income taxes Model with income tax: Yd=Y-tY C=a+bYd Y=C+I+G, Combining equations we get: dY/dG = 1/(1-b(1-t)) Assuming b=0.8, and t=0.3, results in much lower multiplier of about 2.3 Income tax would therefore reduce the value of the multiplier, but the multiplier would still remain larger than 1. Such simple models suggest that in situation with spare capacity, an increase in government spending produces substantially larger increase in GDP. On the basis of such reasoning, the following policy prescription follows: When economy is in recession, government should increase spending (or reduce taxes) to provide stimulus to the economy, and smooth the output path. Fiscal policy appears in such models as a powerful tool. 50 Simple model with income taxes Model with income tax: Yd=Y-tY C=a+bYd Y=C+I+G, Combining equations we get: dY/dG = 1/(1-b(1-t)) Assuming b=0.8, and t=0.3, results in much lower multiplier of about 2.3 Income tax would therefore reduce the value of the multiplier, but the multiplier would still remain larger than 1. Such simple models suggest that in situation with spare capacity, an increase in government spending produces substantially larger increase in GDP. On the basis of such reasoning, the following policy prescription follows: When economy is in recession, government should increase spending (or reduce taxes) to provide stimulus to the economy, and smooth the output path. Fiscal policy appears in such models as a powerful tool. 51 Model with imports Let us assume that the economy also imports, and that demand for imports M is proportional to income. Exports E are determined exogenously. M=mY+n Yd=Y-tY, C=a+bYd, Y=C+I+G+E-M, which results in Y= a+(b(1-t))Y+I+G+E-mY The multiplier in such situation is given by dY/dG = 1 / (1-b +bt+m) Assuming elasticity of imports to income of 0.7 (which is often used for small open economies), b equal to 0.8 and t equal to 0.3, gives a substantially lower multiplier of 0.9. Such result follows from the fact that the increased domestic demand not only affects domestic production, but it also leaks into imports. 52 Limitations of simple models The household consumption function in this model is extremely simple, linking consumption only to the current income. More realistically, consumption is linked to permanent income (expected income over an extended prospective period). As a result, the secondary effects of government spending, i.e. the multiplier are lower. The multiplier is much lower in an open economy simply because part of additional demand leaks into the current account balance. Households may react to the increases in government spending by reducing their own spending in expectations that government will have to increase taxes in the future. Such behaviour is called Ricardian. To keep their future spending path unchanged, in response to government's decision to increase spending, households immediately increase their saving, offsetting the effect of higher government spending. . 53 Limitations of simple models There are, however, also other explanations why households might react negatively to the increase in government spending. For example, in a country that has been plagued by large budget deficits and high inflation, government's decision to further relax budget in a situation when the government is already facing risk of default, might result in consumers' and investors' loss of confidence, and reduction in their spending. In the opposite case, announced cuts in budget spending might improve consumer and investor confidence, and result in increased private sector spending and investment. The effects of such changes in the private sector behavior might be larger than the direct effects of increased budget spending. Fiscal consolidation might in such circumstances be expansionary, while fiscal expansion might be contractionary. 54 Empirical results In a recent study, the IMF staff estimated that the multipliers for government investment amount to 1-1.5 in large countries, 0.5-1 in middle size countries, and 0.5 in small countries. The multipliers are much smaller for government transfers and tax cuts. Moreover, they pointed out that the multipliers could indeed be negative if the country faces problems with fiscal sustainability Conclusions: While in simple models of closed economy fiscal policy appears to be a very effective instrument to fight recession, the picture drastically changes when one considers more complicated models. Moreover, empirical results also suggest that the power of fiscal policy is much more moderate. 55 Saving-investment balance in a closed economy • • • • Sp = Ip + G + Ig – T Sg = T – G - Ig Sp + Sg = Ip + Ig S=I • Domestic interest rate establishes equilibrium between investment and saving Saving-investment balance in an open economy • National savings equal investment plus current account balance • S = I + CA The influence of the budget deficit on the external current account deficit Identities below decompose national net savings into private sector net savings (private savings minus private investment) and government net savings. GDP=C+I+G+X-M (GDP from the expenditure/absorption side) Sg = NT-G (Government savings equals net taxes (taxes - transfers) minus government consumption. It is also equal to the budget operating surplus) NSg = Sg - Ig=GB (net savings of the government equal government savings minus government net investment, which is equal to the government balance) Sp = GDP + NFI - C - NZ (Private sector savings equal income from producing GDP plus net factor incomes from abroad minus private consumption minus net taxes) S = Sg+Sp (Total national savings are the sum of private and public savings) CA = X-M+NFI (Current account balance equals exports of goods and services minus imports plus net factor incomes from abroad). 58 The influence of the budget deficit on the external current account deficit Combining all identities, we get: CA = S - I = Sg + Sp - Ig - Ip = NSg + NSp = GB + NSp (Current account balance CA equals government balance GB plus private sector net savings NSp) This identity tells us that the external current account balance is equal to the budget balance plus private sector saving-investment balance. This does not mean that the two private S-I balance and the budget balance move completely independently, so that for example by improving the budget balances by 1 percent of GDP, the current account automatically improves by the same amount. Recent empirical research suggests that the elasticity of the current account balance to the budget balance in medium-term is about 0.3-0.5, while it is higher in the longer term. The budget deficit therefore affects the external current account deficit. Excessive current account imbalances are these days seen as an important indicator of external vulnerability of a country. 59 The role of interest rates in closed and open economy • In a closed economy, equality of I and S is established via interest rates. • In an open economy, the global interest rate is exogenously given. • The global interest rate (plus country’s risk spread) will determine, combined with other factors, I and S. If investment is higher than S, the country will borrow abroad. • See charts in Samuelson’s Economics.