5Amy

advertisement

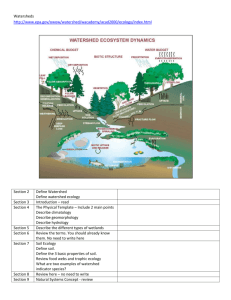

Amy Forsgren WLF 501 Introduction and Background Community based conservation (CBC) is based on the idea that locals and indigenous communities should be actors in the management of natural resources (Fisher, 2001). It seeks to link conservation with sustainable development and the protection of biodiversity and natural landscapes with the protection of traditional indigenous groups and cultures (Igoe, 2006). CBC came about several decades ago in response to authoritarian practices that ignored the rights of local communities and often forced groups to people to relocated, resulting in hardship and distrust for many people (Chicchón, 2009) as well as ignoring that humans for centuries have been a significant part of the landscape (Mann, 2005). CBC approach heavily emphasizes the inclusion of local and traditional knowledge. This has lead to implementing programs in areas such as the Kaa-lya del Gran Chaco National Park in Bolivia, where education programs and a highly involved collaborative effort have been implemented to protect the resource. Indigenous groups offered native knowledge of plants and resources in the region and reportedly achieved a successful conservation rates (Beltran, 2000). CBC asserts that many traditional practices are considered sustainable and ecologically friendly (Wilshusen et al., 2002). It also allows locals living in the area to help maintain the natural systems that they depend on and access daily. However, these assumptions have caused some problems in that they assume that traditional practices are sustainable, which may not always be the case and asserts that local and indigenous groups have the best interests of the resource at heart (Igoe, 2006; Wilshusen et al., 2002). These assumptions and lack of funds, lack of trust between stakeholders, and lack of or only token acknowledgement of local and traditional rights and needs in the area are many reasons why Community-based management produced few successful results (Fisher, 2001). Another issue that questions the decentralizing and community approach of CBC is political ecology theory. Political ecology seeks explain the complexities of interplay between society and natural resources, as well as interactions between groups within society (Blaikie & Brookfeild, 1987 as referred to in Robbins, 2005). This theory addresses environmental concerns from multiple levels, i.e. local, regional, and global. It covers scales of power and authority from local indigenous groups to international organizations and governing bodies (Robbins, 2005). Political ecology shifts the idea of human dimensions of environmental change from homogenous communities, dependant on local rules and regulations for resource use and access, to a web of actors using the resource in different ways, with varied access to control and power (Nygren & Rikoon, 2008). This is demonstrated by Zimmerer (2000). Looking at irrigation in the Cochabama region of Bolivia, Zimmerer notes that although may places have taken up a community-based approach to water management, historically, irrigation had been developed in this region to accommodate large-scale farming and adverse geographical and ecological conditions that canal-based management is not necessarily equipped to handle. Because of canal-based management widespread implementation in the region, irrigation has become difficult to organize, leaving certain farmers without access to water. Zimmerer (2000) suggests that community-based irrigation was not a natural phenomenon or a practical social solution. The failure of many CBC attempts can be attributed to its inability to account for multiple stakeholders and varied scales involved environmental resources (Berkes, 2004). Currently, a number of collaborative efforts are being experimentally implemented to try to find the correct solution to environmental degradation and conflicts over conservation among stakeholders at various scales. For example encouraging the use of traditional privately owned common property that can be used for multiple types of resource use in Mexico, offering necessary habitat for keystone species (Bray and Velazquez, 2009). These attempts have lead to the acknowledgement that no program or process should be put into affect without first understanding the local social phenomena (Berkes, 2004; Peterson et al., 2010; Zimmerer, 2000). In addition, understanding how systems currently function may uncover important cultural practices that should be considered in management plans, also, reinforcing trust and local participation in new management practices. The goal of this project is two-fold: to understand the cultural perceptions of the high Andean watersheds and, most importantly, identify any traditional management practices that might be used in Municipal watershed management plan. Research Question: Is there a form of sustainable traditional management practices already in place that could be included in a management plan for the Yacuambi river basin? Sub Questions: What is the social understanding, or meaning, of the watershed to people living in the Yacuambi River Basin Area? What are peoples’ uses of water? Are people concerned with the water? What do they see as a problem or not as a problem? What do people think solutions to watershed problems should be? Who should solve them? Who are the primary stakeholders in this watershed area? Literature Review Political intervention in water management is currently shifting in two directions, upward toward the national or supranational and downward toward the regional or local scale (Moss & Newig, 2010). For Ecuador, this intervention is primarily the latter, with locals becoming increasingly more involved with water management (Boelens & Doornbos, 2001; Garcia & Brown, 2009) Depending on the social and ecological considerations, a local self-management approach to water policies may be appropriate, but with the current broad issues of climate change and multiple uses across political boundaries, it may not always be the best solution (Moss & Newit, 2010). The Yacuambi Wetlands seeks to take a local approach, therefore, understanding the current forces in play is necessary to protect the wetlands. Studies conducted nearby Yacuambi and in similar protected area in South America, have uncovered complications dealing with interactions between social and ecological aspects. Many Protected Areas are designated with the desire to protect critical habitats and watersheds, but data used to examine these areas was often disparate and inaccurate regarding human occupation and land use, which has partly created a disparity between land use and legal status on paper. In addition, there are few, if any, areas of empty wilderness that do not have to account for human interaction with the natural environment (Naughton-Treves, et al., 2006). Podocarpus National Park, a protected area just south of Yacuambi, struggles to mediate between necessary human activities and protection of the resource. Interests vary between key stakeholders and there is little coordination between actors, such as NGO’s and tour operations, in the Podocarpus community. The result is that many activities are in practice on the ground that are not legally accounted for on paper (Clark, et al., 2009). Given the small amount of support by local actors, Clark, et al. purports that successful management cannot be achieved until individuals and institutions enter into the management decision-making process that combines diverse interests with common goals. The same need for an effective management decision-making process was found to be true in the Condor Bioreserve in Ecuador, as well (Ziegelmayer, Clark, & Nyce, 2004). Those affected most by the implementation of protected areas are those who depend on it for their livelihood (Saelemyr, 2004). Rural communities see protected areas as an obstacle to daily living rather than a way to protect resources that they are dependant upon. In general, they do not see the park in terms of aesthetic value but rather as a resource for daily living (Saelemyr, 2004). It is possible that many in the Yacuambi valley may share these same sentiments. Protected areas provide many economic as well as ecological benefits, such as watershed protection, forest products and biodiversity. Different management approaches will provide different benefits at different scales: local, regional or global. Therefore, the first step in a collaborative protected area is to determine the costs and benefits at each scale by understanding key stakeholders, such as landowners, scientists, local communities, and NGOs. Each stakeholder will have different motivations for protecting the areas and therefore play different roles in the protected area (McNeely, 2001). Conflicts over conservation and resource use, as well as their allocations are deeply rooted in culture. Local/indigenous groups view the natural world as the source of their life, both economically and culturally. It offers spaces, material, and means for cultural identity, and sustenance for life (Peterson et al., 2010). References: Beltran, J. (Ed.) (2000). Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and integrated management natural area, Boliva. Indigenous and traditional peoples and protected areas: Principles, guidelines and case studies. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK and WWF International, Gland, Switzerland. 29-39. Berkes, F. (2004). Rethinking community-based conservation. Conservation Biology, 18(3), 621-630. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2004.00077.x. Boelens, R., & Doornbos, B. (2001). The Battle of water rights: Rule making amidst conflicting normative frameworks in the Ecuadorian highlands. Human Organization 60(4), 343- 355. Bray, D. B., & Velazquez, A. (2009). From Displacement-based Conservation to Placebased Conservation. Conservation and Society, 7(1), 11-14. Chicchón, A. (2009). Working with Indigenous Peoples to Conserve Nature: Examples from Latin America. Conservation and Society, 7(1), 15-20. Clark, S. G., Cherney D. N., Ines A., Bernardi De Leon, R., Moran-Cahusac, C., (2009). A Problem-oriented overview of management policy for Podocarpus National Park, Ecuador. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 28, 663-679. doi:[10.1080/10549810902936243] Fisher, R. J. (2001). Experiences, challenges, and prospects for collaborative management of protected areas: An international perspective. In L. Buck, C. Geisler, J. Shelhas & E. Wollenberg (Eds.), Biological diversity: Balancing interests through adaptive collaborative management (pp. 81-96). Boca Raton: CRC Press. Garcia, R., & Brown, S. (2009). Assessing water use and quality through participatory research in a rural Andean watershed. Journal of Environmental Management, 90, 30473047. López-Rodiguez, F.V. (2010). Propuesta para la conservación de los humedales Tres Lagunas, Laguna Grande y Condorcillo y los ecosistemas adyacentes localizados en Oña, Nabón, Saraguro y Yacuambi en el sur del Ecuador. Universidad técnica particular de Loja. Unpublished report. Mann, C. C. (2005). 1491: New revelations of the Americas before Columbus. New York: Knopf. McNeely, J. (2001). Roles for civil society in protected area management: A Global perspective on current trends in collaborative management. In L. Buck, C. Geisler, J. Shelhas & E. Wollenberg (Eds.), Biological diversity: Balancing interests through adaptive collaborative management (pp. 27-49). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Moss, T., & Newig, J. (2010). Multilevel water governance and problems of scale: Setting the stage for a broader debate. Environmental mangement, 46, 1-6. Naughton-Treves, L., Alvarez-Berrios N., Brandon, K., Bruner A., Holland, M., Ponce, C., Saenz M., Suarez, L., & Treves, A. (2006). Expanding protected areas and incorporating human resource use: A study of 15 forest parks in Ecuador and Peru. Sustainability: Science, practice, & policy, 2(2), 32-44. Retrieved September 15, 2010 from http://ejournal.nbii.org Naughton-Treves, L., Holland, M., & Brandon, K. (2005). The role of protected areas in conserving biodiversity and sustaining local livelihoods. Annual review of environment and resources 30, 219-252. Neumann, R. P. (2005). Making political ecology. Human geography in the making. London: Hodder Arnold. Nygren, A., & Rikoon, S. (2008). Political Ecology Revisited: Integration of Politics and Ecology Does Matter. Society & Natural Resources, 21(9), 767-782. doi:10.1080/08941920801961057. Ravnborg, M., (2010). Oganising to protect: Protecting landscapes and livelihoods in the Nicaraguan hillsides. Conservation and Society 6(4) 283-292. dio:10.4103/09724923.49192 Rikoon, J. (2006). Wild horses and the political ecology of nature restoration in the Missouri Ozarks. Geoforum 37(2), 200-211. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2005.01.010 Robbins, P. (2004). Political ecology: A critical introduction. Critical introductions to geography. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. Saelemyr, S. (2004). People, park, and plant use: Perceptions and use of Andean ‘Nature’ in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. Journal of Geography, 58, 194-203. Wilshusen, P. R., Brechin, S. R., Fortwangler, C. L., West, P. C., (2002) Reinventing the square wheel: Critique of a resurgent “protection paradigm” in international biodiversity conservation. Society and Natural Resources 15:17-40. Ziegelmayer, K., Clark, T.W., & Nyce, C. (2004). Biodiversity and watershed management in the Condore Bioreserve, Ecuador: An analysis and recommendations. Journal of Sustainable Forestry, 18(2-3), 139-170. Zimmerer, K. (2000). Rescaling irrigation in Latin America: The cultural images and political ecology of water resources. Ecumene, 7(2), 150-175. Retrieved from Academic Search Premier database.