A Brand Building Literature Review

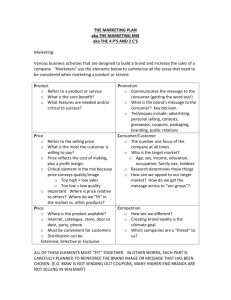

advertisement