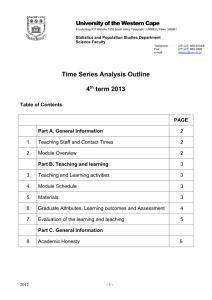

Unit 2 - University of the Western Cape

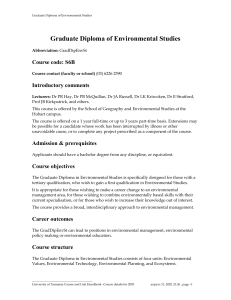

advertisement