Life of Pi Analysis: Genre, Storytelling, and Religious Belief

advertisement

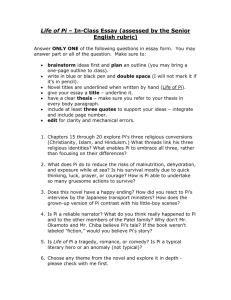

Life of Pi By Yann Martel Is Martel trying to “bamboozle” us? Does making sense of Life of Pi seem a bit like making sense of this Escher print? “The finite within the infinite, the infinite within the finite.” Using Escher as way to think about Life of Pi... Focus in on each individual part. What could each part mean of itself? What could it symbolise? What are the similarities between parts? By associating commonalities we start to get a sense of the overall intent of the print. Most importantly, what are the points of difference? What is interesting about these differences? What do we notice when we stop trying to make sense of the print? Life of Pi can be classified as: • postcolonial novel, because of its post-Independence Indian setting as well as its Canadian authorship • a work of magical realism, because fantastical elements—such as animals with human personalities or an island with cannibalistic trees—appear in an otherwise realistic setting • a bildungsroman, a comingof-age tale • an adventure story • It even flirts with nonfiction genres – the Author's Note claims that the story of Pi is a true story that the author heard while backpacking through Pondicherry – and the novel, with its firstperson narrator, is structured as a memoir – at the end of the novel, look for interview transcripts, another genre of nonfiction writing A Castaway story • Story of survival ‘against the odds’, usually nature, own psyche and unexpected foes. • Expects characters to be creative with their resources and own abilities to cope in the new, unfamiliar environment. • • Stripped of the conventions which dictate behaviour and actions in civilised society. • Traditionally has a happy ending – being saved. LoP the Author tells us on p.93: “This story has a happy ending.” • Characters enlightened upon return to civilisation, their experiences offering them a new understanding of the world and themselves. Allegory • A symbolic fictional narrative that conveys a meaning not explicitly set forth in the narrative. • Allegory ...may have meaning on two or more levels that the reader can understand only through an interpretive process. • Literary allegories typically describe situations and events or express abstract ideas in terms of material objects, persons, and actions. What do you think? • Is it a hybrid of these and more? • Does it matter that the novel is indefinable in terms of genre? • Does this affect or enhance the story? • What might Martel be trying to achieve by using this stylistic approach to his novel? The Importance of Storytelling A story within a story within a story • The novel is framed by a (fictional) note from the author who describes how he first came to hear the fantastic tale of Piscine Molitor Patel. • Within the framework of Martel's narration is Pi's fantastical first-person account of life on the open sea, which forms the bulk of the book. • At the end of the novel, a transcript taken from an interrogation of Pi reveals the possible “true” story within that story. Storytelling is also a means of survival. The Nature of Religious Belief • Life of Pi begins with an old man in Pondicherry who tells the narrator, “I have a story that will make you believe in God.” • Storytelling and religious belief are two closely linked ideas in the novel. – each of Pi's three religions, Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam, come with its own set of tales and fables, which are used to spread the teachings and illustrate the beliefs of the faith. • Stories and religious beliefs are also linked in Life of Pi because Pi asserts that both require faith on the part of the listener or devotee Stories within Life of Pi • • • • • • • • • • • • Martel tells his own story about going to India to write a book. Martel refers to the story he was trying to write set in Portugal in 1939. Mr. Adirubasamy begins to tell the story of Pi Patel. Mr. Martel tells the story of meeting Pi Patel and continues to narrate this story as Pi Patel tells his story. Pi Patel begins telling his story. Pi Patel refers to the story of Christ in Gethsemane. Pi Patel refers to the Ramayana. Pi Patel refers to the Christian story of God’s sacrifice of his son. Pi Patel refers to the story of Lord Krishna and the milkmaids. Pi Patel refers to the story of baby Krishna accused of eating dirt. Pi Patel refers to the story of Vishnu incarnated as Vamana the dwarf. Pi Patel refers to the story of Rama’s struggle to get Sita. Narrative Structure The framework that provides the order and way in which a story is told. Narrative Voice • The novel is written in first person but, interestingly, has two distinct narrators in print. • Pi is one narrator, the Author is the other. • Their voices are clearly distinguished by the fonts used – the Author’s narration is distinguishable from Pi’s because it is italicised – making the reader’s journey through the double narrative easier to follow. • The time and setting of the Author’s narration are also different to Pi’s - set in Toronto after Pi’s rescue. • But who else tells the story? • The forms the narration takes also vary in each section. • Section one has both narrators communicating with the audience. • Pi’s ‘voice’ is that of a storyteller, with the luxury of fully expressing ideas and action, and developing characters, from within the narrative. • The Author’s voice, on the other hand, is that of the observer who stands apart from the story. He is reflective, commenting on his observations of Pi and his life in Toronto. • Section three is presented as a transcript and report, both usually non-fiction forms of writing. Martel blends these non-fiction forms so they can function as a narrative ‘truths’ within the novel. Structure • youtube/ Enotes/ LoP summary (watch on Friday when I’m away) • Four sections: Parts one, two and three, plus the Author’s narrative • Two possible stories Structure It is important to understand: • how these parts function, both independently and as a whole; • why you think Martel has included them – what is their purpose? • THEN, to develop your own ‘theories’ about what they mean to the overall story. Section 1- Toronto and Pondicherry pp.3-93 • Establishes Pi as a character. • What do we know about him? Write a list of the first 15 things that come to mind. • What defining human qualities do you think he possesses at this point? • Introduces faith as a life philosophy for Pi. • “That which sustains the universe beyond thought and language, and that which is at the core of us and struggles for expression.” p.49 • “Bapu Gandhi said, ‘All religions are true.’ I just want to love God...”p. 69 • Establishes the tensions and similarities between religion and science, and the religions of Hinduism, Christianity and Islam. • Foreshadows the ominous events to come through the interspersion of Author’s narrative. • Helps us understand the magnitude of section 2 to Pi’s life because we are familiar with what he has lost. • Enables Martel to embody Pi with skills and knowledge which will help him to survive in section 2. • Sets up the events which lead to the castaway storyline in section 2. • Is a story of itself – the story of Pi’s childhood. Section 2 – The Pacific Ocean pp.97286 • Abrupt opening – “The ship sank.” p.97- leading directly to the castaway storyline; the quest to survive. “To be a castaway is to be perpetually at the centre of a circle.” p. 215 • Laden with sensual imagery and symbolism. “Everything was screaming: the sea, the wind, my heart.” p.97 • Confined setting on the lifeboat leads to focus on minutiae and, thus, richer description of the details and significance of individual entities and experiences. • “It was a cockroach... It deployed its wings, rose in the air with a minute clattering, hovered...and then veered overboard to its death. Now we were two.” p.170 • Allows audience to come to know Pi when he is forced by circumstances to question what he believes, and what he had believed he was capable of. “I am who I am.” • Offers the sea journey, which parallels the life journey we must all experience, which is fraught with difficulty. • “Always the bitter emotion of hope raised and dashed.” p.199. Section 3 – Benito Juarez Infirmary, Tomatlan, Mexico • This section is mostly dialogue between Mr. Okamoto, Mr. Chiba and Pi. How is dialogue different to prose in the impact it has on the audience? • There is a great deal of humour about the bungling of their trip from the US to Mexico. Does their journey in any way parallel Pi’s journey? • This is the section where we learn the other version of the story we read in section 2. “So you want another story?” • In a typical narrative structure, after all of the conflict points are resolved we expect the final chapters to deliver the denouement – the final resolution or clarification of the plot. • Instead, we get another story, one which confounds and compromises our understanding of what we have previously read. • Here Martel is proving his point about the power of storytelling: that he, as the author, made you believe his original story about Pi’s journey at sea even though the second story suggests it unlikely to be true. The other story • What is the purpose of this story? • How does it change our understanding of what we have read in sections 1 & 2? • How does it relate to the idea of the “better story”? The message about storytelling • “I know what you want. You want a story that won’t surprise you. That will confirm what you already know. That won’t make you see higher or further or differently. You want a flat story. An immobile story. You want dry, yeastless factuality.” • Has Martel changed your mind about what a story should be? “Doesn’t that make life a story?” • The ending of the novel is a place you can go to in order to inform your conclusion. • Chapter 100 is predominantly in the form of a report, a piece of writing which should be pure “dry, yeastless factuality” but it ends with an aside, a personal reflection on the part of Mr. Okamoto. • Read the final paragraph. As the final words of the novel, what message do you think they convey? • Which Story in the novel do you believe in? Is there a RIGHT answer??