US/China Steel Policy (MS Word format)

advertisement

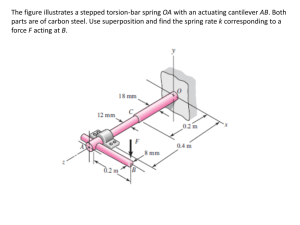

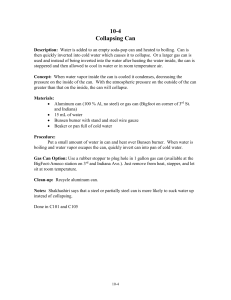

U.S./China Steel Policy A look into the trade policies of the U.S. towards China Mike Polefrone Mario Halasa Kyle Whittaker 11/29/2010 We looked at the trade policies between the U.S. and China steel industry with emphasis and due diligence put on the Bush steel tariffs implemented during the years of 2002-2003. This paper will try to provide insight on the effects that the tariffs had on both the United States economy and its citizens… Table of Contents I) Introduction II) History of Trade Flows and Policy III) Current Trade Patterns and Partners (And Current Patterns by Major Country) IV) Current Trade Policy V) Policy Evaluation VI) Recommendation VII) Graphs VIII) Works Cited 2|Page Introduction: For our trade policy brief we decided to analyze the steel industry of the United States and how it has been impacted through the use of tariffs and quotas and various other trade policies that led to the rise of foreign dependence on Chinese steel. We chose to look specifically at the impact on the United States through the past 20 years or so while focusing on the Bush steel tax reforms. By doing this we will be able to develop some further understanding on how the Bush steel plan impacted U.S. imports of steel and how it drove the United States to becoming an import driven steel economy. Since WWII the United States has implemented various policies and can be considered one of the “first movers” in setting up a system of world trade and world trading partners. They did so by implementing tariffs and quotas to try to balance and give some protection to the United States’ most precious industries. One of the top performers and profit drivers of U.S. industry is the steel industry. By implementing antidumping and many tariff restrictions on imports of foreign steel, it helped to protect the U.S. steel industry for a short period of time. Eventually the tariffs and quotas would be rewritten to compliment new trends or technologies which turned the steel industry into an unstable source of income for the U.S. Recently China has the largest bilateral trade surplus with the United States. When looking at the past years of trading numbers, China was only the eighth largest U.S. trading partner and was the source of nearly 3.5% of U.S. imports in 1996. By 2003 China had a 9.4% share in U.S. imports and was considered the third largest source of U.S. imports (cia.gov/china). As for U.S. steel industry, it has been protected for decades; The Institute of International Economics reports that from 1964 to 2001 U.S. steel consumption decreased by approximately 11%, while traditional steel production declined 54% (Liebman 2007). With respect to labor 3|Page patterns, more than 12.8 million Americans are employed in industries that are downstream consumers of steel, such as autos and appliances, yet only 170,000 workers are employed in the U.S. steel industry, a ratio of 57 to 1. With these competing outcomes and imbalances, steel firms are still the recipients of a high level of trade protection relative to other industries in the U.S. (Liebman 2007). Most recently in March of 2001-2002 President Bush announced measures to further protect the domestic steel industry from import competition. Bush re-imposed a 40% tariff on steel imports from foreign countries (Lee). This would lead to other nations cutting their steel production while allowing the U.S. to maintain their efficient level of production. Being that China today is the largest importer and 4th largest exporter of steel; the hypothetical tariffs and policies towards Chinese imported steel have had drastic effects on the United States abilities to produce at an efficient level coinciding with domestic consumer demands. Overall the intention of the program was to revitalize the steel industry in the United States. The effects of the first year of the program imposed 30% tariffs on imported steel from the biggest competitors of the American steel mills. Some other steel products faced tariffs that were in the range of 13-30% (Carbaugh 12th ed.). As a result of these protection clauses President Bush tried to push it on the steel companies to reduce their labor costs and invest in new technologies. The Bush steel tariffs did provide some relief to U.S. steel manufacturers but they did anger numerous steel “using” companies, such as automobile manufacturers. Those companies saw the effects of the tariffs by an increase in their costs and ultimately affected their labor force. Some tariffs are still in effect today other than the ones that were imposed by Bush in 2002-2003. Government trade regulators did vote however to revoke some of the restrictions on 4|Page steel trade based off of the arguments made by the automobile companies that they would become more profitable if there were a lower tariff on steel. With the elimination of some tariffs it would make the automobile market for competitive by reducing the key raw material needed to produce cars. The steel tariffs have played an integral part in the formation and welfare of the economy of the United States. It has affected not only price but production, imports, foreign policies, and other aspects of the economy that have in some instances limited it to grow to its full potential. The steel tariffs at one point drove the majority of steel production out of the United States and turned the U.S. into a net importer of steel. These tariffs heavily impacted the economy and the society of the United States in many ways and this paper will hopefully try to instill some further knowledge of the steel industry with a general focus on the Bush steel tariffs. History of Trade Flows and Policies: United States trade policies have varied significantly through the different economic periods of time. Whether it was the industrial period or simply impactful historical events, the United States has never seemed to have a set trade policy with any nation. Since the United States is a major developed nation, there is a heavy reliance on the importing of raw materials and then turning those raw materials around and exporting them as finished goods. With the primary view on U.S. trade being broadcasted in this manner, trade policies have always been a major topic on the minds of the American consumer. The United States is one of the significant countries in the world when it comes to international trade. It has led the world in imports while continuously remaining one of the top 5|Page three exporters for the past decade. Since the United States is a major epicenter of trade in the world, it has the ability to leverage its trading activities and policies in ways that many other countries cannot. One example is that the United States is considered the world’s leading consumer; it also means that the country can be classified as the number one customer for companies and countries around the world. A lot of businesses and countries compete for a share of the United States market, and if they succeed those companies and or countries will ultimately be successful in the long run. With the demand for a share in the U.S market and the U.S. being a top export nation for nearly 60 trading countries, the United States is able to use that leverage to impose economic sanctions across the world. In the last decades, the steel industry has been plagued by various tariffs and quotas. Either they were voluntary restraint agreements, antidumping regulations, or other import restricting and relief measures such as the Reagan Trigger Price Mechanism. It seems the problem will never be solved with simple reactive trade restrictions because those retaliatory actions have been going on for decades and the United States is still considered the world’s net importer of steel products. Since the tariffs and quotas have been enacted for long run periods of time it has led to more investment into foreign steel mainly imported from China (see graph 1). The United States government was said to reduce its interference in global steel trade because import restrictions are not in the best interest of the economy or the people in the United States. With that being said, it led to President Reagan not only putting import quotas on foreign steel once during his term nut twice. Reagan contradicted his saying that “import restrictions are 6|Page not in the best interest of the economy and the steel market should be in accordance with free trade” and expanded the import quota on foreign steel to 18.5% in 1984 (ita.doc.gov). After Reagan enacted the quota it led to President George H.W. Bush to extend the quota in 1989 to last for two and a half more years, he called it the “Steel Trade Liberalization Program” (Liebman 2007). President Bush’s extension was taken on much the same manner as Reagan’s approach of that government intervention needs to be reduced in the global steel trading market. Much to the public and steel Union’s demise however, the quotas were still enacted and the U.S. government still maintains control of foreign steel imports. Current Trading Patterns and Partners: The global market for steel is dominated by a select few countries: China, The EU, United States, Japan, and Russia, with other smaller market players being comprised mainly of India, Germany, and South Korea. China comes in at number one, producing as of 2006, 420 million metric tons of raw steel, which accounted for 35 percent of the entire global market. 2006 was an important year for China as well in that it moved from being a net importer of steel to a net exporter that year, accompanied by a 20.3% increase in its raw steel production. Currently, China is approaching 50% of export volume in the world market. The United States is a net importer of steel, and China recently became a net exporter, which has sounded alarms for the domestic steel industry. However, the United States does not necessarily get all of its steel from the world’s largest producers; instead it opts to purchase large quantities from nearby trade partners, such as Canada. This means that global share of steel exports do not imply share of U.S. imports. The 7|Page following table from the census accounts shows total value in thousands of dollars of all steel imports by country, over the years of 2008-2009. Country Total Import Value 2008 Total Import Value 2009 Canada 6,851,533 3,404,249 Mexico 3,201,439 1,341,677 EU 7,561,314 4,193,534 Japan 2,128,107 1,579,405 China 5,964,470 1,991,617 South Korea 2,206,453 1,103,528 Russia 942,422 348,381 India 1,735,143 820,858 One key trend that can be taken from this pattern is the marked decline of imports from the year 2008 to 2009. In some cases, imports are almost halved. This began in 2007 with the onset of the recession, as imports and US domestic demand for steel plunged. In 2009, the real value of steel imports decreased from the previous years, one of only six times in the past fifty years (Griswold 2010). Current Patterns by Major Country: China: China is the subject of many trade sanctions and international disputes concerning the steel industry lately, with everything from tariffs to anti-dumping measures being proposed by 8|Page the US ITC. One such anti-dumping action, concerning steel oil well piping, is estimated to reduce imports to the US by 2.8 billion dollars in an effort to protect stateside producers (Diana 2010). With the previously mentioned rise in Chinese supply to the world market, there is concern that the US industry, which is currently failing to meet domestic demand, will be supplanted by foreign competition. This tension has caused the mass lobbying for restrictive trade measures to be enacted against China. Piping is the most crucially affected import, with pipe exports falling by almost 50% from 2008 to 2009. Although Chinese exports are increasing, so too is its demand, causing competition for international steel buyers and sellers, and increasing price levels. Canada: Canada has historically been one of the largest, if not the main supplier of US steel imports, and this trend continues in the present. Although the EU now supplies more steel total, Canada far outstrips any single country in import levels. NAFTA is partially responsible for a great deal of modern trade volume, as modern shipments of steel across US-Canadian borders are done so duty free. Integration of the markets has also proved beneficial, as domestic firms have partial ownership in Canadian firms, and vice versa, with many businesses having the same suppliers of raw material. (Iron ore, etc.) However, the US ITC has found in recent years that Canadian steel exports may be threatening domestic steel industry. No action has taken yet, but this could potentially be a source of tension, as Canadian steel exports to the US accounted for 95% of total steel exports approximately during the last decade (("Canada-U.S. Steel Trade in an Integrated Market"). 9|Page The EU: The EU is the world’s second largest producer of steel, taking the aggregate output of its member nations together, and in recent years realized a trade surplus in steel, as its imports fell faster than exports. It maintains relatively low trade barriers with other nations, preferring to apply quotas on non-WTO members rather than tariffs. However, it has been embattled with the US in trade battles for most of this decade. President Bush imposed tariffs on EU steel imports in 2002, which were later ruled to be against WTO rules, leading to counter-tariff measures to be threatened by the EU. The Bush tariffs were eventually dropped, but not before EU exports for a year ("Industrial Goods: Steel"). Currently, the EU seems to be allying itself with the US against China, as the EU has also applied tariffs against Chinese steel piping imports, and accused the nation of dumping policies in appeals to the WTO. This seems to be strengthening the US connection, and loss of European trade with China due to tariffs will likely aid the US (Time Magazine). Current Trade Policy: The United States current trade policy is characterized most sharply by their involvement in international trade agreements, dating back to the end of WWII, when the country was instrumental in creation of the Bretton Woods institutions, such as GATT. This pattern of involvement in regulating international trade policy continues today, as the US is a prominent and founding member of the World Trade Organization, which was created out of the Uruguay Round of GATT talks. Today, the US uses the WTO as a means of dispute settlement with other nations, and generally applies tariffs per its rules. According to WTO data, the United States maintains a tariff schedule as follows: 10 | P a g e Non-Agricultural Duty rates Duty Free 0%5% 5%10% 10%15% 15%25% 25%50% 50%100% % of total imports in 2008 per tariff rate 48.3 41.1 6.2 .8 3.0 .6 0 This reflects the degree of openness with which the US trades ("United States Trade Profile"). The US also currently has many trade disputes pending, especially with China, which as previously mentioned has been massively increasing trade volume. In terms of overall trade volume, China has increased its output by 13% in 2010 over the previous year, while the US has experienced an increase of only 1%. This rate of increasing imbalance in the world economy is responsible for a large deal of the tension and trade disputes concerning China ("Wall Street Journal"). Another organization that is important to current US policy is NAFTA. Due to the agreements set in place at NAFTA’s inception in 1994, the majority of trade between member nations is duty free, or was set to be gradually reduced under a planned time horizon of 15 years (2009 target date). This is partially responsible for the large amount of previously mentioned steel trade between Canada and the United States, along with geographic proximity (Topulous, Duke Law). NAFTA reached its peak for the steel market in 2004, when Mexican and US producers increased supply, holding Canada constant. Member nations expressed concern when China became a net steel exporter in 2006, anticipating legal battles due to unfair trade practices and worries of trade displacement (North American Steel Trade Committee). 11 | P a g e Aside from its membership in RTA’s and trade organizations, the US still holds trade restrictions in steel products against many foreign countries. The table below lists specific types of steel products imported, and the range of tariff rates applied to the exporting nations, as given by the US International Trade Commission. Types of Imported Products Duty Applied Piping 25% to 50% AV Slabs Free sometimes 8.04/kg Spec. Hot Rolled $.04/kg + 20% AV Cold Rolled $.04/kg + 20% AV Galvanized $.04/kg + 20% AV Bars and Rods 5.5% to 20% AV Policy Evaluation 1: Starting on December 19, 2001, the U.S International Trade Commission (ITC) provided a report to the president, then George Bush, on the investigation under section 202 of the Trade Act of 1974 (Investigations, determinations, and recommendations by Commission), concerning the import of certain steel products. The ITC “reached affirmative determinations” that the following steel based products are being imported into the United States “in such increased quantities as to be a substantial cause of serious injury, or threat of serious injury, to the domestic industries producing like or directly competitive articles. These products include: tin mill steel, flat steel products, hot and cold rolled finished bars, carbon and alloy fittings and flanges, tubular welded products, stainless steel bars, rods, wire, rebar, and slab steel (Bush 2002.) See Graph 2. 12 | P a g e We chose to use the large nation model to demonstrate the effects of the tariffs on the United States (see above). As shown above you have the U.S importing steel, 1.27 million tons, from China at a world price of $325/ton. Once Bush slapped on the tariff the price of steel went up to $340/ton and imports decreased by about half to .613 million tons. This can be explained because for a large nation, a tariff on an imported product may be partially shifted to the domestic consumer because of higher product price and partially absorbed by the foreign exporter because of a lower export price (Carbaugh 2009). The upward sloping supply line reflects that the foreign supply price is not a fixed constant. The price can fluctuate depending on 13 | P a g e the quantity purchased by the importing county, in the case the United States. Because of the tariffs imposed by the U.S, steel prices increased for American consumers. This led to a decrease to the quantity demanded from the United States. Finally on March 5th 2002, George Bush came through on his word and imposed 8% to 30 % tariffs on various types of imported steel in an intervention aimed to help the ailing U.S. industries. Briefly after a statement by Bush, issued by the white house stated “An integral part of our commitment to free trade is our commitment to enforcing trade laws to make sure that America's industries and workers compete on a level playing field.” In the past few year’s more than 30 American steel makers have declared bankruptcy. Bush states that he takes these actions to “give out domestic steel industry an opportunity to adjust to surges in foreign imports (Money 2002).” Although leveling the playing field for the steel companies was going to have a direct effect on the US consumers and on American steel using industries such as automobiles and earth moving equipment. Thought the tariffs would temporarily save around 6,000 jobs, the cost to steel-using firms and U.S. consumers of saving these jobs was between $800,000 and $1.1 million per job (Money 2002). Furthermore the steel tariffs put into place by Bush would cost the steel-using industries 13 jobs for every one steel-manufacturing job protected (Carbaugh 2009). However the Bush tariffs did provide some liberation to U.S steelmakers, from an import perspective, thus causing producers to merge and labor contracts were negotiated. Because of frequent lobbying trips to Washington, chief executors of these firms noticed that the tariffs drove up their costs and endangered more jobs in the manufacturing field then 14 | P a g e they saved in the steel industry. Because of this, threats of trade wars from Japan and Europe, and political reasons, Bush decided to lift he steep steel tariffs only after 20 months of being implemented (Carbaugh 2009). Bush stated that the time the tariffs were in place, it had given the U.S. industry a chance to strengthen and modernize and were no longer needed as a result of "changed economic circumstances” (Bush 2002). Recommendation: Based off of the data we collected and researched we recommend that the government should not intervene in the steel industry. It seemed that through all of the due diligence that was performed a main theme was that the steel industry should be managed in a free floating market. This would increase the competition of the steel industry and the incumbents that deal with steel products. With steel becoming more competitive in the world markets it would lead to cheaper prices and would most likely push the United States out of the steel production market entirely. Another theme that was found to be relevant is that government would inform the citizens of tariffs being removed or quotas being dissolved but in the end it would never happen. With Reagan and George H.W. Bush making statements that “government should not intervene in the steel industry” and “we must do all we can to avoid protectionism” (Bovard 2002), the future administration of the United States needs to stick to their sayings. With the steel industry being associated with a free floating market we think it would greatly benefit all in the steel industry. The biggest effect would be the price of steel would most likely drop and although the labor force will coincide with that drop, the labor could be made up in other industries. If steel were to be cheaper, it would lead to a rise in steel “using” industries such as autos and heavy machinery, and the lost steel jobs could be expanded and replaced in the 15 | P a g e more efficient steel “using” industries. Once again the steel industry should be associated in a free market economy and we think that the effects it will have on the world’s production of steel will be very beneficial. Graphs: Graph 1: -U.S. steel imports from China (1990-2005) (ita.doc.gov) 16 | P a g e Graph 2: 35 Affected Steel Products by Tariffs Percent Increased by Tariff 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 17 | P a g e Works Cited Bovard, James. "The Future of Freedom Foundation. "Protectionist Welfare for Steel (2002): n. pag. Web. 28 Nov 2010. <http://www.fff.org/freedom/fd0209d.asp>. Carbaugh, Robert. International Economics 12th Edition. South-Western 2009. Cenrdrowicz, Leo. "Steel Wars: Europe and the U.S. Accuse China of Dumping." Time Magazine Saturday, Apr. 25, 2009: n. pag. Web. 1 Dec 2010. <http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1893784,00.html>. Diana, Initials. (2010, January 7). The effects of trade sanctions on china's steel mills. Retrieved from <http://www.chinasourcingblog.org/2010/01/the-effects-of-trade-sanctions.html>. European Union. Industrial Goods: Steel. , 18 December 2009. Web. 1 Dec 2010. <http://ec.europa.eu/trade/creating-opportunities/economic-sectors/industrialgoods/steel/>. Government of Canada. Canada-U.S. Steel Trade in an Integrated Market. , November 2001. Web. 1 Dec 2010. <http://www.canadianembassy.org/trade/steel-en.asp>. George Bush, Initials. International Trade Commission , (2002). To facilitate positive adjustment to competition from im- (10553). Federal Register : Retrieved from: <http://dataweb.usitc.gov/scripts/STEEL_MONTHLY/FR_7529_March_2002.pdf.> Griswold, Initials. (2010, September 7). Are rising imports a boom or bane to the economy. Retrieved from <http://www.aiis.org/downloads/Newsletters/2010/AIIS_>. Lee, Hiro. "Tariff Rate Quotas on U.S. Steel Imports: The Implications on Global Trade and Relative Competitiveness of Industries. "International Centre for the Study of East Asian Development and Graduate School of Social System Studies n. pag. Web. 28 Nov 2010. <https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/resources/download /1529.pdf>. Liebman, Benjamin. "Steel safeguards and the welfare of U.S. steel firms and downstream consumers of steel: a shareholder wealth perspective." Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique 40.3 (2007):812-836. Web. 28 Nov 2010. <Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique>. Money. (2002, march 5). Retrieved from: <http://www.usatoday.com/money/general/2002/03/05/bush-steel.htm>. North American Steel Trade Committee, . "The “NAFTA Steel Industry Pulse”." NAFTA Pulse #3 (May 20, 2995): n. pag. Web. 1 Dec 2010. <www.steelnet.org/new/20050500.a.pdf>. 18 | P a g e "The U.S. Steel Import Crisis." International Trade Association, n.d. Web. 28 Nov 2010. <http://www.ita.doc.gov/media/ch2.pdf>. Topulos, Katherine. "NAFTA." Duke Law November 2009. n. pag. Goodson Law Library. Web. 1 Dec 2010. <http://www.law.duke.edu/lib/researchguides/nafta>. "WTO: World Trade Growth Slowed Sharply In 3Q." Wall Street Journal December 1, 2010: n. pag. Web. 1 Dec 2010. <http://online.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20101201-710039.html>. "World Trade Organization." United States Trade Profile. N.p., 2010. Web. 1 Dec 2010. <http://stat.wto.org/TariffProfile/WSDBTariffPFView.aspx?Language=E&Country=US> 19 | P a g e