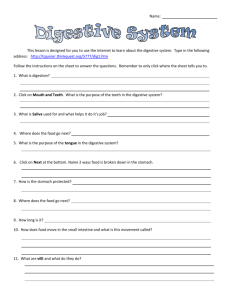

The Digestive System

advertisement

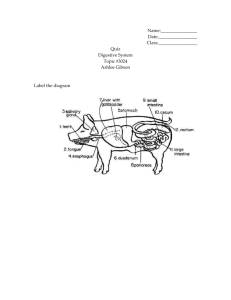

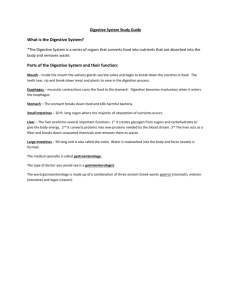

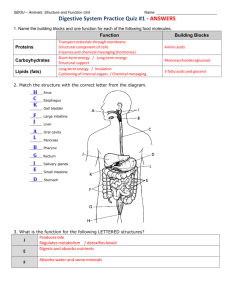

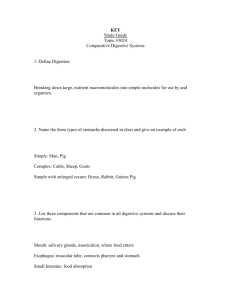

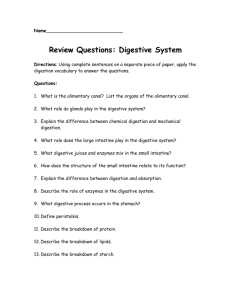

Lesson 5- The Digestive System Assignment: • Read Chapter 7 in the textbook. • Read and study the lesson discussion. • Complete the Lesson 5 worksheet Objectives: After you have completed this lesson, you will be able to: • Explain digestion in monogastrics, including exocrine secretions and function, digestive tract function, digestive tract absorption, and the role of the liver in digestion and metabolism. • Compare and contrast the specialization of dentition and digestive tracts found in the various domestic species. • Define symbiosis and its significance in the ruminant. • Discuss the clinical significance of the academic material in this chapter. • Identify common digestive system disorders. The Digestive System When discussing the digestive systems of animals, it is important to note that there are three different types of digestive systems veterinarians encounter—the monogastric, the ruminant, and the avian. All three digestive systems are based on the same premise and serve the same functions, designed with the purpose of taking in food to be broken down through chemical and physical means to be absorbed by the body for its nutritional requirements. In the textbook, there is a great discussion about the digestive system; be sure to make yourself familiar with the concepts presented. The Monogastric System Monogastric animals are those that have one stomach (a one-compartment stomach). Pigs, dogs, cats, rabbits, and humans are examples of animals that have one stomach compartment. Animals with one stomach must have more grains and fewer roughages in their diet. This is due to the "simpler" digestive tract involved in the monogastric animal. You will understand more about this concept after the discussion on ruminants. According to information obtained from The University of Florida IFAS Extension, Digestion is the breakdown of food occurring along the digestive tract. The digestive tract may be thought of as a long tube through which food passes. As food passes through the digestive tract, it is broken down into smaller and smaller units. These small units of food are absorbed as nutrients or pass out of the body as urine and feces. The digestive tract of [monogastric animals] has five main parts—the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestines, and large intestines. The mouth is where food enters the digestive tract and where mechanical breakdown of food begins. The teeth chew and grind food into smaller pieces. Saliva, produced by the mouth, acts to soften and moisten the small food particles. Saliva also contains an enzyme which starts the digestion of starch. The tongue helps by pushing the food toward the esophagus. The esophagus is a tube which carries the food from the mouth to the stomach. A series of muscle contractions push the food toward the stomach. Swallowing is the first of these contractions. At the end of the esophagus is the cardiac valve, which prevents food from passing from the stomach back into the esophagus. The stomach is the next part of the digestive tract. It is a reaction chamber where chemicals are added to the food. Certain cells along the stomach wall secrete hydrochloric acids and enzymes. These chemicals help break down food into small particles of carbohydrates, protein, and fats. Some particles are absorbed from the stomach into the bloodstream. Other particles which the stomach cannot absorb pass on to the small intestine through the pyloric valve. The small intestine is a complex tube which lies in a spiral, allowing it to fit in a small space. Its wall has many tiny finger-like projections known as villi, which increase the absorptive area of the intestine. The cells along the small intestine’s wall produce enzymes that aid in digestion and absorb digested foods. In the first section of the small intestine, the duodenum, secretions from the liver and pancreas are added. Secretions from the liver are stored in the gall bladder and pass into the intestine through the bile duct. These bile secretions aid in the digestion of fats. Digestive juices from the pancreas pass through the pancreatic duct into the small intestine. These secretions contain enzymes that are vital to the digestion of fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Most food nutrients are absorbed in the second and third parts of the small intestine, called the jejunum and the ileum. Undigested nutrients and secretions pass on to the large intestine through the ileocecal valve. A "blind gut," or cecum, is located at the beginning of the large intestine. In most animals, the cecum has little function. However, in animals such as the horse and rabbit, the cecum is very important in the digestion of fibrous feeds. The last major part of the digestive tract, the large intestine, is shorter, but larger in diameter than the small intestine. Its main function is the absorption of water. The large intestine is a reservoir for waste materials that make up the feces. Some digestion takes place in the large intestine. Mucous is added to the remaining food in the large intestine, which acts as a lubricant to make passage easier. Muscle contractions push food through the intestines. The terminal portion of the large intestine is called the rectum. The anus is an opening through which undigested food passes out of the body. Food that enters the mouth and is not digested or absorbed as it passes down the digestive tract is excreted through the anus as feces (Rowan et al). VIEW THIS ANIMATION WHICH ILLUSTRATES AND EXPLAINS THE STEPS OF THE MONOGASTRIC SYSTEM . The Ruminant System For the most part, the digestive system of ruminants is very similar to that of other mammals, but the stomach is considerably different from the monogastric. The function of the ruminant system overall is the same; it is just a different way to get to the end result. Cows, llamas, sheep, and deer are all examples of animals with the ruminant digestive system. Have you ever heard someone say that cows have "four stomachs?" If so, you should know that, in an anatomical sense, this is incorrect. According to Dr. Thomas Caceci, a professor from the Virginia—Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine, … There really is only one stomach, but it does have [four] divisions …. In monogastric animals, the stomach's functions are limited to temporary storage and preliminary [breakdown] of food into a liquid mass; little or no absorption of nutrients takes place. In ruminants, however, the stomach has an absorption function in addition to the usual functions of mastication (breakdown) and acidification. The evolutionary success of the ruminants as a group is based on the efficiency of their digestive system in extracting nutrition from low-quality food. This is why cows are able to be fed low-quality feedstuffs. Special microorganisms that thrive in the ruminant system are able to break down large amounts of lowquality roughage high in cellulose. Cellulose is basically the "fatty tissue" in plants that all other herbivores, except ruminants, cannot utilize. Yet, the fat released from cellulose in the ruminants’ system is a large part of their dietary budget (Caceci). The four divisions of the ruminant stomach are the rumen, the reticulum, the omasum, and the abomasum. The rumen is an enormous space filled with chewed and half-chewed materials the cow has ingested, swallowed, regurgitated, and swallowed again (often several times.) A combination of mechanical mastication and enzymatic action on the hard cellulose material of the cow's diet permits the breakdown of these otherwise indigestible materials. A [ruminant who is] "chewing her cud," is methodically grinding the food into smaller and smaller bits (Caceci). The reticulum is oftentimes referred to as "the honeycomb." Again, very little absorption takes place in this compartment. There is an additional amount of chemical breakdown that occurs here. The reticulum is also the compartment that traps any unwanted materials such as metal objects. Wire and nails are two very common metal objects that cows and other ruminants tend to eat, usually by accident. These indigestible, sharp objects can easily cause serious problems when they puncture the wall of the stomach. Dr. Caceci explains treatment for this problem: One way to deal with this is to have the cow swallow a magnet, which attracts and holds the metals and prevents them from migrating to a place where they can do damage as they slosh around in the vast caverns of the stomach. There is a brisk trade in recycling these magnets which are recovered at slaughter and reused. The nickname for injuries and illness caused by ingested material is "hardware disease." The food material then enters the omasum. This stomach has folds that resemble the pages of a book. It is in the omasum that water and other nutrients are absorbed and the ingesta (swallowed food) begins to turn into fecal matter. The abomasum is called the "true stomach" because it most resembles the functions of the stomach in the monogastric. Most of the physical and chemical breakdown is finished in this compartment before it is sent on to the small intestine (Caceci). The remainder of the digestive system of the ruminant—the small and large intestines, the cecum, and the anus—all function very similarly to these organs of the monogastric system. The Avian System To a lesser degree than the previous two, you will see the avian digestive system in the vet clinic. This system has a substantially different set-up than the other two systems, but the fundamental principle of this system is the same—to turn foodstuff into usable nutrients for the body while excreting fecal waste material. In the article "Avian Digestive System," author Sherri Carpenter notes that as the bird swallows food, it mixes with saliva so that it can slide easily down the esophagus. Remember, birds do not have teeth so there is no physical breakdown of food in the mouth. The food ends up in the crop at the end of the esophagus where it sits and softens before entering the stomach. Birds have a two-part stomach; one is glandular and one is muscular. The first is the glandular stomach, which is called the proventriculus. This is where gastric juices are secreted and are absorbed into the feed. These juices are composed of hydrochloric acid, enzymes, and mucous. It is the hydrochloric acid that works to activate the enzymes. It is here that the chemical digestion of food begins. The food then moves to the muscular stomach, the gizzard. The gizzard is extremely thick. If you have ever butchered chickens and cleaned gizzards, you know that they are full of feedstuff and rocks. Rocks are used to aid the gizzard in the mechanical breakdown of the food. You may notice that birds constantly peck at the ground; this is because they are swallowing rocks for the gizzard. Food may pass back and forth from the proventriculus to the gizzard to aid the breakdown of food. Next, the food enters the small intestine through a valve called the pylorus. The pylorus only allows a small amount of food to pass through at a time. The small intestine is lined with villi and microvilli. These villi continue to break down the food. The three sections of the small intestine are the same as described in the monogastric and ruminant system (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum). Carpenter continues, The liver and the pancreas secrete their fluids to the duodenum through a common duct. The pancreas produces enzymes that break down all categories of digestible foods. The enzymes will complete the digestion [process]. The liver's primary function is to produce bile, a watery solution that aids in more digestive processes. There are also certain cells in the liver that destroy any bacteria that have gotten through the walls of the digestive tract and into the blood. The liver also detoxifies drugs, degrades hormones, and makes many substances that are necessary for metabolism. One final function of the liver is to maintain the glucose (sugar) level in the blood (Carpenter). In addition, Carpenter explains that, The gallbladder is the storage house of the bile and is connected to the duodenum through the cystic duct. The bile is concentrated by the removal of water and is made available to the duodenum when fatty foods stimulate a hormone response to the gallbladder to send out the stored bile … . The large intestine (colon) is relatively shorter in birds compared to mammals. This helps with quicker elimination to prepare for flight. The large intestine's main function is to absorb water, dry out the indigestible foods, and eliminate waste products … . The large intestine also contains bacteria that collect the remaining nutrients. The large intestine joins the cloaca, which is where the feces meet with urine from the kidneys. Digestive Disorders When an animal's digestive system is running smoothly, all is well. However, just as in any other system of the body, when abnormalities arise, severe conditions can result. During the digestive process, various organs reduce food into nutrients that the animal's body can absorb and utilize to maintain health. There are several conditions of the digestive disorder than can occur in all species of animals. Two of the most common conditions are vomiting and diarrhea. According to an article obtained from Pets Health.com, "Food moves from the mouth to the stomach via the esophagus. Inflammation or obstruction of the food tube is referred to as megaesophagus." In this condition, there is a weakening and dilation of esophageal muscles that will cause the animal to regurgitate food before it even reaches the stomach. As the stomach churns food into a thick liquid (chyme), special glands secrete enzymes that break down proteins, hydrochloric acid that aids those enzymes, and mucus that protects the stomach from digesting itself. Vomiting is the most obvious sign of stomach inflammation. The article continues and indicates that "most of the digestion and nutrient absorption occurs in the small intestine, where more enzymes and mucus are added." Once the small intestine has begun digestion, the food mass continues to the large intestine where water continues to be absorbed. Finally, the large intestine pushes the now-digested food, in the form of feces, to the anus. Difficulties in digestion can often be diagnosed by a visual stool examination. For example, if an animal has "watery diarrhea with no blood or mucus, does not strain when defecating, and eliminates on a normal schedule, its small intestine is probably inflamed." Conversely, if the animal has "mucousy diarrhea tinged with fresh blood, strains when defecating, and has frequent urges to move its bowels, its large intestine is probably inflamed." There are many causes of digestive disorders with the most common being a change in the diet. Other causes include toxins, food allergies, infection, cancer, foreign bodies, metabolic diseases, organ failure, and parasites. These ailments usually affect the animal by stalling "the digestive processes, causing constipation while others rush food through the system too quickly, resulting in minimal nutrient and water absorption and a large volume of loose feces." If your animal experiences any digestive disorders, call your veterinarian to discuss the situation. Depending on the seriousness of the problem and the demeanor of your pet, a trip to your pet's doctor and an examination may be required. Here are some tips to help protect your animal from digestive disorders: • feed your animal a consistent diet appropriate for its age, weight, and overall health • make sure your animal's vaccinations are up to date • have your animal's fecal material checked regularly for parasites (twice per year) • limit your animal's access to foreign objects that can harm its digestive tract • prevent your animal from scavenging garbage cans or compost piles • keep toxic substances out of the animal's reach (PetsHealth.com). Summary Digestive tract differences among animal species present veterinarians with many challenges. Even though the process of digestion is the same for all animals, the systems vary considerably. Ruminants have multiple-compartment stomachs, dogs have monogastric stomachs, and horses have monogastric stomachs, accompanied with a specialized cecum to allow them to eat more feed. It is these unique features and the conditions associated with them that keep veterinarians on their toes. Sources Cited: Caceci, Dr. Thomas. "Urinary System." Veterinary Histology. 1998. 28 Dec. 2006 <http://education.vetmed.vt.edu/Curriculum/VM8054/Labs/Lab21/LAB21.HTM>. Carpenter, Sherri. "The Avian Digestive System." HolisticBird Newsletter. 3.1(Winter 2003). 28 Dec. 2006 <http://www.holisticbirds.com/pages/digestive0203.htm>. Columbia Animal Hospital. "Digestive Disturbances in Dogs." Pets Health.com. 28 Dec. 2006 <http://www.petshealth.com/dr_library/digestdistdogs.html>. Oracle Education Foundation. "The Respiratory System." ThinkQuest. 1996. 28 Dec. 2006. <http://library.thinkquest.org/2935/Natures_Best/Nat_Best_Low_Level/Respiratory_page.L.html>. Rowan, J.P. et. al. "The Digestive Tract of the Pig." University of Florida IFAS Extension. Dec. 1996. 28 Dec. 2006 <http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/AN012>.