APPLICATION HOLY WARS OR A NEW REFORMATION

advertisement

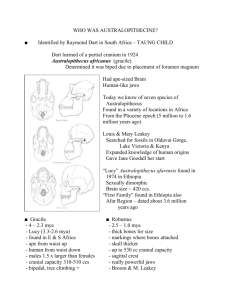

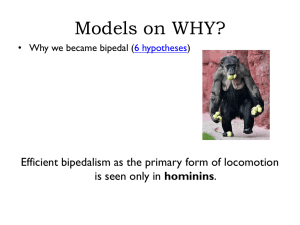

Understanding the origins of socio-technical humans and their organizations — Coevolution of technology, cognition, culture and organizations William P. Hall President Kororoit Institute Proponents and Supporters Assoc., Inc. - http://kororoit.org william-hall@bigpond.com http://www.orgs-evolution-knowledge.net Access my research papers supporting the work from Google Citations Application Holy Wars or a New Reformation a fugue on the theory of knowledge Hypertext book explores coevolution and revolutions in human cognition and cognitive technologies leading to the emergence of modern knowledge-based sociotechnical organizations as living entities Last episode explains how coevolution of cognition and technologies enabled forest-dwelling apes to become “human” and dominate the entire planet in something like 4 my. Key discoveries over the last 2-3 years allow construction of a complete evolutionary hypothesis – – 2 – Genomics Paleontology Paleoarchaeology – – – Comparative biology Comparative ethology Cognitive science Book theme: Revolutions in material technology cause grade shifts in the ecological nature of the human species M = millions, K = thousands, C = centuries, D = decades, Y = years, (A = ago) Accelerating change in our material technologies: – – – – – 3 > 2.5 mya - Tool Making: sticks and stone tools plus fire extend human reach, diet and digestion ~ 11 kya- Agricultural Revolution: Ropes and digging implements control and manage non–human organic metabolism ~ 3.5 ca - Industrial Revolution: extends/replaces human and animal muscle power with inorganic mechanical power ~ 5 da - Microelectronics Revolution: extends human cognitive capabilities with computers > 10 ya - Cyborg Revolution: convergence of human and machine cognition with smartphones (today) and neural prosthetics (tomorrow) Grade shifting revolutions in human technologies repeatedly reinvent the nature of human cognition Accelerating change in extending human cognition – – – – – – 4 – ~ 5 mya – Tacit transfer of tool-using/making knowledge begins to add cultural inheritance to genetic inheritance ~ 500 kya - Emergence of speech for the direct transfer of cultural knowledge between individuals ~ 11 kya – Invention of physical counters (11 K), writing and reading (5 K) to record and transmit knowledge external to human memory (technology to transfer culture) ~ 5.6 ca - printing and universal literacy transmit knowledge to the masses (cultural use of technology) ~ 32 ya - computing tools actively manage corporate data/ knowledge externally to the human brain (32 Y) and personal knowledge (World Wide Web - 18 Y) ~ 10 ya- smartphones merge human and technological cognition (human & technological convergence) ~ Now: Emergence of human-machine cyborgs (wearable and implanted technology becoming part of the human body) Some recent milestone publications constraining the development of an evolutionary hypothesis explaining how this happened Critical species of Homo Dmanisi Georgia (Lordkipanidze et al. e.g., 2013) – – – Modern sibling species: analysis of highly accurate genomes from modern sapiens and Denisovans (Meyer et al. 2012) & Neanderthals (Prüfer et al 2014) from Denisova Cave, Altai Mountains, Siberia show – – 6 Variation in H. georgicus shows H. erectus, ergaster, & probably also rudolfensis and habilis form one chronospecies persisting through time erectus longest lived Homo, spread widely through Africa and (via Dmanisi) Eurasia floresiensis (Hobbit) lived a few thousand years ago on Flores (Indonesia) probably derived from erectus (Kubo et al. 2013). Wood, B. 2012. Facing up to complexity. Nature 488, 162-– 163 - http://tinyurl.com/k53ofwy. Evolutionary divergence ~ 300 kya, Limited interbreeding with introgression Hybrid infertility sufficient for effective isolation Fossils (1.8 my) first hominins out of Africa – ancestor/early Homo erectus Lordkipanidze, D., et al. 2013. A complete skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the evolutionary biology of early Homo. Science 342, 326-331 http://tinyurl.com/kbnwxnn. (Oct. 2013) 1.8 mya ~550-730 cc cranial capacity, fully bipedal, scavanged or hunted large game with Oldowan grade butchering tools; first hominins out of Africa (Hertler et al. 2013) Individual had been toothless for years before death, implying strong social support network? 7 Lordkipanidze, D., et al. 2005. The earliest toothless hominin skull. Nature 434, 717-718. Latest genomics (5 my) establishes accurate genealogy, showing bifurcations and interspecific hybridization Prüfer, K., et al., Pääbo, S. 2014. The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains. Nature 505, 43–49 – http://tinyurl.com/lvg96n2. Red arrows show interspecific hybridization with introgression of genes and proportion of genome introgressed (Dec. 2013) 4500 kya Meyer, M., et al., Pääbo, S. 2014. A mitochondrial genome sequence of a hominin from Sima de los Huesos. Nature 505, 403–406 - http://tinyurl.com/lv6z8xo From 300-400 kya fossil Homo 8 Shows stepwise genealogical derivation based on sequence of single nucleotide mutations (Dec, 2013) Hominins exiting the East African homeland 9 Genomic analysis shows all living humans descended from people living in the E or S Africa some 70 kya. Eurasian mDNA six steps derived from oldest African Neanderthal/Denisovan ancestor (anticessor / heidelbergensis?) entered Eurasia before sapiens emigrants from Africa Eriksson A et al. PNAS 2012;109:16089-16094 Except for genes surviving from limited introgressive hybridization where they met Neanderthals & Denisovans, African emigrants to Eurasia replaced all pre-existing hominins including the wide-spread H. erectus that entered Eurasia by 1.8 mya. Behar 2008; Cruciani et al. 2011; Rasmussen et al. 2011; Oppenheimer 2012; Henn et al. 2012; Sankararaman et al. 2012; Pugach et al. 2012; Boivin et al. 2013; Mellars 2013; Fu et al. 2013; Rohling et al. 2013; Sankararaman et al. 2014; Vernot & Akey 2014; Thinking about hominid evolution Paleoclimatology over 7 my describes a framework of fluctuating ecological change driving hominin evolution Hominin evolution and environmental variability over the past 7 million years. Alternative responses to variability – – – 11 Genetic adaptation (change) Cultural change Cultural accumulation Potts, R. 2013. Hominin evolution in settings of strong environmental variability. Quaternary Science Reviews 73, 1-13 Genes & memes – genetic vs cultural adaptation Genes – – Determine individual anatomical, physiological and neurological capacities Mutation: physical change to one or more DNA nucleotides on a chromosome 12 Change is slow multi-generational process depending on natural selection Movement rather than increased versatility Meme = unit of culture (an idea or value or pattern of behavior or knowledge) that may be passed between individuals or from one generation to another by non-genetic means – Change often intra-generational depending on innovation, social relationships and processes – Transmission limited by genetic capacity to communicate detailed information – Essential information easily lost or corrupted over generations. – Rate and extent of cultural accumulation depend on genetic capacity, group size, (culturally transmitted) cultural practices Adaptation = application of genetic or cultural knowledge to solve problems of life Natural selection on genes works at the level of individual genetic variation depending on successes of carriers of particular genes in the population Selection on cultural knowledge works at the level of culturally variant groups, depending on successes of the different groups. – – 13 A group whose shared cultural knowledge allows it to solve problems other groups can’t solve grows at the expense of those other groups Successful items of cultural knowledge may be carried by individuals between groups to speed the evolutionary arms race Rate of cultural evolution depends on individuals’ genetically determined capacities to understand, remember, and transmit cultural knowledge Niche shifts (left) vs niche expansions (right). Vertical axis represents survival probability of particular phenotypes. Niche shift – – Niche expansion – 14 Mutation is blind Natural selection tracks current requirements, generally with continuing specialization – Retain original adaptation together with adding new capabilities, i.e., accumulation or (very rare) cases of gene duplication and functional divergence New mutation crosses adaptive threshold opening new adaptive landscape (i.e., grade shift) Thinking about making & using tools ― Cognitively controlled processes to kill prey with a stone-tipped spear Understanding cognitive demands of technologies Thinking a stone-tipped spear – – – 15 Long sequence of steps over time to make a spear used to bring down prey (chains of operation/cognigram) making a bow and arrow set is at least 3x more difficult each arrow indicates ordered application of specific knowledge (“Chain of operations” Lombard 2012; Lombard & Haidle 2012) Evolutionary hypothesis ― How tool-using savanna apes came to dominate Planet Earth Socially foraging, tool-using forest apes in East African Rift Valley 5 mya Adaptive plateaus achieved in the Pliocene as our ancestors became more bipedal and better adapted to open and arid environments (White et al. 2009) (click pictures below to view videos) 17 Chimps using probes to collect ants. Probe is inserted almost to full length into earth. Child watching mother crack otherwise inedible palm nuts using stone hammer & anvil. Climatic deterioration in E African Rift Valley left forest apes stranded on grassy woodlands and savanna ~5 mya Chimpanzee last common ancestor (CLCA) – – Fission-fusion social structure, some transfer of cultural knowledge High selfishness, limited cooperation in defense and hunting Savanna ape faced survival problems – – Edible plant resources more widely scattered and harder to find New food resources needed – New dangers Big cats Hyenas Wild dogs Bears Selection pressures – – 18 Roots, tubers, nuts Meats (Tattersall 2012 – “Masters of the Planet”) Increasing need to retain and transfer cultural knowledge Pressure to increase brain capacity: increased fine motor skills, social learning, more cohesive and cooperative group dynamics Cooperative defense and scavenging of carnivore kills cached in trees gave early hominins increased access to meat on the savanna Savanna offers limited resource of edible plant foods but a rich supply of grass-eating herbivore meat Chimpanzee social defence against leopards is uncoordinated mobbing with clubs as per video (click to view) - Simple requisites for grade shift to aggressive scavenging on the ground – – 19 Might deter leopard from returning to tree cache Not a pride of lions or mob of hyenas on ground Coordinated & cooperative defense and offense using effective deterrence Oldowan butchering tools for cutting skin & ligaments Hominins using haak en steek branches as tools (Guthrie 2007): a. for driving big cats away from their prey. b. for hunting - given the simple conversion of a thorn branch into a "megathorn" lance. Impacts of environmental change and variability in E African Rift (Olduvai, etc.) between 3.0 and 1.5 mya Long periods (∼130–330 ky) of extreme moist-arid variability between 3.0 and 1.5 mya. Possible modes of adaptation – – – Genetic adaptation – – – – – 20 Slow & ponderous (intergenerational) One thing or the other not both Cultural adaptation – Fail to track (= extinction) Adaptive change to track (shift niche) Increase versatility (expand niche) Potts, R. 2013. Environmental and behavioral evidence pertaining to the evolution of early Homo. Current Anthropology 53(S6), S229-S317 - http://tinyurl.com/mcnje6c Fast (intragenerational) Cultural knowledge pertains to group only (→ group selection) Group knowledge easily lost (depending on genetically determined capacities, group size, structure, and dynamics) Culturally transmitted tool using/making knowledge was grade-shifting Savanna ape inherited limited capacity to transmit cultural knowledge and existing culture of simple tool-making and use from CLCA Comparative anatomy and biology: climatic pulse rapidly changing ecology selects for increasing brain capacity (Dmanisi) Shultz, S., Maslin, M. 2013. Early human speciation, brain expansion and dispersal influenced by African climate pulses. PLoS ONE 8(10): e76750. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076750 - http://tinyurl.com/m38zfke Brain capacities correlate with cognitive capacities (many works over many years). Major climatic pulse (expansion/contraction E African Rift lakes) causes rapid ecological variation ~1.8 mya – – – 21 – Proliferation hominin species Initial colonization of Eurasia (Dmanisi) Rapid increase in brain capacity in H. erectus (broadly defined) Acheulean hand axes begin to appear around 1.7 mya. With thorn branches, spears and stone butchering tools, hominins became top carnivores on the savanna Oldowan tools made & used from 2.6 to 1.7 mya – – – – More sophisticated Acheulean hand choppers & other tools made & used from 1.7 mya to 0.1 mya facilitated butchering but required greater knowledge & dexterity to make Note exceedingly slow rate of technological change – 22 Hominin teeth can’t tear skin and flesh of large prey Anvils & hammer stones used to access marrow from scavenged carcasses Kanzi the bonobo learned to break stones & use flakes as cutting tools Early hominin culture assimilates knowledge that broken hammer stones can be used to cut skin & ligaments for butchering large prey before lost to competing carnivores and scavengers Suggests neural/social/linguistic capacity to accumulate knowledge of complex technologies was stringently limited for most of hominin history By 3 to 2 mya hominin competition and dominance of other carnivores begins to reduce overall carnivore diversity in E. Africa 23 Large carnivores included lions, Werdelin & Lewis 2013. leopards, three sabertooth cats, large bear, bear-sized wolverine, several large hyenids, wild dogs, etc. 3 mya aggressive scavenging of kills reducing food supply for some carnivores causing local extinctions. 2 mya active hunting of large mammal prey using spears + Oldowan butchering tools further reduces carnivore resources. 1.8 mya hominins in Olduvai Gorge were top carnivores selectively hunting prime quality bovid prey (Bunn & Pickering 2010; Bunn & Gurtov 2013). By 1.8 mya carnivorous hominins extended to Dmanisi, Georgia (Hemmer et al. 2011; Carrion et al. 2011), and from there quickly spread across Asia and into Europe (as H. erectus) 2 – 1.5 mya selective environment for hominin carnivores affecting genetic & cultural changes Genetic enhancements to meet increasing cognitive needs – – – – Capacity for geographical (mental map) and natural history knowledge Understand time & process to plan & coordinate hunting Better neuromuscular control and knowledge of resources & planning for tool making & use Increased capacity for teaching & learning Cultural accumulation of knowledge begins to replace genetic change as most important adaptive mechanism – Knowledge accumulation still limited – 24 Facilitate master-apprentice and other social relationships Share and direct attention to critical aspects of process & technique Use gesture, mime and acting-out (dance) Capacity to remember Slow genetic evolution of more memory capacity Technological innovations may be lost & reinvented several times & may take hundreds of thousands of years to be consolidated Fire users, keepers, & makers Opportunistic users > 3 mya ? – – Savanna burns naturally every 2-5 years Knowing that just burnt savanna is a good source of high cuisine Fire keepers > 1 mya (Rolland 2004; Twomey 2011) – – – Keepers much better off (cooking, warmth, deter predators) Loss of fire potentially catastrophic to group Maintaining fire requires social coordination Know how to feed and keep a fire (process knowledge) Know how to move fire to a new place before fuel resource used up (anticipation, planning, techniques) – Keeping the fire is a driver to increase cognitive capacity – Knowing how to start a fire without a natural source Fire makers ~ 0.5 – 0.4 mya 25 roast meat much more digestible than raw Roasting makes inedible/indigestible nuts, roots & tubers edible Striking a spark (what rocks, what tinder?) Using a fire stick to create friction embers Cognitive skills needed to accumulate knowledge for niche expansion (Vaesen 2012; Sterelny 2011, 2012a, b) 26 Hand-eye coordination - fine motor control needs more neurons Causal reasoning - time-binding; understand goals, actions, and consequences Function representation - associate particular tools with particular jobs Natural history intelligence - conscious attention to understanding the behaviors of predators, prey, fire, other changing aspects of environment Executive control – anticipating, deciding & planning; not just reacting Social intelligence - extended childhood, social learning (imitation not emulation), understanding of intentions of others (mirror neurons?), focused teaching & learning, apprenticeship Intragroup coordination Intergroup collaboration Language Genetic & physiological enhancements facilitating the emergence of language Triadic niche construction: neural/cognitive/ecological (Iriki & Taoka 2012) Brocas’ Area – – – 27 Expanded area of brain involved in speech and fine motor control Identifiable in hominin endocasts – H. habilis like modern humans compared to apes. Mirror System Hypothesis (MSH) proposes primitive action-matching system evolved to support imitation, pantomime, manual ‘protosign’ and ultimately vocal language FOXP2 and other speech related genetic Red oval = Broca’s Area changes affected Broca’s area in our common Stout, D., Chaminade, T. 2012. Stone tools, and the brain in human evolution. ancestors with Neanderthals and Denisovans language Philosophical Transactions Royal Society B 367, Food processing technologies make food more 75-87 - http://tinyurl.com/kpotjro. digestible enabling natural selection to divert metabolic resources from the digestive system to development of larger brains Larger brains support increased cognitive capacity: memory, mental maps, greater social complexity, better neuromuscular coordination Language and the emergence of hominin groups as higher order autopoietic systems Language - phenomenon of groups not individuals (one hand clapping) Drivers for the evolution of a faculty of language – – Common language, cultural norms & xenophobia determine group boundaries Cultural knowledge propagated among individuals between generations by language determines group success on the adaptive landscape An entity is autopoietic if it exhibits all the criteria (Varela et al. 1974) – – – – – – 28 Coordinates individuals’ involvement in group activities and society Transmits essential cultural knowledge (heritage) Bounded (groups separated socially by cultural differences and breeding systems) Complex (groups formed by multiple individuals playing different roles in group) Mechanistic (interactions of group individuals determine group functions & activities) Self-referential (group identity determined by culturally transmitted knowledge) Self-producing (group retains its continuity beyond the lifetimes of single individuals through individual reproduction and recruitment combined with indoctrination in and transmission of accumulated cultural knowledge from one generation to the next) Autonomous (group manages its own survival and continuity through knowledge-based interactions of its individual members) Autopoietic entities represent units of selection Pre-linguistic groups probably qualified as autopoietic – but group identity and adaptive variation greatly strengthened by language-assisted cultural accumulation What enabled increasing tool complexity? Development of increasingly complex stone tools (Stout 2011) correlates with larger brain capacity and language development. Even with language, knowledge is limited by what can be learned, remembered, and passed on by single individuals. By < 500 kya, pace of change in the capacity to deal with multiple complexities is too fast for genetic adaptation < 50 kya increasing rate of change suggests major innovation to support accumulation of much larger volumes of knowledge. Oldowan Acheulian Introduction & exponential growth of new technologies 29 Indicators for the emergence of modern cognition in Neanderthals & H. sapiens Krubitzer, L., Stolzenberg, D.S. 2014. The evolutionary masquerade: genetic and epigenetic contributions to the neocortex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 24, 157-165. Dediu, D., Levinson, S.C. 2013. On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neandertal linguistic capacities and its consequences. Frontiers in Language Science DOI=10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00397/ Johansson, S. 2013. The talking neanderthals: what do fossils, genetics, and archeology say? Biolinguistics 7, 35-74. 30 “All modern human populations have language, and there is no difference in language capacity between living human populations. Parsimony implies that the most recent common ancestor of all modern humans had language, and had all the biological prerequisites for language” (Johansson 2013). The common distribution of language proxies across human and neanderthals in genomic, paleoanthropological, and paleoarcheological contexts show that human, Denisovan and Neanderthal common ancestor had a capacity for modern language, speech and culture (Dediu & Levinson 2013, etc.) Schöningen & Bilzingsleben Modified from Krubitzer & Stolzenberg (2014) Two extraordinary snapshots imply that linguistic capabilities already existed 400 kya in LCA Neanderthal / H. sapiens Schöningen II (single-use hunting camp 380 kya – Thieme 2005) – – – – Bilzingsleben (base camp 370 kya - Mania & Mainia 2005) – – – – – Captured, butchered and processed at least 20 horses Tools made elsewhere include 9 wood lances left (ritually?) with herd remains 4 hearths, associated tools & evidence for spit-roasting, smoking and drying Earliest evidence for compound tools 3 x 3-4 m dia. huts with hearths all oriented against wind Prey included fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, elephants, rhinoceros, horses, bison, deer, pigs, lions, bears, wolves, hyenas, foxes, badgers, and martens Spit roasting & smoking for preservation Evidence for making & use of wide variety of stone and bone tools Paved area with artifacts suggestive of ritual activities. Implications – – – – Long-range planning (harvesting and preserving; anticipating the need) Planning and coordinating cooperative hunting of large, dangerous animals Wide range of natural history, tool-making and food-processing knowledge Ritual activities/thinking Diversity 31 and complexity of cultural knowledge for inferred activities beyond the capacity to communicate without language. The Middle Stone Age (Africa) / Middle Paleolithic (Europe) was a post Acheulian technological plateau (~ 300 → ~ 50 kya) Primary references: Current Anthropology, Vol. 54, No. S8, Wenner-Gren Symposium: Alternative Pathways to Complexity: Evolutionary Trajectories in the Middle Paleolithic and Middle Stone Age (December 2013 – free to the Web) Acheulian tools continued to be used by other hominins (e.g., H. erectus) Technology variable through MSA / MP but no clear temporal trends – – Despite major ecological shifts between glacial and inter-glacial there is no evidence for permanent settlements or cultural shifts from nomadic hunting and gathering. – – 32 Sporadic development and loss of complex technologies Operational chains of limited length Little technological difference between Neanderthal/Denisovan/archaic H. sapiens in Europe, anatomically modern sapiens in South Africa, and AM sapiens in the Levant (eastern Med.) early colonization ~ 100 kya, and permanent colonization and spread to Eurasia ~ 70 kya Populations limited in size to small bands, with evidence that Neanderthals & Denisovans passed through more severe genetic bottlenecks than sapiens Even with language, the capacity for cultural memory was limited Slowly increasing pace of hominin technological innovation in the East African homeland 33 Even given the existence of a faculty of language, the pace of technological innovation was very slow before 100 kya. Use of fire in making fine blades and points, or use of ochre and beads may have been developed & lost several times before being fixed in culture Even where ideas can be expressed in words, an individual’s ability to remember detail is limited. Where population is divided into small groups any knowledge not securely acquired by the next generation is lost McBrearty & Brooks 2000 Something changed ~ 70-50 kya that enabled H. sapiens to increase its cultural capacity to store & transmit knowledge Mnemonics – increasing capacity for accumulating knowledge in primary oral culture differs from typographically based culture – – – Master technique: the method of loci (see next slide) – – – 34 Ong, W.J. 1982. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Routledge, London [eBook free download from http://tinyurl.com/ledoljk] Kelly, L. 2012. When Knowledge Was Power. PhD Thesis, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Latrobe University, Bundoora, Vic., Australia [embargoed until Cambridge University Press book is published - see http://www.lynnekelly.com.au/Lynne_Kelly/Research.html] Techniques - think memorably: express knowledge in rhythm and rhyme with common formulas and phrases, link breathing and gesture, act out, associate with song and dance, organize by intrinsic logic, etc. – Primary sources for understanding mental techniques used in primary oral cultures to accurately memorize and recall large and complex bodies of information: May increase individual memory capacity by 10 to 100-fold or more Use at group level to preserve and transmit cultural knowledge Cultural capacity depends on group size – larger groups allow formation of subgroups (i.e., “guilds”) to manage specialized bodies of knowledge Method of Loci builds on the natural rhythms and progression of life Memorable events happen in time and space (specific locus in 3D space) – – Songlines: – – hunter gatherers learned to consciously index geographic, resource & natural history knowledge against tracks in the existing landscape where it is relevant. Other knowledge may be indexed against loci on other shared lines (e.g., stars in the night sky) or with stories associated with landscape features, etc Method of loci uses an ordered sequence of memorable loci as indexing points along existing or imagined space-time lines – – – 35 Innate way to organize memory probably common to all “intelligent” animals Focus on the space-time locus to retrieve memories of circumstances and events that happened at that locus – – Associates memorably expressed snippets of knowledge with particular loci in the line Other mnemonic techniques make snippets memorable (e.g., imagery, rhythm, rhyme, oration, song, dance) Group rehearsal and repetition strengthens memory traces Group sharing adds redundancy and corrects errors in individual memory In larger populations subgroups can maintain specialized knowledge Becoming settled – surmounting the knowledge capacity of nomadic life in the post-glacial era Nomads limited to technology they can carry or fabricate on demand Accumulating technological knowledge enables more effective use of smaller geographic areas – larger populations accumulate more knowledge Becomes practical to establish core living areas with permanent goods & structures (e.g., specialized tools, houses, and structures for cultural activities and processing and storage of food and other property) Reduced contact with tracks in the broad landscape combined with need to manage more and more specialized knowledge of technology drives development of new and archeologically significant mnemonic systems Solution: When songlines no longer suffice, build compact monumental landscapes that can be traversed sequentially (Kelly 2012 - e.g., Stonehenge, Poverty Point, Chaco Canyon Kivas, etc.) – – 36 Early site: Göbekli Tepe ~ 11 kya southern Turkey 3 ky before the agricultural revolution Many other sites from primary oral cultures moving from nomadic hunting and gathering to settled life have similar monumental structures Mnemonics, settlement, the agricultural revolution and increasing cultural complexity Current Anthropology 52(S4), Wenner-Gren Symposium: “The Origins of Agriculture: New Data, New Ideas” (October 2011) reviews in detail the archeological record of cultural & demographic transitions from nomadic hunting & gathering to formation of agricultural towns With settlement, nomadic groups become territorial villages – Positive feedback drives ever-increasing growth rate of cultural knowledge accumulation for ever-increasing ecological hegemony over environmental resources – – – – 37 The autopoietic entity becomes a socio-technical construct comprised of people, their linguistically mediated communication networks, their knowledge, their technologies and their built environment Accumulating cultural knowledge enables more efficient/effective control of local resources Surplus resources enables population growth in turn providing more capacity for cultural memory Development of ever more sophisticated mnemonic devices Population growth enables more specialization of crafts, trades and guilds able to accumulate still more varied and detailed knowledge of the world Ecological grade shifts result in demographic transitions increasing socio-cultural/economic complexity Mobile hunter-gatherers (~15 – 20 adults in group – say 2-4 families) – – Part-time tool-makers & apprentices (specific resource and processes knowledge) Organized hunting parties – – – Gatherers use specialized geographic & natural history knowledge to find resources Temporary shelter construction, child-care, fire tending, food processing Extended networks for additional mating opportunities, knowledge exchange & barter Settled foragers (~ 40 adults in community – say 8 families) – – – – – – Specialized tools that can be kept on hand, perhaps leading to full-time specialization Wide ranging hunting parties transport butchered products back to home-base Locally intensive gathering and harvesting with processing and storage Construction & maintenance of permanent shelters & specialized structures Need to protect valuable “capital” (community / personal ”property”) “Tribal” networks & mnemonic systems for preserving & exchanging knowledge 38 Leader/organizers + possibly specialized team members Geographic & natural history knowledge target prey and dangers Skinning, butchering, processing Production of specialized goods and surplus resources encourages formal barter economy Social norms and knowledge specialties common to interrelated communities (“tribe”) Development of specialized “cultic” sites on neutral territory for rehearsal, standardization, and sharing of various bodies of knowledge The Agricultural Revolution extending human control over animal and plant metabolism Major techno-ecological transitions – – – Demographic revolution – egalitarian communities become hierarchically organized tribal regions and towns (encompassing dozens to hundreds of families) – – – Hunting → herding & corralling → husbandry, dairying, cheese-making, tanning, animal power & transport Harvesting, storage, milling, baking & brewing → planting → tilling & irrigating → hydraulic engineering Stone & mud construction → brick making & firing → ceramics, pottery & metallurgy → structural engineering Population growth and technological innovation leads to proliferating specialization & restriction of life roles: farmers, pastoralists, despots, leaders, warriors, administrators, traders, priests & healers, educators, masons, artisans (e.g., tool-makers, potters, tanners, bakers, candlestick-makers, smiths, armorers), etc. Specializations dependent on knowledge passed down via family specialization, confraternities, and guilds Management of surpluses, specialized production, and trading leads to development of formal economies and despotic/priestly states Revolutionary emergence of new mnemonic and knowledge management technologies to release cognitive demands for memorization for thinking and doing – – – Indexing living memory vs representing and preserving knowledge with objective symbols Reduction of the monumental landscape onto distinctive paths and loci sculpted/fabricated into hand-held objects Representing reality with symbolic tokens: 39 Counting and recording, the clerical accountant, taxing and contracting Logographic writing (cuneiform), scribes Phonetic alphabets Tablets, scrolls, libraries, & offices Increasing socio-economic complexity, economic speciation, and emergence of knowledge-based autopoietic entities at intermediate levels – Religious orders, trades, guilds, factories, chartered companies, societies The Industrial Revolution, the replacement of human/animal motive power, and the externalization of technological memory (560 ya) The rise of printing for the general recording, replication and transmission of knowledge – – – Technologies: papermaking, type founding & setting, printing, post-press, distributing, indexing, book making, curating, etc. Scholarly access to large volumes of general, historical, and specialist knowledge encouraging the deliberate accumulation of knowledge Renaissance, Reformation, & (~400 ya) Scientific Revolution Increasing literacy and access to technical knowledge fuels innovation (~ 300 ya) animal and human motive power replaced with inorganic sources – – – 40 – Publication & peer review Scientific societies Libraries & universities Mass production of many things, including books General literacy, social upheaval, dislocation and gradually rising affluence Ecological hegemony over land and sea Exponentially accumulating knowledge Emergence of knowledge-based economic organizations as autopoietic The Microelectronics Revolution and the increasing externalization and convergence of individual and social cognition ~ 150 ya mechanical and electro/mechanical technologies for corporate/scientific number crunching & data processing ~ 50 ya birth of electronic digital processing – – invention of transistorized logic circuits ~ 43 ya invention of integrated circuit microprocessors and automatic fabrication (Intel 4004 1971) ~ 35 ya automated processing, storage, distribution and retrieval of personal and corporate knowledge. (Wordstar 1979) ~ 22 ya networking knowledge with the World Wide Web (Tim Berners-Lee 1992) Universal access to the world knowledge base – – – ~ 20 ya Mosaic Netscape Navigator 1994 ~ 16 ya free open-source browsers Mozilla Firefox 1998 Indexing knowledge for retrieval 41 Moore’s Law & the still continuing hyperexponential growth of processing power Extending and replacing more and more human cognition ~ 14 ya one billion web pages indexed, more than two billion by end of 2000 Last decade provides instant web search, access & retrieval of virtually the entire scientific & technical literature via Google Scholar/research library subscriptions Majority of all English language book titles scanned, indexed, and available (if out of copyright), with smaller fractions non-English books processed. Networking brains directly – towards a singularity or global mind? Interconnecting minds and cognitive processes via the cloud “social computing” and convergent technology Technological convergence – mobile phone to a cognitive prosthesis – – – – – – – – – Email: ARPANET (1971), TCP/IP (1982), SMS text (2002), Gmail (2005) Internet telephony: Voice over IP (1994), Skype (2003) Media: iTunes (2000), Amazon Kindle (2007), Google Play (2008) Still and video imaging: Picassa/iPhoto (2002); Flikr photo/video (2004); YouTube (2005); Panoramio (geolocated photos converging with Google Earth/Google Maps – 2005) Cloud storage: Napster (1999), BitTorrent (2001), Amazon S3 (2006), DropBox (2008) Business/Office tools: Google Docs/Drive (2007) Geospatial: Google Earth/Maps 2005 Social: chat rooms (1980); Groups/Listservers (1992), LinkedIn (2003), Facebook (2004), Twitter (2006) Knowledge construction/sharing/broadcasting: Wikis (1994), Wikipedia (2002), Blogs/Wordpress (2003) Human-computer interfacing – – – Head-mounted displays (1960’s) Google Project Glass (2012) Implanted/embodied human-machine interfaces 42 Cochlear implants/Bionic Ears Retinal implants/Bionic Eyes Direct brain stimulation Brain simulation and emulation