Neuropathic pain

advertisement

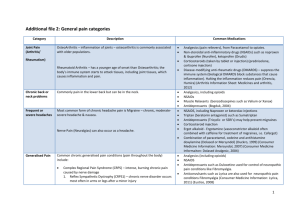

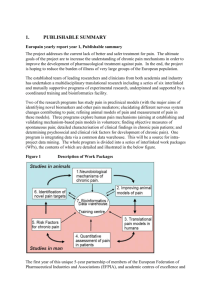

BeCOn OWN Educational Program Modules Module 1 An introduction to cancer pain Date of preparation: June 2015 HQ/EFF/15/0024 Contents Pathophysiology of pain Types of cancer pain Incidence, assessment and burden of cancer pain Challenges in management of cancer pain Pathophysiology of pain Pain can be described in two major categories Acute pain Chronic pain A protective mechanism that provides survival benefit or contributes to the healing process Chronic pain that involves pathology of neural structures Chronic pain has been defined as a pain that lasts beyond the duration of insult to the body or beyond the duration of the healing process Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP; 2012. National Pharmaceutical Council. http://www.npcnow.org/publication/pain-current-understanding-assessment-management-andtreatments. Accessed 8 Jun 2015. Classification of pain Nociceptive pain Noxious stimulus to a tissue (somatic) or to a visceral organ (visceral) Mixed pain Pain that is a combination of nociceptive and neuropathic pain Neuropathic pain Arises from abnormal neural function as a result of direct damage or indirect insult to a neural tissue involved in pain processing In cancer, pain can be the presenting symptom of cancer in an otherwise healthy patient or emerge as disease progresses http://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673. Accessed 15 Jun 2015. Classification of pain Nociceptive pain results from an acute or persistent injury to visceral or somatic tissues – Somatic nociceptive pain: site specific, described by patients as “aching”, “stabbing” or “throbbing” , “tender”, “squeezing” and involves injury to bones, joints, skin, mucosa or muscles – Visceral nociceptive pain results from injury to organs or viscera, is poorly localised and/or referred and may be characterised as “cramping” or “gnawing” if it involves a hollow viscus (e.g. bowel obstruction), or as “aching”, “stabbing” or “sharp” (similar to somatic nociceptive pain) if it involves other visceral structures such as the myocardium Neuropathic pain suggests injury to the peripheral or central nervous system. Neuropathic pain may be associated with referred pain along nerve distribution (pain is perceived in a location that is not the source of the pain), and all other descriptors of pain. It is described as “shooting”, “sharp”, “stabbing”, “tingling”, “ringing”, “numbness”. It is caused by radiculopathy, peripheral neuropathy, phantom limb, spinal cord compression Ripamonti CI, Bossi P. Cancer pain. Rehabilitation issues during cancer treatment and follow-up. ESMO Handbook, 2014. Pain terms Allodynia: Pain due to a stimulus that does not normally provoke pain Causalgia: a syndrome of sustained burning pain, allodynia, and hyperpathia after a traumatic nerve lesion, often combined with vasomotor and sudomotor dysfunction and later trophic changes Central neuropathic pain: Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central somatosensory nervous system Dysesthesia: an unpleasant abnormal sensation, whether spontaneous or evoked Hyperalgesia: increased pain from a stimulus that normally provokes pain Hyperpathia: painful syndrome characterised by an abnormally painful reaction to a stimulus, especially a repetitive stimulus, as well as an increased threshold. Paraesthesia: an abnormal sensation, whether spontaneous or evoked http://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy. Accessed 15 Jun 2015. Nociceptive vs. neuropathic pain Nociceptive pain Caused by activity in neural pathways in response to potentially tissue-damaging stimuli Postoperative pain Mixed Type Caused by a combination of both primary injury and secondary effects Arthritis Mechanical low back pain Sickle cell crisis Sport/exercise injuries Neuropathic pain Initiated or caused by primary lesion or dysfunction in the nervous system Complex regional pain syndrome Postherpetic neuralgia Neuropathic low back pain Distal polyneuropathy (eg, diabetic, HIV) Trigeminal neuralgia Central poststroke pain Cancer pain may be due to a variety of causes Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP; 2012. National Pharmaceutical Council. http://www.npcnow.org/publication/pain-current-understanding-assessment-management-andtreatments. Accessed 8 Jun 2015. Physiology of pain perception Brain Transduction Injury Transmission Modulation Perception Interpretation Behaviour Descending pathway Peripheral nerve Dorsal root ganglion Ascending pathways C-fiber A-beta fiber A-delta fiber Dorsal horn Spinal cord Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP; 2012. National Pharmaceutical Council. http://www.npcnow.org/publication/pain-current-understanding-assessment-management-andtreatments. Accessed 8 Jun 2015. Nociceptive pain: transmission Central perception Cortex Thalamus Relay and Descending Modulation Brainstem Transmission Spinal cord Conduction Peripheral stimulus Signal transduction Normal pain signalling in the body is transmitted to the spinal cord dorsal horn through nociceptors. Fornasari D. Clin Drug Investig. 2012;32 Suppl 1:45-52. Neuropathic pain: peripheral sensitisation Mechanical Chemical Thermal P ↑Na+/Ca2+ influx ↑Generator potential (membrane depolarisation) ↑Reach voltage-gated sodium channel threshold ↑Action potential PKC activation Sensitising agents PKA activation Tyr TrkA P Na+ Peripheral sensitisation takes place in inflammatory pain, in some forms of neuropathic pain and in ongoing nociceptive stimulation Fornasari D. Clin Drug Investig. 2012;32 Suppl 1:45-52. Neuropathic pain: central sensitisation Normal sensory function AB fibre mechanoreceptor Innocuous stimulus Na+ channel Na+ channel Weak synapse Nonpainful sensation Increased nociceptor drive leads to central sensitization of dorsal horn neurons Innocuous stimulus Na+ channel Na+ channel Increased synapsis strength Central sensitisation occurs in inflammatory, functional and neuropathic pain Woolf CJ, et al. Lancet. 1999;353:1959-64. Painful sensation Neuropathic pain, central sensitisation and inflammation Neuropathic pain Central sensitisation (peripheral nerve damage) (neuropathic/inflammatory) a2-AR + Nav 1.8 Nav 1.9 Nav b3 TRPV1 ASIC Nav 1.9 Cava2d1 EP GABA Gly cold, hot, acid, mechanical 5HT3 a2-AR NK1 skin (skin, joint and viscera) DRG Cava2d1 Nav 1.8 Nav 1.3 Kv 1.4 TRPM8 DRG Inflammatory pain EP - PKC/A TRPV1 P2X3 B1/2 EP mGluR + PGE2 Inflammatory soup + NMDA dorsal horn neuron Brain (“pain”) http://www.uq.edu.au/pain-venom/about-pain. Accessed 7 May 2015. histamine, bradykinin, 5-HT, H+, prostaglandins, TNFa, NGF, ATP etc Types of cancer pain Chronic cancer pain: tumour-related pain Somatic pain Visceral pain Tumour-related bone pain: directly due to metastasis itself or oncogenic hypophosphataemic osteomalacia Peritoneal carcinomatosis Tumour-related soft-tissue pain like pleural pain/ear pain/eye pain Malignant perineal pain Paraneoplastic syndromes: hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, muscle cramps, Raynaud’s phenomenon Esin E, Yalcin S. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:599-618. Chronic intestinal obstruction Ureteric obstruction Chronic cancer pain: neuropathic pain Neuropathic pain syndromes Leptomeningeal metastases Trigeminal neuralgia Glossopharyngeal neuralgia Lumbosacral radiculopathy (damage to nerve root) Lumbosacral plexopathy (affecting a network of nerves) Cervical radiculopathy Brachial plexopathy Painful peripheral mononeuropathies Paraneoplastic sensory/motor/autonomic neuropathic pain Esin E, Yalcin S. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:599-618. Chronic cancer pain: treatment-related pain Surgery Chemotherapy Postmastectomy pain Painful peripheral neuropathy Post-thoracotomy pain Raynaud’s phenomenon Phantom limb/breast pain Chronic glucocorticoid-treatment complications Pain due to neck dissection Lymphoedema pain Radiotherapy Compression fractures due to osteoporosis Targeted therapy-related pain Late-onset brachial plexopathy Papulopustular rash Chronic radiation myelopathy Erythema Radiation enteritis Hand-foot skin syndrome Lymphoedema pain Paronychia Osteoradionecrosis Fingertip fissures Radiation dermatitis Eyelashes growth distortion Oral and anal mucositis Abdominal discomfort with diarrhoea Esin E, Yalcin S. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:599-618. Ripamonti C, et al. Ann Oncol. 2014; 25: 1097-106. Temporal classification of pain in cancer ACUTE PAIN follows injury to the body and generally disappears when the body injury heals. It is usually due to a definable nociceptive cause. It has a definite onset and its duration is limited and predictable (i.e. pain related to surgery, biopsy, pleurodesis, pathologic fracture, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, diagnostic and interventional procedures). It is often associated with objective physical signs of autonomic nervous system activity. Acute pain may also indicate a progression of disease and is often accompanied by anxiety. CHRONIC PAIN is due to the presence and/or progression of the disease and/or to treatments (i.e. chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and/ or osteoporosis, post- surgery, post- radiotherapy). Chronic pain may be accompanied by changes in personality, lifestyle, and functional abilities and by symptoms and signs of depression. Chronic pain with overlapping episodes of acute pain (i.e. breakthrough pain) is probably the most common pattern observed in patients with ongoing cancer pain. This indicates the necessity for monitoring the intensity of pain and associated symptoms and the analgesic treatments. Furthermore, the appearance of acute pain, or progression of a previously stable chronic pain, is suggestive of a change in the underlying organic lesion and requires clinical re-evaluation. Ripamonti CI, Bossi P. Cancer pain. Rehabilitation issues during cancer treatment and follow-up. ESMO Handbook, 2014. Cancer patients may have multiple types of pain Pain associated with cancer can be understood as multiple types of pain ≈80% Patients with cancer have ≥ 2 types of pain 33% Patients ≥ 4 types of pain However, patients with cancer can experience non-cancer pain simultaneously with cancer pain, such as pain from cancer treatment or unrelated conditions Pergolizzi JV, et al. Pain Pract. 2014 Dec 3. doi: 10.1111/papr.12253. [Epub ahead of print]. Incidence, assessment and burden of cancer pain Overall incidence of cancer pain 25 to 30% of patients with cancer report pain at the time of diagnosis 70 to 80% of advanced patients with cancer experience pain over the course of their disease, which is caused by tumour infiltration, treatment, or both Pergolizzi JV, et al. Pain Pract. 2014 Dec 3. doi: 10.1111/papr.12253. [Epub ahead of print]. Incidence of severe pain is high in ambulatory patients with newly diagnosed stage IV cancer Highest pain intensity score within one year of follow-up among newly diagnosed stage IV cancer patients, according to cancer type (n=505) None Low Moderate Severe 60 Percentage 50 40 30 20 10 0 Breast Thoracic Gastrointestinal Urogenital Head and Neck The incidence of severe pain pain is highest in gastrointestinal and head and neck cancers Isaac T, et al. Pain Res Manag. 2012; 17(5): 347–52. Other 40-year meta-analysis of patients with cancer pain Pooled prevalence rates of pain 100 90 Patients (%) 80 70 59% 64% 53% 60 50 33% 40 30 20 10 0 Patients after curative treatment (95% CI: 21% to 46%) Patients under anticancer treatment (95% CI: 44% to 73%) Patients characterised as advanced/metastatic/ terminal disease (95% CI: 58% to 69%) Patients at all disease stages (95% CI: 43% to 63%) Of patients with pain, more than one-third graded their pain as moderate or severe Pooled prevalence of pain was >50% in all cancer types with the highest prevalence in head/neck cancer patients (70%; 95% CI: 51% to 88%) CI= Confidence Interval van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, et al. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(9):1437-49. Incidence of pain by cancer type Cancers involving the pancreas, bone, brain, lymphoma, lung, head and neck are associated with a pain prevalence >85% 100 93 Percentage patients (%) 90 80 92 90 87 86 86 82 82 73 70 77 77 75 62 60 66 53 50 40 30 20 10 0 Cancer type Breivik H, et al. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(8):1420-33. Is pain in patients with haematological malignancies under-recognised? The results from Italian ECAD-O survey Solid tumours 59.4% Patients with moderate to severe pain No pain Low 16.4 Pts with ST Haematological cancers 67.3% Moderate 24.2 26.8 Severe 32.6 Pain in haematological malignancies deserves greater consideration 16.3 Pts with HT 0 16.3 20 36.7 40 30.6 60 Percentage Bandieri E, et al. Leuk Res. 2010;34(12):e334-5. 80 100 Prevalence of pain during the last 3 months of patients’ lives Prevalence of pain Prevalence of very distressing pain % 95% CI % 95% CI Head and neck 85.4 64.6-95.0 68.1 48.5-82.8 Oesophagus and stomach 88.4 81.0-93.2 62.9 52.3-72.4 Colon and rectum 84.8 77.7-89.9 64.9 57.3-71.9 Liver and bile ducts 73.7 63.6-81.8 56.1 46.4-65.3 Pancreas 80.3 68.6-88.4 67.0 54.5-77.6 Larynx, lung, and pleura 83.4 76.5-88.6 60.3 54.2-66.1 Breast 75.8 66.4-83.2 52.8 43.8-61.6 Female genital organs 89.9 76.9-96.0 69.2 52.7-82.0 Prostate 90.9 78.5-96.5 58.6 43.5-72.2 Bladder and kidney 89.3 76.1-95.6 70.4 56.6-81.2 Central nervous system 51.9 27.4-75.5 21.1 9.2-42.4 Lymphoma and leukaemia 83.0 73.6-89.5 63.4 53.0-72.7 Multiple myeloma 86.1 66.4-95.1 66.3 41.4-84.6 Other and unspecified 77.6 69.8-83.8 62.9 55.2-70.0 Primary tumour 1,271 oncology patients with 3 months of life expectancy. Pain was seen in: 82.3% of patients Haematological patients presented with pain as frequently as those with solid tumours Costantini M, et al. Ann Oncol. 2009; 20: 729-35. p = 0.098 p = 0.035 Breakthrough cancer pain: a pan-European survey European survey of 5,084 patients with cancer across 11 countries and Israel 100 90 80 Patients (%) 70 60 69% 56% 50% 44% 50 40 30 20 10 0 Experienced moderate to severe pain at least once a month Described pain as severe Breivik H, et al. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(8):1420-33. Reported painrelated difficulties with everyday activities Believed that their quality of life was not considered a priority in their overall care by their health care professional The reported prevalence of breakthrough cancer pain varies widely Prevalence of breakthrough pain in studies applying standard criteria for breakthrough pain Study Type of population Prevalence of breakthrough pain Portenoy & Hagen, 1990 Hospital inpatients (pain team referrals) – USA n = 90 63% Fine & Busch, 1998 Hospice homecare patients – USA n = 22 86% Portenoy et al, 1999 Hospital inpatients – USA n = 178 51% Zeppetella et al, 1999 Hospice inpatients – UK n = 414 89% Fortner et al, 2002 Cancer patients (home setting) – USA n = 1000 63% The prevalence of breakthrough pain has been reported to be 19–95% amongst various groups of patients, reflecting differences in the definition and methods utilised, and in the populations studied Davies A. Cancer-related breakthrough pain. Oxford University Press 2012. Universal pain assessment tools Verbal Pain Intensity Scale No pain Mild pain Moderate pain Severe pain Very severe pain Worst possible pain 3 4 5 6 Faces Pain Scale – Revised (FPS-R) 1 2 National Pharmaceutical Council. http://www.npcnow.org/publication/pain-current-understanding-assessment-management-andtreatments. Accessed 8 Jun 2015. Ripamonti CI. Ann Oncol. 2012;23 Suppl 10:x294-301. Validated assessment tools for the assessment of pain Visual analogue scale VAS 10 cm No pain Worst pain Verbal rating scale VRS 1 No pain 2 Very mild 3 4 Mild 5 Moderate 6 Severe Very severe Numerical rating scale NRS No pain 0 1 2 3 4 5 Ripamonti CI, et al. Ann Oncol. 2012 Oct;23 Suppl 7:vii139-54. 6 7 8 9 10 Worst pain Cancer pain can add additional burden to patients Cancer pain can be exacerbated by the normal worries that accompany cancer diagnosis ANXIETY DEPRESSION CATASTROPHISING HOPELESSNESS CONCERNS ABOUT FINANCES WORRIES OVER FAMILIAL SUPPORT Pergolizzi JV, et al. Pain Pract. 2014 Dec 3. doi: 10.1111/papr.12253. [Epub ahead of print]. Cancer pain affects many aspects of daily life 100 90 80 Patients (%) 60 69% 67% 70 52% 51% 50 40 30% 30 20 10 0 Pain impacts work performance Described pain as distressing Pain creates difficulty in performing normal activities in daily life Breivik H, et al. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(8):1420-33. Pain stops them from concentrating or thinking Being in too much pain to be able to care sufficiently for themselves BTcP affects all areas of daily life Interference with various aspects of daily living 2nd quartile 3rd quartile Enjoyment of life Sleep Relations with other people Normal work Walking ability Mood General activity 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Numerical rating (0-10) BTcP has a significant negative effect on quality of life that is related to a direct effect (suffering) and an indirect effect (interference with activities of daily living) Study of 1000 cancer patients from 13 European countries. Davies A, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(5):619-28. National Breakthrough Pain Study Interview of 2198 patients with opioid-treated chronic pain 80% of patients reported BTP Patients had a median of 2.0 episodes of BTP per day (range, 1-50) and a median duration of BTP of 45 minutes (range, 1-720) Compared with patients without BTP, patients with BTP had more pain-related interference in function, worse physical health and mental health, more disability and worse mood BTP is highly prevalent and associated with negative outcomes Narayana A, et al. Pain. 2015;156(2):252-9. There are many barriers to better control of cancer pain Tendency to trivialise pain in light of seriousness of cancer Fear to talk about pain, thinking it means their conditions is worsening Failure to diagnose breakthrough pain Patientrelated barriers Unwillingness to report pain for any number of reasons, including not wanting to distract the doctor from fighting the cancer Lack of availability of opioid analgesics in some countries/ regions Clinicianrelated barriers Multidisciplinary teams led by oncologists who focus on cancer treatment and regard pain as a secondary matter Barriers to pain control Healthcaresystem-related barriers Inadequate pain assessment Costs Absence of national policies on opioid use and no prioritisation of pain control in public health Pergolizzi JV, et al. Pain Pract. 2014 Dec 3. doi: 10.1111/papr.12253. [Epub ahead of print]. Rate of undertreated cancer pain (%) Little progress has been made in adequate treatment of cancer pain 80 70 60 50 40% 40 33% 30 20 10 0 1994 2012 Year Pergolizzi JV, et al. Pain Pract. 2014 Dec 3. doi: 10.1111/papr.12253. [Epub ahead of print]. The many consequences of undertreatment of cancer pain Insomnia and other sleep disturbances Profound fatigue Anorexia Physical consequences Various forms of incapacity Reduced cognition Withdrawal from social and familial interactions Feelings of isolation Psychological consequences Reduced coping skills Pergolizzi JV, et al. Pain Pract. 2014 Dec 3. doi: 10.1111/papr.12253. [Epub ahead of print]. Suffering Other psychological distress existential and spiritual Challenges in management of cancer pain Pain management primarily involves medical oncologists Other, 5 Physiotherapist, <1 None, 3 Radiation oncologist, <1 Anaesthetist, <1 Don’t know, 1 Nurse/Specialist nurse, 1 Neurologist, 1 Palliative care specialist, 2 Pain specialist, 3 Obstetrician/gynaecologist, 1 Haematologist, 4 General surgeon, 4 Medical doctor, 8 GP/Primary care provident, 19 Breivik H, et al. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(8):1420-33. Medical oncologist, 42 Patients believe that healthcare providers give inadequate attention to pain management 60 50% Patients (%) 50 38% 40 33% 26% 30 20 27% 12% 10 0 HCP does not consider patient QoL to a great extent HCP does not recognise pain as a problem HCP treats cancer rather than pain Breivik H, et al. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(8):1420-33. HCP does not have time to discuss pain HCP does not know how to control pain HCP does not always ask about pain A multidisciplinary approach is preferred in management of cancer pain NEUROLOGIST PAIN SPECIALIST ONCOLOGIST GENERAL PRACTITIONER PALLIATIVIST RADIOTHERAPIST Ideally, there should be communication among the various specialists, with oncologists often coordinating the patient’s care. Pergolizzi JV, et al. Pain Pract. 2014 Dec 3. doi: 10.1111/papr.12253. [Epub ahead of print]. Patient adherence to pain guidelines remains insufficient In a study of 193 inpatients, 109 met the inclusion criteria of which 70 were guideline adherent and 39 non-adherent 63% of patients initiated on NCCN adherent guidelines obtained analgesia at 24 hours vs. 41% in the non-adherent group Average pain scores across the 24-hour period were lower in the adherent compared with the non-adherent group (3.5 vs. 4.4) Chronic home opioid exposure was significantly associated with non-adherent therapy (OR=3.04; P=0.01) and achievement of analgesia at 24 hours Mearis M, et al. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(3):451-8. Medical oncologists do not always follow practice guidelines on pain management In a survey of 268 medical oncologists (24% completers): – Adherence to the different recommendations of the guideline ranged from 18 to 100% Adhered to prescribing paracetamol as first-line pain treatment 94% Prescribed a laxative in combination with opioids to prevent constipation 100% Adhered to the guideline when first-line treatment had insufficient effect 24% Adhered to recommendations for insomnia treatment 35% Adhered to the recommendation to perform a multidimensional pain assessment when disease worsens and pain increases 18% 0 10 20 30 40 50 Percentage te Boveldt N, et al. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(5):1409-20. 60 70 80 90 100 Combined pain consultation and pain education programmes can improve outcomes In oncology outpatients randomly assigned to SC (n=37) or PC-PEP (n=35): The overall reduction in pain intensity and daily interference was significantly greater after randomisation to PC-PEP than to SC (average pain 31% vs. 20%, P=0.03; current pain 30% vs. 16%, P=0.016; interference 20% vs. 2.5%, P=0.01) Patients were more adherent to analgesics after randomisation to PC-PEP than to SC (P=0.03) PC-PEP improves pain, daily interference and patient adherence SC, stanard care; PC-PEP, pain consultation and pain education programme Oldenmenger WH, et al. Pain. 2011;152(11):2632-9. Summary Cancer pain may be nociceptive, neuropathic, or mixed Cancer pain is often under-recognised and undertreated Cancer pain adds additional suffering to patients, affecting many areas of daily life More adequate management of cancer pain is needed through a multidisciplinary approach