Powerpoint Template - Cancer and Hematology Centers

advertisement

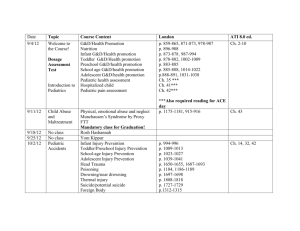

Pediatric Oncology for the Primary Care Provider Kate A. Mazur, MSN, RN, CPNP Texas Children’s Hospital Advanced Practice Provider 1st Annual Conference Houston, TX February 8, 2014 Objectives • Review the incidence of childhood cancer • Describe the most common childhood malignancies, with a focus on initial evaluation and diagnosis, red flags, and when to refer to specialist • Analyze the unique precautions for patients with oncologic illnesses The Scope of the Problem • 13,400 children ages birth to 19 years are diagnosed with cancer each year • Cancer is the #1 cause of disease-related death in children Source: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, 1975-2003, Div. of Cancer Control and Pop. Sciences, NCI, 2006 The Good News… • Overall 5 year survival rate across all cancers is now 80% • Estimated 270,000 childhood cancer survivors in the U.S. • However, two-thirds of survivors face at least one chronic health problem • 25% of survivors face a late effect from treatment that is classified as severe or lifethreatening Where do I start? • Early diagnosis and initiation of treatment is imperative to improved survival • Diagnosis of cancer starts with a thorough history and physical • Most symptoms of childhood cancer due to either a mass, its effect on the surrounding tissues, invasion of the bone marrow, or secretion of a substance by the tumor that disturbs normal functions • Most common presenting signs and symptoms of many malignancies include weight loss, failure to thrive, anorexia, malaise, fever, pallor, and lymphadenopathy High Risk Patients • Familial cancer pre-disposition syndromes – Li-Fraumeni Syndrome – Familial adenomatosis polyposis – Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome • Family history of cancer – Retinoblastoma • Autoimmune diseases in patient or family • Down Syndrome • Neurofibromatosis Type 1 • HIV/AIDS Leukemia • Cancer of the bone marrow • Uncontrolled proliferation of immature white blood cells (“blasts”) • Most common type of cancer in children and adolescents under 20 years of age (~30%) • Incidence • – 4900 new cases each year – Males > Females; Hispanics > Caucasians > African Americans – Peak age 2-5 years Risk factors – Down Syndrome: 14-fold increase – Klinefelter Syndrome – Fanconi anemia – Immunodeficiencies: ataxia telangiectasia, Wiskott-Aldrich, Bloom syndrome – Past exposure to chemotherapy or ionizing radiation Most Common Types of Childhood Leukemia • Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) ~ 80% • Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) ~ 15% • Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) ~ 5% Leukemia: Presenting Signs and Symptoms • Relate to the infiltration of the bone marrow • History – Fatigue – Persistent fevers – Bone pain – Anorexia – Weight loss – Recurrent infections • Physical Exam – Pallor – Bleeding, bruising, or petechiae – Hepatosplenomegaly – Lymphadenopathy Lymphadenopathy: When to Worry • Supraclavicular, axillary, or epitrochlear adenopathy • Adenopathy that persists longer than 6 weeks or is increasing in size • Asymmetric lymphadenopathy • Leukemia usually presents with generalized lymphadenopathy; localized LAD more likely to be infectious in origin • Malignant nodes generally hard and nontender; infectious/inflammatory nodes usually tender, freely moveable, overlying erythema • For localized cervical adenitis with inflammation and fever, treat with ONE course of antibiotics, if no response refer • DO NOT START STEROIDS Leukemia: Initial Diagnostic Tests • CBC with manual differential, reticulocyte count, and peripheral blood smear • Chem 10: Electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, Ca2+, Mg2+, PO4-, uric acid, LDH – Hypocalcemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, hyperuricemia may indicate tumor lysis syndrome oncologic emergency – Elevated LDH (non-specific tumor marker) • Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy is the only definitive diagnostic test – Done by oncology service only Complete Blood Count: A Review • White blood cells/Neutrophils – Responsible for fighting infection • Red blood cells/Hemoglobin – Carries O2 from lungs to blood tissues and CO2 from tissue to lungs • Platelets – Necessary for clotting and control of bleeding CBC Findings in Leukemia • Leukocytosis - ~50% with WBC >10,000 and ~20% > 50,000 – Elevated blasts and low neutrophils • Anemia • Thrombocytopenia • 2 or more cell lines decreased REFER – 90% present with hemoglobin < 11g/dL, 45% < 7g/dL – 75% present with platelets < 100,000/mm3 Lymphoma • Tumor of the lymphatic system • Incidence – 1500 new cases each year – More common in adolescents and older teenagers, males, Caucasians • Risk factors – Immunodeficiency syndromes: Wiskott Aldrich, SCIDS, HIV/AIDS – Autoimmune diseases: RA, SLE – Some viruses: Epstein-Barr (particularly for Burkitt’s lymphoma) Types of Lymphoma • Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma – 60% – – – – Lymphoblastic Anaplastic Burkitt’s Diffuse large B-cell • Hodgkin’s Lymphoma – 40% Lymphoma: Presenting Signs and Symptoms • History – 75% asymptomatic – Unexplained fever for more than 3 days – Weight loss of 10% within 6 months – Drenching night sweats – Malaise – Anorexia • Physical Exam – based on location of disease – Head/Neck: supraclavicular or cervical adenopathy, jaw swelling, unilateral tonsillar enlargement – Abdomen: splenomegaly, abdominal distention, jaundice – Mediastinum: cough, chest pain, stridor Lymphoma: Evaluation and Diagnostic Work Up • DO NOT START STEROIDS • Blood work: CBC w/diff, liver and renal fxn tests, including alkaline phosphatase; ESR, ferritin, LDH may be elevated • Imaging Studies – CT scans (neck, chest, abdomen, pelvis) – PET scan – Bone scan • Biopsy of affected node – Required for definitive diagnosis – Done under guidance of oncology team only Brain Tumors • Can be malignant or “benign” • Much slower rate of treatment advances than other malignancies • Unique challenges in children – brain still developing • Incidence – 3400 new cases every year – More common in ages < 15 years • Risk factors – Little known – Hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes (i.e. Li-Fraumeni Syndrome) Most Common CNS Tumors • Astrocytoma – Most supratentorial but can originate in cerebellum, brainstem, or hypothalamus • Brain Stem Glioma – Medulla, pons • Medulloblastoma – Cerebellum • Ependymoma Picture from The Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, http://www.montekids.org/services/neurosurgery/neurologicaldisorders/brain_tu mor/ – Ependymal tissue within the ventricular system, most commonly the fourth ventricle CNS Tumors: Presenting Signs and Symptoms • Depends on site and severity of disease as well as child’s age & development • History – Seizures – Visual changes – Headache – Nausea/vomiting, often in morning – Poor concentration or mental status change • Physical Exam – Hemiparesis – Endocrinopathies – Ataxia – Cranial nerve deficits Headache: When Further Evaluation is Warranted • • • • • • • • • Recurrent morning headache Headache that awakens the child Intense, incapacitating headache Changes in the quality, frequency, or pattern of headaches Presence or onset of neurologic abnormality Ocular findings such as papilledema, decreased visual acuity, or loss of vision Associated with vomiting that is persistent, increasing in frequency, or preceded by recurrent headaches Age 3 years or less DO NOT START STEROIDS CNS Tumors: Diagnostic Tests • Imaging studies are the only diagnostic tests • MRI brain and spine • CT often obtained first due to easy access • LP if clinically indicated and safe to perform Solid Tumors: Evaluation of an Abdominal Mass • ALWAYS suspect a malignant solid tumor in a child with a palpable abdominal mass • Avoid abdominal palpation as much as possible; palpate gently if necessary • In younger children, often renal neuroblastoma or Wilms’ tumor • In older patients, may be related to leukemia or lymphoma with enlargement of the spleen or liver • Obtain comprehensive GU and GI histories • Associated symptoms of flushing, palpitations, diarrhea, failure to thrive, and fever could point to disseminated process such as neuroblastoma • Complete exam with focus on skin, extremities (bone pain), neuro exam (Horner’s syndrome, spinal cord compression), organomegaly, measurement of abdominal girth • Obtain diagnostic imaging STAT – Usually start with abdominal ultrasound Wilm’s Tumor • Large, rapidly growing, vascular renal tumor • Second most common intra-abdominal malignancy in children • Can be bilateral or unilateral • Incidence • – 500 new cases/year – Peak incidence 3 years of age – Slight female predominance; African-Americans > Caucasians > Asians Risk factors – Congenital anomalies: GU malformations, hemihypertrophy, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Denys-Drash syndrome – Familial pre-disposition syndromes: Li-Fraumeni syndrome Wilm’s Tumor: History and PE Findings • Abdominal mass – smooth, firm, rarely crosses midline but 510% are bilateral • Diffuse abdominal distention with large masses • Usually asymptomatic, but 25% have abdominal pain, vomiting, hematuria, hypertension • Signs of thrombosis: leg swelling, prominent veins over abdomen • Signs of hemorrhage into tumor (occurs rarely): anemia, fever, rapid abdominal distension Wilm’s Tumor: Diagnostic Tests • Blood work – CBC, liver function, renal function • Coagulation screen – may acquire Von Willebrand’s • Abdominal ultrasound usually first test ordered – will reveal mass arising from within kidney • Doppler US to assess patency of renal vein and inferior vena cava • Abdominal CT Neuroblastoma • Cancer of the sympathetic nervous system; derived from neural crest cells • Second most common solid tumor of childhood and the most common extracranial solid tumor • Incidence • – 650 new cases every year in the U.S. – 90% cases in children < 5 years old – Boys > girls; Caucasian predominance Risk factors – Most cases sporadic – Has been identified in other disorders of neural crest cells • Neurofibromatosis • Hirschsprung’s disease • Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome • DiGeorge syndrome Neuroblastoma: Clinical Presentation • Can arise anywhere along sympathetic nervous system • Signs and symptoms depend on location of primary tumor and presence of metastasis • Two-thirds have primary site in abdomen, usually adrenal • Thoracic region is the next most common primary site • About 60% have metastatic disease at presentation due to vague initial symptoms and late presentation – Bone marrow – Bone – Liver – Skin – Orbits Neuroblastoma: Presenting Signs and Symptoms • • • • • • • • • • • Firm, irregular, non-tender abdominal mass Hepatomegaly Abdominal pain Urinary obstructions Flushing Sweating Diarrhea Anorexia Malaise Site-specific symptoms from metastases to bone, skin, liver, or CNS Opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome – “dancing eyes and dancing feet” Neuroblastoma: Presenting Signs and Symptoms Neuroblastoma: Diagnostic Tests • • • • • • • • CBC – cytopenias Chem 10 Ferritin, LDH, uric acid Liver panel Urine catecholamines (VMA/HVA) CT chest/abdomen/pelvis Tissue biopsy for definitive diagnosis Bilateral bone marrow aspirate and biopsy to evaluate for BM involvement • MIBG scan or bone scan to evaluate for metastasis MIBG Scan Osteosarcoma • Tumor of the bone; usually at the end of long bones • Incidence – 400 new cases/year – More prominent during adolescent growth spurt; periods of rapid bone growth – Males > females; African-Americans > Caucasians • Risk factors – Ionizing radiation – Hereditary retinoblastoma – Li-Fraumeni Syndrome Osteosarcoma: Signs and Symptoms • • • • • Dull, aching pain, usually worse at night +/- soft tissue swelling, warmth May have vascularity over the mass Decreased range of motion Often long duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis; can be up to 6 months Osteosarcoma: Diagnostic Tests • Diagnostic Imaging – Plain radiograph of affected area – “sunburst pattern” – MRI to further examine tumor boundaries, soft tissue component, relationship to joints, blood vessels, neurovascular bundle – Chest XR or CT to evaluate for mets – Bone scan to evaluate for skeletal mets • Blood Tests – Elevations in LDH, alk phos may be present • Tumor Biopsy – Necessary for definitive diagnosis Supportive Care of a Patient with Cancer Infection Prophylaxis • Good hand washing!! • Proper dental hygiene – daily brushing with a soft brush, use of chlorhexidine mouth rinse • Avoidance of crowded, enclosed spaces • Cleanliness of perirectal area – avoid constipation • No rectal temperatures! • Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) from time of diagnosis until 6 months after completion of therapy – Trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole, Pentamidine, Dapsone • Viral and fungal prophylaxis may be indicated Management of Fever in the Child with Cancer • Defined as a single temperature of ≥ 101°F or two temperatures ≥ 100.4°F taken 1 hour apart • Do not give anti-pyretics! • No rectal temperatures • Every cancer patient who presents with fever should be considered septic until proven otherwise • Prompt evaluation and management essential for improved survival • Goal is to administer first dose of IV antibiotics within 1 hour of presentation Initial Evaluation of Fever • Prompt tx essential – send to ER or urgent care center for immediate evaluation and management and call oncology service • Evaluate for signs of septic shock – Tachycardia – usually the first sign of shock. Ideally, aggressive treatment starts here. – Check perfusion – delayed capillary refill; pulses weak and thready or bounding – Hypotension – LATE sign – Mental status changes; lethargy – OMINOUS • Examine for focal signs of infection – Often there are none – Oral cavity, perianal area, skin, respiratory tract, abdomen (typhlitis) Fever: Diagnostic Work Up • CBC with differential – risk-based management based on neutrophil count • Blood cultures – all CVC lumens and peripheral; important to have prior to first dose of antibiotics • Urinalysis/urine culture, if feasible based on clinical status – no catheterization • Additional cultures of any potential sources of infection – skin lesions, stool sample if diarrhea, mouth sores • Do NOT I & D any skin lesions • Chest XR if respiratory symptoms – obtain portable or delay until after initial antibiotics • Do NOT perform LP until oncology service is consulted Empiric Therapy of the Febrile Patient • DO NOT wait for culture results • Broad-spectrum antibiotics must be started immediately; will tailor antibiotic choice when culture results known • Antibiotics chosen based on individual institution’s local microbial prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility patterns • Regimen also based on risk criteria – high risk if ANC < 100, infant ALL, AML, in any phase of leukemia tx other than maintenance (induction at highest risk), < 7 days from last chemotherapy, focal signs of infection, or concern for sepsis • Admission often indicated • Anti-virals and/or anti-fungals may be added as clinically indicated • Septic shock treated aggressively with normal saline fluid boluses and triple antibiotics Immunizations and the Cancer Patient • Cannot assume adequate immunization even if patient’s vaccines are up to date prior to diagnosis • NO LIVE VACCINES • Siblings or household contacts should not receive the oral polio vaccine • All other vaccines may continue as scheduled, but will need to check titers at completion of treatment to ensure adequate immunity. Boosters or full re-immunization may be needed after completion of therapy • Highly recommend seasonal influenza vaccination in patient and household contacts References • Howlader N. et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2013. • Hastings, C. (2002). The Children’s Hospital Oakland Hematology/Oncology Handbook. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, Inc. • Kline, N. & Tomlinson, D. (2005). Pediatric Oncology Nursing. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Publishing. • Lowry, A., Bhakta, K., & Nag, P. (2011). Texas Children’s Hospital Handbook of Pediatrics and Neonatology. McGraw-Hill Publishing. • Pizzo, P. & Poplack, D. (2005). Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology, 5th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. • Zorc, J. (2013). Clinical Handbook of Pediatrics, 5th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. Questions??