Rethinking the Treatment of Older Adults With Acute

advertisement

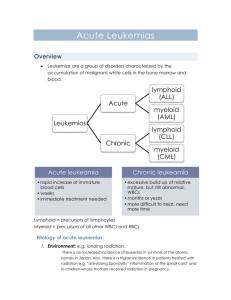

Rethinking the Treatment of Older Adults With Acute Myeloid Leukemia Mark J. Levis, MD, PhD Associate Professor of Oncology The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center Johns Hopkins University Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest Mark J. Levis, MD, PhD, discloses that he has served as an advisor/consultant for Teva Pharmaceuticals and Ambit Biosciences Corp. Unapproved Use Disclosure The University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and i3 Health require CME faculty (speakers) to disclose to attendees when products or procedures being discussed are off-label, unlabeled, experimental, and/or investigational (not FDA approved), and any limitations on the information that is presented, such as data that are preliminary or that represent ongoing research, interim analyses, and/or unsupported opinion. Dr. Levis discloses that he will discuss off-label uses of decitabine and sorafenib. Learning Objectives Assess methods to classify and determine the prognosis of older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Explain how patient characteristics and risk stratification affect treatment selection Evaluate efficacy and safety data on existing and novel therapies for older adults with AML AML: Scope of the Problem • Annual US diagnoses: 7,820 • Annual US deaths: 5,930 • Annual US diagnoses: 6,770 • Annual US deaths: 4,440 AML is a clonal malignant proliferation of myeloid blast cells in the marrow with impaired normal hematopoiesis. Siegel et al, 2013. Age-Specific AML Incidence Rates 200 180 160 Incidence 140 120 Males Females 35-39 40-44 All 100 80 60 40 20 0 16-24 25-29 30-34 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 Patient Age (yrs) Juliusson et al, 2009. 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 90+ MRC Trials: Younger Adults 15 to 59 Years (n=7,704) MRC = United Kingdom Medical Research Council. Burnett, 2012. MRC Trials: Older Adults 60+ Years (n=3,541) Burnett, 2012. Traditional Paradigm for the Treatment of AML Complete response Induction therapy Consolidation chemotherapy Allogeneic transplant Relapse? Complete response? Primary refractory Salvage therapy Modern Paradigm for the Treatment of AML Complete response Risk Stratify Allogeneic transplant Consolidation chemotherapy Risk Stratify Induction therapy Primary refractory Relapse? Salvage therapy Complete response? Common Induction Regimens Used in Adult Patients With AML Agents Doses “7 + 3” induction Cytarabine (100–200 mg/m² infusion x 7 d) and anthracycline (daunorubicin, idarubicin, or mitoxanrone x 3 d) Intensified induction Various combinations of Ara-C, etoposide, anthracycline (ICE, ADE, IA, etc.) Low-dose Ara-C 20 mg bid for 10 d Azacitidine 75 mg/m2 daily for 5–10 d Decitabine 20 mg/m2 daily for 5 d Ara-C = cytarabine; ICE = idarubicin/cytarabine/etoposide; ADE = daunorubicin/cytarabine/etoposide; IA = idarubicin/cytarabine. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), 2013. Common Consolidation Regimens Used in Adult Patients With AML Agents Doses “HiDAC” (4 cycles) Cytarabine (3,000 mg/m²) infused over 3 hrs bid on Days 1, 3, and 5 Allogeneic transplant Either myeloablative or nonmyeloablative, with an HLA-matched or alternative donor Low-dose Ara-C 20 mg bid for 10 d at 4–6 wk intervals Azacitidine 75 mg/m2/d for 5–10 d, repeated monthly Decitabine 20 mg/m2/d for 5 d, repeated monthly Hi-DAC = high-dose cytarabine; HLA = human leukocyte antigen. NCCN, 2013. How do older patients with AML fit into this modern paradigm? AML Therapy in Elderly Americans Age group (yrs) 85 65–74 75–84 1,132 1,082 443 2,657 Received chemotherapy (%) 44 24 6 30 Hospitalized (%) 89 91 83 89 Hospital/SNF days (%) 33 30 27 31 Median survival (mos) 3 2 1 2 15 19 20 17 N Hospice (%) SNF = skilled nursing facility. Menzin et al, 2002. Total Survival in Elderly AML by Therapy 3,317 elderly patients aged ≥65 years with AML 1,193 (36%) received chemotherapy (younger, fewer comorbidities) 888 patients matched in both cohorts Survival Median (mos) 1-Yr (%) Overall 4.4 NA Chemotherapy 6.1 30 No therapy 1.7 10 NA = not applicable. Menzin et al, 2006. Supportive Care Is Effective but Insufficient as a Primary Treatment Symptom Treatment Fungal infections Azole antifungals (posaconazole, voriconazole, echinacandins, amphotericin-B) Bacterial infections Broad-spectrum antibiotics Viral infections Acyclovir, valacyclovir Leukocytosis Hydroxyurea Neutropenia G-CSF (filgrastim), GM-CSF (sargramostim) during post-remission therapy Anemia/thrombocytopenia Tumor lysis syndrome Cognitive decline Leukocyte-depleted products for transfusion and irradiated blood products for patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy; screen for cytomegalovirus Prophylaxis with intravenous hydration with diuresis, urinary alkalinization, allopurinol; treatment with rasburicase Patient monitoring for nystagmus, dysmetria, slurred speech, and ataxia before each dose of cytarabine Nausea/vomiting Serotonin receptor antagonists (ondansetron) Ocular toxicity Saline or steroid drops in both eyes during cytarabine therapy Oral mucositis Mouthwash with viscous lidocaine, Maalox, and injectable diphenhydramine NCCN, 2013; Rogers, 2010; Higa et al, 1991; Jabbour et al, 2006; Harris et al, 2008. “Standard” Chemotherapy vs. Nonintensive DNR + Ara-C vs. “watch and wait” (hydroxyurea) – CR in 58% vs. 0% – Median survival: 21 vs. 11 weeks – Survival at 2.5 years: 13% vs. 0% Ara-C SQ 20 mg/m2 for 21 days vs. “7 + 3” – CR with “7 + 3”: 52% vs. 32% – induction death with “7 + 3”: 31% vs. 10% – Similar survival and CR duration DNR = daunorubicin; CR = complete response; SQ = subcutaneously. Lowenberg et al, 1989; Tilly et al, 1990. Pts considered for remission induction therapy (%) Intention to Induce by Age and Region (Swedish Registry) Region Pts = patients. Juliusson et al, 2006. Survival Among Patients Ages 70–79 (region, sample size) APL = acute promyelocytic leukemia; RI = resistive index. Juliusson et al, 2006. Low-Dose Ara-C vs. Hydroxyurea ± ATRA in Elderly AML or High-Risk MDS 217 elderly patients aged ≥60: 155 aged ≥65 years, 58 secondary AML, 30 high-risk MDS Ara-C 20 mg bid x 10 every 4–6 weeks vs. hydroxyurea na CR (%) 1-Year OS (%) aData Ara-C 102 18 27 not available for all patients. ATRA = all-trans retinoic acid; MDS = myelodysplastic syndromes. Burnett et al, 2007. Hydroxyurea 99 1 3 P NA 0.00006 0.0009 Conventional vs. Escalated-Dose Daunorubicin Daunorubicin Daunorubicin 45 mg/m2 90 mg/m2 No. (%) No. (%) 411 402 Age, median [range] (yrs) 67 [60–79] 67 [60–83] WHO PS 0 or 1 363 (88) 354 (88) 43 (10) 42 (10) 98 (24) 82 (21) 221 (54) 259 (64) 49 (12) 44 (11) Total patients (n) PS 2 Unfavorable cytogenetics CR Early death WHO = World Health Organization; PS = performance status. Lowenberg et al, 2009. Conventional vs. Escalated-Dose Daunorubicin, Survival by Age Lowenberg et al, 2009. Conventional vs. Escalated-Dose Daunorubicin, Survival by Age (cont.) Lowenberg et al, 2009. Frontline Azacitidine • Sample of 165 patients treated with azacitidine 75 mg/m2 ± VPA and ATRA ; 32% had 20%–29% marrow blasts • Median age, 74 yrs (31–91); 83% 65 years; median cycles, 4; median follow-up, 16 mos Response CR + CRi No. (%) 19 + 3 (13) PR 10 (6) HI 28 (17) 19% • Median response duration, 6.9 months • Median survival, 9.4 months; 1-year OS, 37% VPA = valproic acid; ATRA = all trans retinoic acid; CRi = complete response with incomplete hematologic recovery; PR = partial response; HI = hematologic improvement. Thépot et al, 2009. Azacitidine Prolongs Survival in WHO-Defined AML 113 older patients with 20%–29% blasts (WHO AML) Median age 70 years; poor cytogenetics 24% 55 randomly assigned to AZA, 58 to conventional care regimens (IC 11, LDAC 20, BSC 27) Median follow-up, 20 months; median cycles, 8 (1–39) Parameter AZA CCR P value CR (%) 18 16 NS Median OS 24.5 16.0 0.005 Hospitalization (pt/yr) 3.4 4.3 0.03 Infection (pt/yr) 0.58 1.14 0.003 AZA = azacitidine; IC = intensive chemotherapy; LDAC = low-dose cytarabine; BSC = best supportive care; CCR = conventional care regimen; NS = not significant. Fenaux et al, 2010. Initial Conclusions Modern AML treatment requires risk stratification at multiple time points Treatment confers a survival benefit over supportive care, even in older AML patients Risk Stratification (Questions to Consider for Each Patient) Will the patient survive treatment? How likely is it that a patient will achieve remission? – What type of induction therapy should be used? If a remission is achieved, will the patient benefit from consolidation? – What type of consolidation therapy should be used? Thirty-Day Mortality of AML Induction Therapy: Effect of PS Age (yrs) <56 PS 56–65 66–75 >75 Early Death (%) 0 2 11 12 14 1 3 5 16 18 2 2 18 31 50 3 0 29 47 82 Appelbaum et al, 2006. Proportion of AML (Non-APL) Patients, PS 0 to 4 at Diagnosis Pts per WHO performance status (%) 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% WHO 0 WHO I 50% WHO II WHO III 40% WHO IV Missing 30% 20% 10% 0% 16-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 85-89 Age (yrs) Juliusson et al, 2009. 90+ All Prognostic Model: MD Anderson CR Rate 8-Wk Mortality 1-Yr Survival Age ≥75 yrs ■ ■ ■ Poor performance status ■ ■ ■ Unfavorable karyotype ■ ■ ■ Anemia ■ Leukocytosis ■ Antecedent hematologic disease ■ ■ ■ Creatinine >1.3 mg/dL ■ ■ ■ Prognostic Factor ■ Elevated lactate dehydrogenase Treated in laminar flow room Kantarjian et al, 2006. ■ ■ ■ Prognostic Model Predicts Survival 0 1–2 ≥3 121 568 301 Survival, median (mos) 1-yr (%) 2-yr (%) 18 63 35 7 33 19 1 9 3 CR (%) 72 51 24 8-wk mortality (%) 10 26 57 Survival n Kantarjian et al, 2006. Cytogenetic Risk Categories Unfavorable Favorable 1. Complex karyotype 2. Monosomy karyotype 3. Deletion of 5 or 7 4. t(6;9) 5. inv(3) 6. 11q23 (MLL gene) 1. inv(16) 2. t(8;21) 3. t(15;17) Intermediate Everything else MLL = mixed lineage leukemia; inv = inversion; t = translocation. Grimwade et al, 2001; Slovak et al, 2000. Unfavorable Risk Cytogenetics Increase With Age 100% 35 39 39 55 56 51 Incidence of pts with risk cytogenetics 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 48 Unfavorable Intermediate 40% 45 30% 20% 10% 17 6 0% <55 56-65 Age (yrs) Appelbaum et al, 2006. 5 4 66-75 >75 Favorable Molecular Risk Categories FLT3/ITD NPM1 mutations = unfavorable risk mutations = favorable risk – In the absence of a FLT3/ITD mutation CEBPA mutations = favorable risk – In the presence of double mutations C-KIT mutations = unfavorable risk – In the context of core binding factor AML FLT3 = fms-related tyrosine kinase 3; ITD = internal tandem duplication; NPM1 = nucleophosmin; CEBPA = CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, alpha; C-KIT = type III tyrosine kinase growth factor receptor. Kottaridis et al, 2001; Dohner et al, 2005; Taskesen et al, 2011; Paschka et al, 2006. AML Categories Defined by Cytogenetic and Molecular Abnormalities in All Adults NPM1c Other int. risk CEBPA FLT3/ITD CBF (inv[16], t[8;21]) Poor-risk cytogenetics (5q-; 7q-; inv[3], complex, etc.) NPM1c = mutated nucleophosmin; CBF = core-binding factor; int. = intermediate. Kottaridis et al, 2001; Dohner et al, 2005; Taskesen et al, 2011; Paschka et al, 2006. APL AML Categories Defined by Cytogenetic and Molecular Abnormalities in Older Adults NPM1c Other int. risk CEBPA FLT3/ITD CBF (inv16, t8;21) APL Poor-risk cytogenetics (5q-; 7q-; inv[3], complex, etc) Kottaridis et al, 2001; Dohner et al, 2005; Taskesen et al, 2011; Paschka et al, 2006. Karyotype Influence on Patient Survival (%) Karyotype Significantly Impacts CR and OS in Elderly AML 100 90 80 Favorable (7%): t(15;17), t(8;21), inv(16) 72 70 60 Intermediate (79%): normal, all others 53 50 34 40 Unfavorable (14%): complex (>5 abnormal) 26 30 15 20 10 2 0 Grimwade et al, 2001. CR OS (5-year) DFS and OS of Patients Age ≥60 Years (A and B) and Age ≥70 Years (C and D) With Diploid AML by NPM1 Status Wt = wild type; mut = mutation. Becker et al, 2010. Overall Survival of Older AML Patients With or Without a FLT3/ITD Mutation Patients enrolled on UK MRC AML16 trial Treated with intensive induction Lazenby et al, 2014. Nonmyeloablative Allogeneic Transplant in Patients by Decade Median follow-up, 2.1 years PFS = progression-free survival; OS = overall survival. Kasamon et al, 2013. Delaying Treatment Safe for Older Patients Sekeres et al, 2009. More Conclusions Performance status and karyotype have a major impact on the likelihood of surviving induction therapy in older AML patients Adverse karyotypes are more common in older AML patients Molecular and cytogenetic features influence outcomes in older AML patients the same way they do in younger AML patients If possible, treatment of an older AML patient should be delayed until an initial risk stratification can be performed Novel Agents in Clinical Development Selected Novel Agents in Clinical Trials for Older Patients With AML Class Examples Purine analog Clofarabinea DNA methylation inhibitor Azacitidine, decitabinea Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor Vorinostatb, pracinostatb Anti-CD33 antibody conjugate Gemtuzumab ozogamicina,b Immunomodulatory agent Lenalidomidea FLT3 kinase inhibitor Quizartinibb, PLX3397b, ASP2215b Polo-like kinase (PLK1) inhibitor Volasertibb Novel cytotoxics CPX-351b aOff-label. bInvestigational. Slide adapted from Ravandi F, 2012. Clofarabine NH2 N N HO Rationally designed purine analog Resistant to deamination and phosphorolysis Inhibition of DNA synthesis and repair Inhibitor of RNR and DNA polymerase Induction of apoptosis N N Cl O F HO RNR = ribonucleotide reductase. Montgomery et al, 1992. Clofarabine Frontline Monotherapy in Elderly AML Patients Parameter N CR (%) OR (%) DOR Age 70 69 33 39 15 AHD 41 39 51 Intermediate CG 46 48 54 Unfavorable CG 62 32 42 OR = overall response; DOR = duration of response; AHD = antecedent hematologic disorder; CG = cytogenetics. Kantarjian et al, 2010. 8.6+ 15 9.5 OS 7.2 12 12 7.2 Clofarabine for Newly-Diagnosed Older AML Patients Median age: 74 years Clofarabine 20 mg/ m2 for 5 days vs. low-dose Ara-C CR rate: – Clofarabine: 22% – Low-dose Ara-C: 12% Burnett et al, 2013. Epigenetic Therapy DNA Methylation Histone Modification Phosphorylation MMMM Methylation Acetylation Azacitidine Decitabine Pracinostat Vorinostat Frontline Decitabine in Older Patients With AML N CR (%) 55 24 18 28 9 20 28 25 <1000 41 29 1,000 to 10,000 11 9 3 0 All Patients Presenting Bone Marrow Blast (%) <30 30 to <50 ≥50 Presenting PBC >10,000 PBC = absolute peripheral blood count. Cashen et al, 2010. Ten-Day Schedule of Decitabine for Older Patients With Untreated AML Percent Response CR Incomplete CR 100 80 60 40 20 0 All Patients Age <74 (N = 53) (N = 25) Blum et al, 2010. Age 74+ (N = 28) Normal Complex Monosomy Karyotype Karyotype 7 / del(7q) (N = 21) (N = 16) (N = 11) Decitabine vs. Treatment Choice TC = treatment choice (best supportive care or low-dose cytarabine). Kantarjian et al, 2012. E2906 Trial on Clofarabine Newly-diagnosed AML, age >60 Multicenter, cooperative group study “7 + 3”/HiDAC Newlydiagnosed AML Randomize HLA-matched sibling? Complete response? Allogeneic transplant Follow Randomize Clofarabine Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), 2012. Decitabine maintenance Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin Castaigne et al, 2012. Lenalidomide Risk Group (ELN) CR (%) CRi (%) PR (%) RD (%) ED (%) Favorable 14 14 14 57 0 Intermediate-1 25 0 17 50 8 Intermediate-2 17 8 8 42 25 Adverse 18 18 9 27 27 • First-line azacitidine then lenalidomide • ORR 40%, including 28% CR/CRi • Common adverse events were gastrointestinal, fatigue, and myelosuppression ELN = European Leukemia Net; ORR = overall response rate; RD = resistant disease; ED = early death. Pollyea et al, 2013. Patients achieving positive outcomes (%) Quizartinib Induces a High Response Rate in Older Patients With Relapsed/Refractory FLT3/ITD AML 100 80 7% 60 40 51% 20 CRc = CR + CRi + CRp. Cortes et al, 2012. 21% FLT3/ITD N=110 CR/CRp CRi 16 of 110 (15%) patients PR remained alive for >12 months after taking CRc 58% quizartinib and were classified as long-term survivors Frontline Volasertib + LDAC vs. LDAC in Elderly Patients Event-Free Survival Maertens et al, 2012. CPX-351: Liposomal Daunorubicin and Cytarabine Parameter CPX-351 (n=26) “7 + 3” Regimen (n=15) 12 (80.0) Pts with 2 risk factors (%) 23 (88.5) Pts with 3 risk factors (%) 3 (11.5) 3 (20.0) CR (%) 11 (42.3) 4 (26.7) CRi (%) 7 (26.9) 0 18 (69.2) 4 (26.7) 60-d mortality (%) 1 (3.8) 6 (40.0) Median EFS (mos) 9.1 1.1 CR + CRi (%) Median OS (mos) Lancet et al, 2012. 23 (88.5) 12 (80.0) Case Study 1: Transplantation Case Study 1 A 67-year-old woman presents with low-grade fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leucopenia Has no comorbid conditions or antecedent hematologic disorder; organ functions are normal Bone marrow exam reveals AML and cytogenetic analysis reveals loss of a translocation between chromosome 9 and 11 at band q23 in 17 out of 20 metaphases What is the recommended therapy for this patient? Case Study 1 (cont.) She receives induction with cytarabine, daunorubicin, and etoposide Achieves a CR • • Remission marrow shows normal karyotype Reduced performance status, ineligible for further therapy until Day 70 Undergoes a nonmyeloablative allogeneic transplant with her HLA-matched sister as donor She is in ongoing remission 1 year after her diagnosis • Normal performance status Case Study 2: Favorable Risk Case Study 2 A 72-year-old man presents in December 2010 with dyspnea and a white count of 149,000 No comorbid conditions or history of an antecedent hematologic disorder Diagnosis: AML Normal karyotype; NPM1c What treatment would you recommend? Case Study 2 (cont.) Receives induction therapy with cytarabine and idarubicin (“7 + 3”) Achieves a CR Started on HiDAC consolidation therapy Relapses after 22 months Re-induced with HiDAC and achieves a second remission Enrolled in a clinical trial for maintenance antiinterleukin-3 receptor (CD123) antibody Remission is ongoing Case Study 3: Progression of AML Case Study 3 A 71-year-old man presents with fever, profound fatigue, anemia, and circulating blasts • ECOG PS of 3 • Bone marrow biopsy, 30% blasts • Complex cytogenetics, including loss of chromosomes 5 and 7 Other past medical history: • Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia for 1 year • Emphysema • Chronic atrial fibrillation/flutter; on anticoagulation therapy • Stage III rectal colorectal adenocarcinoma, neoadjuvant radiation therapy, post-operation chemo 3 years prior What treatment would you recommend? Case Study 3 (cont.) 5-azacitidine 75 mg/m2 for 5 days per cycle; gets monthly treatment as outpatient Peripheral blood cleared of blasts PS improves Bone marrow shows persistent blasts after 6 cycles Disease progression nearly a year later • ECOG PS still 1 Referred for a clinical trial Case Study 4: Other AML subtypes Case Study 4 A 75-year-old woman presents in February 2010 with bruising and petechiae Reports some bleeding when brushing her teeth WBC is 9.3 with 71% promyelocytes, Plt 12, and Hgb 8.4 Bone marrow exam is consistent with APL. You send a specimen for cytogenetic and molecular studies What treatment would you recommend? WBC = white blood cell count; Plt = platelet count; Hgb = hemoglobin count. Case Study 4 (cont.) Receives ATRA/daunorubicin and achieves CR Consolidation with arsenic and ATRA Currently in ongoing remission Key Takeaways Older patients can benefit from treatment in addition to supportive care Risk stratification prior to induction is particularly important for older AML patients Older AML patients are more likely to have unfavorable karyotypes Cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities influence the outcome in older AML patients the same way they do in younger AML patients Patients should be treated in clinical trials whenever possible Novel agents, as well as novel combinations of established agents, are currently under investigation References Appelbaum FR, Gundacker H, Head DR, et al (2006). Age and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood, 107(9):3481-3485. Becker H, Marcucci G, Maharry K, et al (2010). Favorable prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in older patients with cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia and associated gene- and microRNA-expression signatures: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol, 28(4):596-604. Blum W, Garzon R, Klisovic RB, et al (2010). Clinical response and miR-29b predictive significance in older AML patients treated with a 10-d schedule of decitabine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 107(16):7473-7478. Burnett AK (2012). Treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: are we making progress? ASH Education Book, 1:1-6. Burnett AK, Milligan D, Prentice AG, et al (2007). A comparison of low-dose cytarabine and hydroxyurea with or without all-trans retinoic acid for acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome in patients not considered fit for intensive treatment. Cancer, 109(6):1114-1124. Burnett AK, Russell NH, Hunter AE, et al (2013). Clofarabine doubles the response rate in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia but does not improve survival. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 122(8):1384-1394. Cashen AF, Schiller GJ, O’Donnell MR, DiPersio JF (2010). Multicenter, phase II study of decitabine for the first-line treatment of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol, 28(4):556-661. Castaigne S, Pautas C, Terré C, et al (2012). Effect of gemtuzumab ozogamicin on survival of adult patients with de-novo acute myeloid leukaemia (ALFA-0701): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet, 379(9825):1508-1516. Cortes JE, Kantarjian H, Foran JM, et al (2013). Phase I study of quizartinin administered daily to patients with relapsed or refractory acute myleloid leukemia irrespective of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3-internal tandem duplication status. J Clin Oncol, 3(29):3681-3687. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2013.48/8783. Cortes JE, Perl AE, Dombret H, et al (2012). Final results of a phase 2 open-label, monotherapy efficacy and safety study of quizartinib (AC220) in patients 60 yrs of age with FLT3 ITD positive or negative relapsed/refractory acute myeloid Leukemia. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 120. Abstract 48. Dohner K, Schlenk RF, Habdank M, et al (2005). Mutant nucleophosmin (NPM1) predicts favorable prognosis in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: interaction with other gene mutations. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 106(12):3740-3746. European Cooperative Oncology Group (2012). Clorafabine or daunorubicin hydrochloride and cytarabine followed by decitabine or observation in treating older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Accessed on April 18, 2014. Available at: clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01041703 Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellström-Lindberg E, et al (2010). Azacitidine prolongs overall survival compared with conventional care regimens in elderly patients with low bone marrow blast count acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol, 28(4):562-569. References (cont.) Grimwade D, Walker H, Harrison G, et al (2001). The predictive value of hierarchical cytogenetic classification in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML): analysis of 1065 patients entered into the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML11 trial. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstract), 98(5):1312-1320. Harris DJ, Eilers J, Harriman A, Cashavelly BJ, Maxwell C (2008). Putting evidence into practice: Evidence-based interventions for the management of oral mucositis. Clin J Onc Nurs, 12(1):141-152. Higa GM, Gockerman JP, Hunt AL, et al (1991). The use of prophylactic eye drops during high-dose cytosine arabinoside. Cancer, 68(8):1691-1693. Jabbour EJ, Estey E, Kantarjian HM (2006). Adult acute myeloid leukemia. Mayo Clinic Proc, 81:247–260. Juliusson G (2011). Older patients with acute myeloid leukemia benefit from intensive chemotherapy: an update from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk, 11(Suppl 1):S54-S59. Juliusson G, Antunovic P, Derolf A, et al (2009). Age and acute myeloid leukemia: real world data on decision to treat and outcomes from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 113(18):4179-4187. Juliusson G, Billström R, Gruber A, et al (2006). Attitude towards remission induction for elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia influences survival. Leukemia, 20(1):42-47. Kantarjian HM, Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, et al (2012). Multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial of decitabine versus patient choice, with physician advice, of either supportive care or low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol, 30(21):2670-2677. Kantarjian HM, Erba HP, Claxton D, et al (2010). Phase II study of clofarabine monotherapy in previously untreated older adults with acute myeloid leukemia and unfavorable prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol, 28(4):549-555. Kantarjian H, O'Brien S (2010). Questions regarding frontline therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer, 116(21):4896-4901. Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Cortes J, et al (2006). Results of intensive chemotherapy in 998 patients age 65 yrs or older with acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: predictive prognostic models for outcome. Cancer, 106(5):10901098. Kasamon YL, Prince G, Bolaños-Meade J, et al (2013). Encouraging outcomes in older patients (pts) following nonmyeloablative (NMA) haploidentical blood or marrow transplantation (haploBMT) with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide (PT/Cy). Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 122. Abstract 158. Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Frew ME, et al (2001). The presence of FLT3 internal tandem duplication in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) adds important prognostic information to cytogenetic risk group and response to the first cycle of chemotherapy: analysis of 854 patients from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML 10 and 12 trials. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 98(6):1752-1759. References (cont.) Lancet JE, Cortes JE, Kovacsovics T, et al (2012). CPX-351 is effective in newly diagnosed older patients with AML and with multiple risk factors. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 120. Abstract 3626. Lazenby M, Gilkes AF, Marrin C, et al (2014). The prognostic relevance of flt3 and npm1 mutations on older patients treated intensively or non-intensively: a study of 1312 patients in the UK NCRI AML16 trial. Leukemia, (Epub). Löwenberg B, Ossenkoppele GJ, van Putten W, et al (2009). High-dose daunorubicin in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med, 361(13):1235-1248. Löwenberg B, Zittoun R, Kerkhofs H, et al (1989). On the value of intensive remission-induction chemotherapy in elderly patients of 65+ yrs with acute myeloid leukemia: a randomized phase III study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Leukemia Group. J Clin Oncol, 7(9):1268-1274. Maertens J, Lübbert M, Fiedler W, et al (2012). Phase I/II study of volasertib (BI 6727), an intravenous polo-like kinase (PLK) inhibitor, in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML): results from the randomized phase II part for volasertib in combination with low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) versus LDAC monotherapy in patients with previously untreated AML ineligible for intensive treatment. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 120. Abstract 411. Menzin J, Boulanger L, Karsten V, et al (2006). Effects of initial treatment on survival among elderly AML patients: Findings from the SEER-Medicare database. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 108(Suppl). Abstract 1973. Menzin J, Lang K, Earle CC, et al (2002). The outcomes and costs of acute myeloid leukemia among the elderly. Arch Intern Med, 162(14):1597-1603. Montgomery JA, Shortnacy-Fowler AT, Clayton SD, et al (1992). Synthesis and biologic activity of 2'-fluoro-2-halo derivatives of 9beta-D-arabinofuranosyladenine. J Med Chem, 35(2):397-401. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2013). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Acute myeloid leukemia. Version 2.2013. Accessed on April 27, 2014. Available at http://www.nccn.org Paschka P, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, et al (2006). Adverse prognostic significance of KIT mutations in adult acute myeloid leukemia with inv(16) and t(8;21): a Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. J Clin Oncol, 24(24):3904-3911. Pollyea DA, Zehnder J, Coutre S, et al (2013). Sequential azacitidine plus lenalidomide combination for elderly patients with untreated acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica, 98(4):591-596. References (cont.) Rogers BB (2010). Advances in the management of acute myeloid leukemia in older adult patients. Oncol Nurs Forum, 37(3):E168-E179. Sekeres MA, Elson P, Kalaycio ME, et al (2009). Time from diagnosis to treatment initiation predicts survival in younger, but not older, acute myeloid leukemia patients. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 113(1):28-36. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2013). Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: Cancer J Clinicians, 63:11-20. Slovak K, Kopecky J, Cassileth, PA, et al (2000). Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 96(13): 4075-4083. Taskesen E, Bullinger L, Corbacioglu A et al. (2011). Prognostic impact, concurrent genetic mutations, and gene expression features of AML with CEBPA mutations in a cohort of 1182 cytogenetically normal AML patients: further evidence for CEBPA double mutant AML as a distinctive disease entity. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), 117(8):2469-2475. DOI:10.1182/blood-2010-09-307280. Thépot S, Itzykson R, Seegers V, et al (2009). Azacytidine (AZA) as first line therapy in AML: results of the French ATU Program. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts). Abstract 843. Tilly H, Castaigne S, Bordessoule D, et al (1990). Low-dose cytarabine versus intensive chemotherapy in the treatment of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia in the elderly. J Clin Oncol, 8(2):272-279.