Art of Rhetoric - East Penn School District

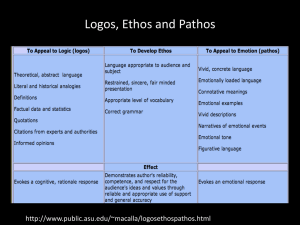

advertisement

Rhetoric—The Art of Persuasion This is Aristotle. He was an ancient Greek philosopher who lived from 384-322 BCE. He was interested in and studied EVERYTHING, including physics, poetry, theater, music, politics, and biology. (He was a pretty smart guy). One of the things he is known for is his study of rhetoric. Rhetoric is the art of making a persuasive argument. (Have you ever heard of a rhetorical question? It’s when someone asks a question, but they don’t want you to actually answer—they are just making a point.) For Aristotle, rhetoric was the art that trumped, or overruled, all the other arts and sciences known in his day. Why? Well, for instance, even if science tells us that all spiders have eight legs, that fact doesn’t matter if there is someone who is so persuasive, he is able to go around convincing everyone that they have 7, or 9, or 24! If people truly believe that spiders have 9 legs, then they are going to act as if that is the “truth,” and refuse to accept any evidence that says something different. They will write stories where spiders have 9 legs, and paint nine legs on spiders in artwork, and pretty soon, even people who are like, “wait a second, I counted the legs on a spider yesterday, and there were only 8,” those people will think they are the ones who are mistaken, because everyone else is telling them otherwise! In other words, rhetoric is the art of bending the world in the direction you want it to go, by winning over the hearts and minds of other people, all through the power of your words. Gifted rhetors (people who practice rhetoric) can have awesome or terrible effects on society, based on how they choose to use their power. One thing is certain: people who are not familiar with how rhetoric works are much more easily persuaded by flawed or unethical arguments. Study this stuff carefully so you aren’t one of them! According to Aristotle, there are three main parts of rhetoric. All of them work together to persuade the audience that the speaker is making a sound argument. (Rhetoric applies to writing as well, but we will discuss it in terms of public speaking here, to make things easier.) The three parts are ethos, pathos, and logos—you may hear them referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle, or the Three Appeals. Ethos is the Greek word for “character,” as in what kind of person you are. The word “ethical” comes from this same root, because ethical things are what a good person would do. In terms of rhetoric, ethos refers to the credibility or believability of the speaker. There are many things that go into establishing the ethos of the speaker, such as: how trustworthy and reliable she is known to be by the audience, whether she is fair or biased, whether she has something personal to gain, whether she is an expert on what is being discussed, and the manner she uses to present her arguments. Sometimes, the audience may make assumptions about the speaker’s ethos that are incorrect. The speaker should try to anticipate these and clear them up at the beginning of the speech. For instance, if someone named John Fitzpatrick Cunningham, Jr. is giving a talk about being a Latino student at a mostly white high school, the audience may question his ethos, simply because his name doesn’t sound Latino. He may want to start the speech by talking about how his father’s family is British, but his mother’s is from the Dominican Republic. It is important to understand things from the audience’s point of view, so that the rhetorician can create a message that will get rid of any doubts they might have. Pathos is the next part of the Rhetorical Triangle. It comes from the Greek word for “suffering” and “experience”--the English words “pathetic” and “sympathy” come from the same root. Pathos is an appeal to the emotions. It is an attempt to get the audience to feel a certain way about the topic at hand, and then act based on those feelings. It also tries to get the audience to put themselves in the shoes of the speaker, to feel things the way she does. Pathos can appeal to both positive emotions and negative emotions. A skilled rhetorician might flip between appeals to different emotions during the course of a single speech. He might also take into account the emotions the audience is already feeling before he speaks--either because of an event or occasion that is taking place or pre-existing feelings they have on the topic. Logos completes the Triangle. Logos is an appeal to logic or reason. Any fact or statistics the speaker has found through research would fall under the category of logos. She might also quote an expert on the topic or use other evidence to help her argument. Some might think that logos is the only tool a speaker needs to convince the audience of her position. If human being were totally logical creatures, like robots, that might be true--however; we all know there are times when people are less than rational. They might be biased against the speaker, or have strong emotions on the topic that make them unlikely to listen to reason. They might also just be hungry, or tired, and unable to concentrate on a logical argument. A good rhetorician takes this all into account and uses all three parts of the Rhetorical Triangle to make the most convincing argument possible. Now, even if a speaker uses ethos, pathos, and logos to the best of her ability, there is no guarantee she is going to convince every person in her audience to go along with what she says. However, what she can make sure of is that she won’t be dismissed right away as untrustworthy or ignorant (lack of ethos), as being emotionally insensitive (lack of pathos), or as illogical (lack of logos). The audience will have to take what she is saying seriously, even if they don’t end up agreeing with her. And that’s enough to make Aristotle proud. Terms to Know Rhetoric Rhetorical Device Aristotle Rhetorical Triangle Appeal Hyperbole Understatement Parallel Construction Rhetorical Question