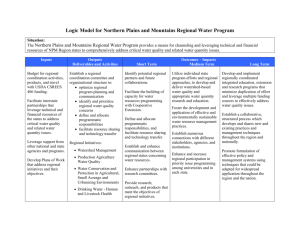

Rest of world - Centre for Economic Policy Research

advertisement

“Global liquidity and drivers of cross-border bank flows” by Cerutti, Claessens & Ratnovski Comments by Robert McCauley*, Senior Adviser Monetary and Economic Department For The Tenth Annual Workshop on Macroeconomics of Global Interdependence, organised by the Centre for Economic Policy Research, Central Bank of Ireland and Trinity College Dublin Dublin, 6-7 March 2015 * Views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily the views of the BIS What this paper does Analyses 77 countries over the period 1990-2012. LHS: BIS locational banking statistics (Table 6): Allowing a long time series. Adjusting for foreign exchange valuation effects. Including bank security holdings. Suggestions: - Make more clear the construction of LHS variable - Allow a Q4 seasonal, especially for interbank flows. - Discuss different behaviour of interbank and nonbank. - Re-run benchmark regression w/o financial centres. RHS: Global liquidity drivers: VIX, TED spread, bank leverage, real credit growth, yield curve slope yield curve, real policy rate, M2 growth. A particular contribution: non-US drivers for global liquidity. 2 What this paper finds: familiar results VIX, US broker-dealer leverage and term spread matter. Results for full sample driven by latter subsample, 2001-2012. 2001-06 similar to 2001-2012. Big effects: VIX 25th => 75th percentile => 5+%, 3+5 for bank, nonbank Leverage 25th => 75th => 5+%, 4+% 3 What…finds: familiar results (con’d): term spread? Authors cite Bruno & Shin, but JME version of their paper has no term spread. Authors say: “Banks borrow short-term and lend long-term, so their domestic investment opportunities are less profitable when the yield curve is flat: this may trigger banks’ search for yield, including in the form of cross-border loans”. This implies substitution of cross-border and domestic credit while domestic credit and M2 results point to complementarity. Versus work by Estrella (with Hardouvelis (1991) and Mishkin (1998)) that uses flat or inverted yield curve to predict recession (ie as indicator of tight money)? Mid-2000s as an unusual case of tightening at so “measured” a pace that term premium went down, VIX went down, carry trades enabled? Distinguish term premium from term spread? 4 Term spread and its components Source: Rosenberg and Maurer, “Signal or noise: implications of the term premium for recession Forecasting”, FRBNY Economic Policy Review, July 2008, p 5. 5 What…finds: familiar results (con’d): interest rate gap? Authors find no effect of yield gap (or even negative for reduced advanced and large emerging market sample) vs Bruno & Shin in REStud. Could point to a problem with proxies for local credit demand, namely GDP growth and inflation. Re-run yield gap without local inflation? Use local credit growth instead of proxies? (Positive coefficient on real federal funds rate could also result from its proxying for global economic activity.) Some have synthesised local risk-free rates by subtracting sovereign CDS spread from local yields. 6 What this paper finds: European bank leverage matters Leverage of broad banking sector for UK and euro area from flow of funds entered separately from leverage of US brokerdealers. While multicollinearity prevents a head-to-head comparison, bank leverage in UK and euro area works as well as US brokerdealer leverage for non-G4 sample. Authors go too far: “UK ban leverage has a higher explanatory power than US bank leverage”: - US: coefficient of .364, R2 of 0.035 - UK: coefficient of .930, R2 of 0.031, but lower variance! And UK bank leverage works as well for Asia and Western Hemisphere as US broker dealer leverage. Interesting result because US broker-dealer leverage based on repos, whereas UK and euro area bank leverage measure whole banking system. 7 Bank leverage measures for G4 8 What this paper finds: sterling drivers for global liquidity? Cerutti et al suggest that sterling variables drive growth of cross-border bank claims: Not just UK bank leverage but £ TED UK credit growth £ real policy rate £ M2 growth And £ TED affects cross-border bank lending to Asia and Western Hemisphere. Problem: there is very little sterling cross-border claims. Broader conceptual problem: international finance assuming triple coincidence 9 Foreign currency assets and liabilities of BIS reporting banks Bruno and Shin, Cross-border banking and global liquidity, BIS Working Paper no 458, August 2014, forthcoming Review of Economic Studies, citing Table 5A. 10 Need to free ourselves of triple coincidence? Tend to assume that the triple coincidence: National borders—hence use crossborder stocks. Economic units—UK banks respond to domestic variables. Currency—so sterling yields relevant for UK banks. “for the UK and Euro Area, where an increase in bank deposits (part of M2) translates into larger bank balance sheets and more crossborder lending”. But, but, but 11 Triple coincidence All firms are domestic, All domestic assets and liabilities are denominated in domestic currency, Country coincides with spending units and with currency. Global liquidity flows out of source country to ROW through cross-border credit. Home country Domestic firms Domestic currency Rest of world Foreign firms Foreign currencies 12 But, but, but Some domestic firms are multinationals. Some foreign multinationals present domestically. Part of the domestic banking system dollarised (or euroised) UK and European banks borrow and lend in dollars outside of their home countries. Home country Domestic multinationals Rest of world $ (€) Foreign multinationals 13 Dollar credit to borrowers outside the US, end-2013 Source: McCauley, McGuire and Sushko (2015). 14 What this paper does not do Analyse second phase of global liquidity. At the margin, dollar bonds issued by nonbanks outside the United States have gained on bank loans. Growth of these bonds outstanding responds to term premium, which in turn is focus of unconventional monetary policy (ie large-scale bond buying) of Federal Reserve. 15 Effect of changes in US Treasury term premium on growth of stock of US dollar bonds issued by non-US borrowers 16-quarter rolling regression coefficient and standard errors 16 Fed’s unintended effect: $ bond net issuance 2010-2014 In billions of US dollars 2000 Non-US 1500 US corporate US GSE US ABS 2012 2013 1000 500 0 -500 2009 2010 2011 2014Q3 -1000 -1500 -2000 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Financial Accounts; McCauley, McGuire and Sushko (2015). 17 A big question: Monetary policy divergence?? Federal Reserve expected to raise IOER from 0.25% in 2015 to 2% in 2017. ECB and Bank of Japan to Term premium: US Treasury vs bunds/OATs add $2-3 trillion to their bond holdings. At some stage, Federal Reserve to stop replacing maturing bonds. What happens if major central banks on both sides of globally integrated bond market? 18 Policy divergence: quantities Manoj Pradhan and Sung Woen Kang, “The QE chartbook: The QEquation: ECB + BoJ = Fed?”, Morgan Stanley Global Economics, 20 January, 2015. 19 Conclusions Paper contributes to studies of cross-border banking and global liquidity by suggesting the importance of European bank leverage. Given the tests reported, skeptics could take the view that US broker-dealer leverage is sufficient, but it is nevertheless remarkable that general European bank leverage does so well. More thought could be given to interpretation of term spread, possibly using distinction between expectational component and term premium. Findings regarding role of sterling variables problematic, suggest need to free analysis from assumption of triple coincidence. Beyond paper lies question of divergent central bank unconventional policies and effects on flow of global liquidity through bond markets. 20