FOD 3160 Regional Cusine Hawaii

advertisement

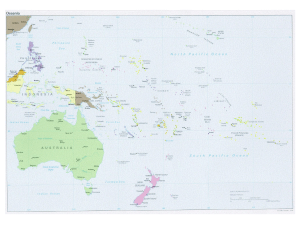

Identify and explain what makes the cuisines of the region unique; e.g., climate, fuels available, trade, economic conditions, common use of major foodstuffs • • • • Temperatures range from highs of 85–90 °F (29–32 °C) during the summer months to 79–83 °F (26– 28 °C) during the winter months. Rarely does the temperature rise above 90 °F (32 °C) or drop below 65 °F (18 °C) at lower elevations. Temperatures are lower at higher altitudes; in fact, the three highest mountains of Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa, and Haleakalā often receive snowfall during the winter. There is small annual variation in temperature range. This is because there is only a slight variation in length of night and day from one part of Hawaii to another and because all its islands lie within a narrow latitude band. Water temperatures are mild for hundreds of miles around, the air that reaches Hawaii is neither very hot nor very cold. The other reason for the small variation in air temperature is the nearly constant flow of fresh ocean air across the islands. Just as the temperature of the ocean surface varies comparatively little from season to season, so also does the temperature of air that has moved great distances across the ocean; the air brings with it to the land the mild temperature regime characteristic of the surrounding ocean. In the central North Pacific, the trade winds represent the outflow of air from the great region of high pressure, the North Pacific High, typically located well north and east of the Hawaiian Islands. The Pacific High, and with it the trade-wind zone, moves north and south with changing angle of the sun, so that it reaches its northernmost position in the summer. This brings trade winds during the period of May through September, when they are prevalent 80 to 95 percent of the time. From October through April, the heart of the trade winds moves south of Hawaii; however, the winds still blow much of the time. They provide a system of natural year-long ventilation throughout the islands and bring mild temperatures characteristic of air that has moved great distances across tropical waters. • TRADE • EXPORTS http://www.census.gov/foreigntrade/statistics/state/data/hi.html • IMPORTS • http://www.census.gov/foreigntrade/statistics/state/data/imports/hi.html • ECONOMIC CONDITIONS • http://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/annuals/2013/2013-12-currenteconomic-conditions.pdf • COMMON USE OF MAJOR FOOD STUFF • http://www.to-hawaii.com/food.php Identify and explain the effect of wars, redrawn borders and ethnic migration on the region’s cuisine • • http://www.greenchipstocks.com/articles/climate-change-hawaii/602 http://brittanytodd.hubpages.com/hub/Hawaiian-Food-Culture-The-Evolution-and-Effects-of-LocalFood • 1.5 describe changes in foods, food patterns and food preparation techniques as people adapt to new cultures, considering: 1.5.1 accessibility of traditional and nontraditional foods 1.5.2 access to and understanding of nutrition information 1.5.3 the role of food in retaining cultural heritage 1.5.4 the role of food in adapting to a new cultural environment • • • • • • evaluate the physical, psychological and social impact of evolving food patterns as individuals and families adapt to an adopted culture • • • • • • • 1.7 describe food sensibilities (aesthetics), considering: 1.7.1 food planning principles 1.7.2 seasonings 1.7.3 characteristic food and flavour combinations 1.8 analyze how nutritional needs are met through the food patterns of the region Discuss the significance of religion in the cuisines of the region • Hawaiian religion is polytheistic, with four deities most prominent: Kāne, Kū, Lono and Kanaloa. Other notable deities include Laka, Kihawahine, Haumea, Papahānaumoku, and, most famously, Pele. In addition, each family is considered to have one or more family guardians known as ʻaumakua. • One breakdown of the Hawaiian pantheon[3] consists of the following groups: • the four gods (ka hā'n') – Kū, Kāne, Lono, Kanaloa • the forty male gods or aspects of Kāne (ke kanahā) • the four Hundred gods and goddesses (ka lau) • the great Multitude of gods and goddesses (ke kini akua) • the spirits (na ʻunihipili) • the guardians (na ʻaumākua) • Another breakdown[4] consists of three major groups: • the four gods, or akua: Kū, Kāne, Lono, Kanaloa • many lesser gods, or kupua, each associated with certain professions • family gods, ʻaumakua, associated with particular families • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Kahuna and Kapu The kahuna were well respected, educated individuals that made up a social hierarchy class that served the King and the Courtiers and assisted the Maka'ainana (Common People). Selected to serve many practical and governmental purposes, Kahuna often were healers, navigators, builders, prophets/temple work, and philosophers. They also talked with the spirits. Kapu refers to a system of taboos designed to separate the spiritually pure from the potentially unclean. Thought to have arrived with Pāʻao, a priest or chief from Tahiti who arrived in Hawaiʻi sometime around 1200 AD,[8] the kapu imposed a series of restrictions on daily life. Prohibitions included: The separation of men and women during mealtimes (a restriction known as ʻaikapu) Restrictions on the gathering and preparation of food Women separated from the community during their menses Restrictions on looking at, touching, or being in close proximity with chiefs and individuals of known spiritual power Restrictions on overfishing Hawaiian tradition shows that ʻAikapu was an idea led by the kahuna in order for Wākea, the sky father, to get alone with his daughter, Hoʻohokukalani without his wahine, or wife, Papa, the earth mother, noticing. The spiritually pure or laʻa, meaning "sacred" and unclean or haumia were to be separated. ʻAikapu included: The use of a different ovens to cook the food of male and female Different eating places Woman were forbidden to eat pig, coconut, banana, and certain red foods because of their male symbolism. [9][10] Punishments for breaking the kapu could include death, although if one could escape to a puʻuhonua, a city of refuge, one could be saved.[14] Kāhuna nui mandated long periods when the entire village must have absolute silence. No baby could cry, dog howl, or rooster crow, on pain of death. Human sacrifice was not uncommon The kapu system remained in place until 1819. • Prayer was an essential part of Hawaiian life, employed when building a house, making a canoe, and giving lomilomi massage. Hawaiians addressed prayers to various gods depending on the situation. When healers picked herbs for medicine, they usually prayed to Kū and Hina, male and female, right and left, upright and supine. The people worshiped Lono during Makahiki season and Kū during times of war.[citation needed] • Heiau, served as focal points for prayer in Hawaiʻi. Offerings, sacrifices, and prayers were offered at these temples, the thousands of koʻa (shrines), a multitude of wahi pana (sacred places), and at small kuahu (altars) in individual homes. • Missionaries arrived in 1820, and most of the aliʻi converted to Christianity, including Kaʻahumanu and Keōpūolani, but it took 11 years for Kaʻahumanu to proclaim laws against ancient religious practices. • In the aftermath, there were some who still practiced their old beliefs, and some who practiced a Christian version of the old traditions.