Cyber Security DA - Millennial Speech & Debate

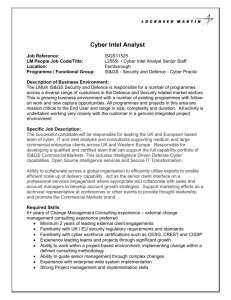

advertisement