Six Sigma Implementation in a Small Organization

advertisement

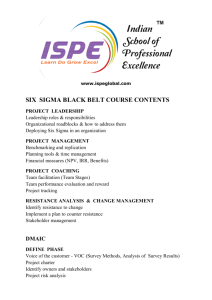

Six Sigma Implementation in a Small Organization Forrest Elton Hett 2339 N. Richmond Wichita, Ks 67204 316-706-5976 motorhett@gmail.com B.B.A. In Entrepreneurship from Wichita State University Currently a Graduate Student in Industrial Engineering at Wichita State University APICS Kansas Student Chapter S272 Full-Time Graduate Six Sigma Implementation in a Small Organization Abstract Six Sigma is a successful strategy to increase organizational effectiveness. The Six Sigma framework can be applied to small businesses even though they do not have the resources a large company may have for implementation. Struggles and solutions regarding Six Sigma faced by small organizations are outlined in this paper. 1 Six Sigma was first implemented by Motorola in the mid 1980’s and was a scientific approach to measure and reduce the defects of a process through calculated experimentation. Implementation in a small organization can be effective with the correct management and structure. Many large firms have implemented Six Sigma practices effectively and are now expecting this performance from smaller suppliers (5, pg. 1). Large organizations have implemented Six Sigma with great results but smaller organizations need to reap similar benefits without investing millions of dollars. This paper will give an introduction to the methodology behind implementing Six Sigma in a small organization. Definition and Common Implementations of Six Sigma The motivation behind Six Sigma is to reduce the cost that arises from poor quality. Quality related costs have been measured to be as much as 40% of sales in some organizations (1, pg. 48). These costs, known as the Costs of Poor Quality (COPQ), can occur in many different ways ranging from scrapping of work in process, customer returns after the products are sold and even retyping letters (1, pg. 49). Much of the blame for poor quality can be placed in the processes used to get to the final product. Six Sigma methodology is a way to work through the processes and ask the correct questions in order to create a process that has less opportunity for variation and failure. The basic foundation of Six Sigma is a relatively simple strategy to understand where defects can occur and develop a new process that will improve over the existing process. This procedure is structured as an experiment that will guide the organization by the results, and decisions will be made from this vital information. The information gained will help managers control process variation (2, pg. 16). 2 The Six Sigma process is done, along with other aspects, through a framework designed mainly by Motorola, known as the DMAIC framework (5, pg. 5). The DMAIC framework first entails defining the initiative. This may involve things such as defining customer requirements, key processes of variation and end results (1, pg. 18). Secondly, the defects must be defined and measured. This will allow the company to see where the problems exist and the impact Six Sigma made. The third step is to analyze the current situation. Analysis starts with getting the information in a useable format and then proceeding to interpret and hypothesize what is actually affecting the results. The fourth step is to improve on the current process. This is the step in which planning and brainstorming occur in order to obtain input from all stakeholders involved in the process and gain all the information possible to make the process function better. The last stage is the control stage which involves implementation of systems to make sure the changes are continually applied and the processes do not slip back to the way they were before the Six Sigma application (4, pg. 18). Six Sigma incorporates measurements that demonstrate the importance of what is Critical to Quality (CTQ) and what is driving the variation in the system. If an organization can measure what the customer wants, and what drives the possibility of failure within that goal, then the organization can effectively change processes in order to more successfully satisfy customer needs. The implementation of Six Sigma in a large organization requires a significant time and financial investment. Burton and Sams (2, pg. 37) outline a common training sequence in their book. First, executive training will take place over four to eight weeks and will be considered the champion level. The executives are trained at this level in order to develop and support a Six Sigma culture. Second, the individuals that will become the experts in the organization will 3 receive black belt training that will last five months, including a training project. Next, the more basic green belt training will begin, lasting 5 days followed by a mandatory project. After that, the most basic yellow belt training will occur for individuals who will use Six Sigma techniques for limited everyday use. All the training can commonly be done in a year, but it commonly takes two to three years for a large company to effectively incorporate the methodologies and practices. Difficulties in Small Organizations Small organizations have a special set of difficulties when implementing a Six Sigma methodology that makes the implementation process different than that of a large organization. There are two types of variation in an organization. One is common cause variation and the other is special cause variation. The difficulty with these two types of variation is they are dealt with differently (1, pg. 59). A small organization will have processes that are probably not as well defined and are not repeated as often as in a large organization. The small organization will not as easily identify the difference between a problem with the system (common cause variation), or one time problem that needs to be rectified and will then not arise again (special cause variation). The special cause variation needs to be dealt with at that moment and then move on. The common cause variation needs to be researched, and a new process needs to be developed to address the issues that are entailed with the problem. Also, since a small organization will not repeat the same process as many times as a large organization, it will take longer to reach a statistically significant sampling of data to prove the solution satisfied the problem. According to Patel (5, pg. 12), the limited resources of a small or medium size organization can pose difficulties for the implementation of Six Sigma such as employee 4 education, flow of information and practical experimentation. These are all things that are much more limited in a smaller organization. The large implementations of Six Sigma require many employees undergoing full time training and focusing on Six Sigma and their related projects. This may be a completely impossible investment for a small or medium sized organization to undertake. The common training and implementation process may take years to show a return (2, pg. 36). Small and Medium sized organizations may not even be able to investigate an investment of that magnitude. A common implementation of Six Sigma may have at least several full time employees working for the initiative within an organization (5, pg. 19). Without a full time dedication, an incorrect implementation of this may lead to poor acceptance of the movement within the company. This will not allow the process to fully develop or may delay the cost savings. Small organizations are more likely to fall prey to this than a large organization that can have dedicated managers who will dedicate all their time to making sure the employees understand and embrace the methodologies and apply them correctly. The size of the organization and availability of financial resources always dictate the implementation strategy (5, pg. 19) but without the ability to dedicate even one employee full time may lead to a disaster of the project. Small Organizations Benefit from Six Sigma Even though small organizations have a special set of difficulties when implementing an official Six Sigma strategy, they can also benefit greatly from the program. According to Patel, Six Sigma is more a management program and not a technical program (5, pg. 9). This means that management of a small organization should be able to effectively implement a management philosophy and change the culture of the organization just like a large organization. 5 Thomas and Barton observed the application of Six Sigma principles in a small engineering firm and it showed great success even in the early stages. A 55% reduction in the rejection rate as well as a 12% energy reduction was observed after the experiment. Performance was also increased by 31% in throughput and downtime was reduced from 5% to 2% (6, pg. 125). This shows that in a company with only 150 employees, a very positive result can be obtained. This company only trained one employee to the black belt level and then allowed a small team to work with him to obtain the results. This is just one example of a company increasing output and decreasing costs with a relatively small investment in Six Sigma, translating into significant gains for the company. Because they had a well defined goals for a project, Six Sigma proved successful for them. Implementing a Six Sigma Culture in a Small Organization Since Six Sigma has been defined not as a technical program that must be implemented in a rigid hierarchy but as a methodology that is flexible in many different environments, small organizations are able to train in the practices and benefit when implemented correctly. Even though small organizations do not have the resources that a large organization can use to push through an elaborate Six Sigma structure, there are concepts and tools they can use to have success without causing them to go bankrupt in the process. As stated before, one of the main factors of success is the full acceptance and adoption of the methodology as an everyday practice for managers and employees. According to Patel, one strength of implementing Six Sigma in a small organization is the open communication between employees and managers (5, pg. 81). Since a small organization commonly has fewer levels of management hierarchy, the communication can move very quickly from where it is gathered to the people who can make a change in the process. When 6 choosing a person or persons to use as the Six Sigma pioneer within the company, they must already have good communication and rapport with the other employees as well as being a good and patient teacher. This increases the likelihood of other employees identifying with them, understanding the concepts and successfully applying the principles. This also goes along with Patel’s suggestion that support from top management is crucial to success (5, pg. 12). Top management support allows the Six Sigma implementation to change the culture and bring about a new way of thinking to solve problems. Burton and Sams outline several key principles of implementing Six Sigma in any organization but specifically in a small organization. One of them is linking the vision to only the most critical issues (2, pg. 67-8). The Pareto principle outlines that 80% of the issues can be taken care of with 20% of the fixes. Implementation of Six Sigma should be focused on the issues that will bring about the most solutions. The chosen projects on which to implement the Six Sigma strategy are even more critical in a small organization due to limited resources. It would be easy for any organization to get bogged down attempting to apply Six Sigma to all their projects initially, but care must be taken when choosing projects that will have the best results in the shortest time period. The objectives must be communicated by management to the project coordinators regarding the goals of the implementation in order to select and solve the most critical issues. Patel also touches on this subject by stating that there will be many opportunities, but time and resources will define the scope of projects (5, pg. 82). The common paradigm that surrounds the hierarchy of necessary green, yellow and black belt training can be misleading for small organizations. A successful implementation in a small organization does not require all levels of training. Gnibus and Krull observed in their testing that training to the green belt level yielded excellent results for the organization in their test (3, 7 pg. 51). The training can be costly and time consuming and only training to a green belt level can prove successful without the excessive costs involved with other levels of training. Patel also states that the level of training does not determine the degree of success the organization will have (5, pg. 82). If the organization is willing to adopt the methodologies and work with a limited amount of training, they will be able to successfully apply it to the issues that will arise in the organization even though they have not trained to the extent of much larger organizations. There are two options regarding the training for Six Sigma. An organization can develop an in-house education structure or can hire an outside firm. Breyfogle et al. state that an inhouse training program is probably not the best idea because it can take years to develop the needed resources to have a successful program. If an outside firm is hired they will commonly train a smaller group of people and allow those people to use the training material to train others in the organization (1, pg. 147-8). This process will be a faster and more effective structure due to the experience the trainers have with Six Sigma. It may look more expensive in the beginning, but the cost of employees developing a program that is not effective would cost a great deal more. A small organization will not likely have the resources to develop any kind of effective Six Sigma training and will have the most success by hiring a competent firm to educate a handful of individuals to manage projects within the company. Training can be completed successfully with two different approaches. Thomas et al. showed success in a small organization with only one individual trained to the black belt level (6, pg. 121). Gnibus and Krull observed successful results with a handful of individuals trained to the green belt level (3, pg. 51). These are two different approaches that both yielded success. This shows that the implementation’s success does not depend on the level of the training, but on the ability of individuals to teach, connect, communicate, learn and understand the scope of the 8 education, not only applying it to problems faced but extending it to new types of unforeseen problems. A small organization can be successful at implementing the Six Sigma plan using these principles. Conclusion Six Sigma is not a discipline that can only be used by large organizations. It can be effective in a small organization with the correct understanding of how resources should be used. Competent individuals must be chosen to pilot the project. Clear and precise goals are critical to the success of the Six Sigma implementation. It will require a financial investment, but will also reward the company as long as it is embraced and supported by the management. It has been proven successful in different types of small companies with various styles of education, tools and training. In conclusion, Six Sigma is an approach that can be successfully applied in small organizations in order to realize significant cost savings, increased quality and greater customer satisfaction. References 1. Breyfogle, Forrest III, Cupello, James & Meadows, Becki. “Managing Six Sigma: a practical guide to understanding, assessing, and implementing the strategy that yields bottom line success”, Wiley, New York 2001 2. Burton, Terence & Sams, Jeff. “Six Sigma for Small and Mid-Sized Organizations”, J. Ross Publishing, Inc., Florida, 2005. 3. Gnibus, Robert & Krull, Rik. “Small Companies See the Money”, Quality, Aug 2003; 42, 8. Pg. 48 4. Nelson, Karen. “A Study of Six Sigma Methodology on Defect Reduction in a Wire Bundle Assembly”, Wichita State University, Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering, 2008. 5. Patel, Dharmesh. “Initiation and implementation of six sigma in a small organization”, Wichita State University, Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering 2004 9 6. Thomas, Andrew & Barton, Richard & Chuke-Okafor, Chiamaka. “Applying Lean Six Sigma in a Small Engineering Company – A Model for Change”, Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Vol. 20 No. 1, 2009, p. 113-129. 10