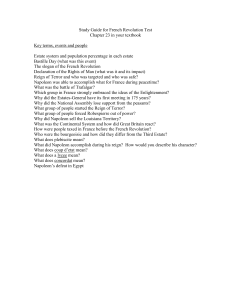

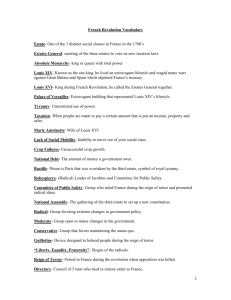

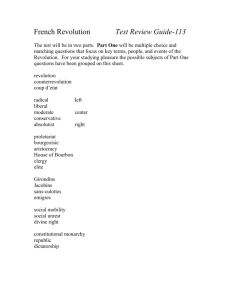

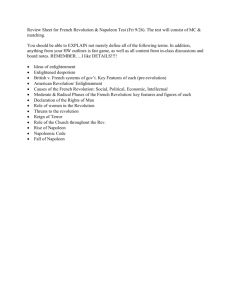

Unit5Plan - Doral Academy Preparatory

advertisement