Greco-Persian Wars Reading

advertisement

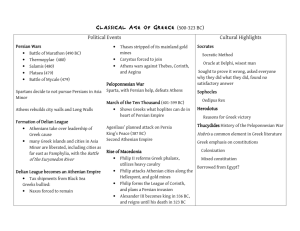

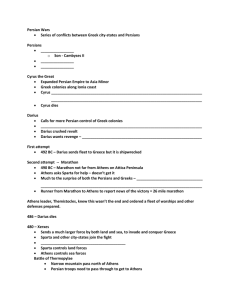

World History Ch. 4: Eurasian Empires The Greco-Persian Wars Ionia and the Ionian rebellion: 545-494 B.C.E. When the Persians annexed Ionia in about 545 B.C.E., acquiring a foothold on the Aegean, the strongest city state in mainland Greece was Sparta. None of the Greek states risked an armed excursion in defense of the Ionians, but the Spartans did send a message to the Persian emperor, Cyrus, warning him to keep away from Greece. His reply, as reported, suggests genuine bewilderment. He asked, “Who are the Spartans?” Far from keeping away, an expedition of 514 B.C.E. approached alarmingly close to Greece from the north, conquering Thrace and Macedonia to bring the northern coast of the Aegean under Persian control. But it was on the coast of Anatolia that the crisis intensified. In 499 B.C.E., the cities of Ionia rebelled against their Persian satrap. They were supported to a limited extent by Athens. The rebellion continued fitfully until finally put down in 493. But this region was now established as an area of friction between Persia and Greece. Geographically Ionia seemed a natural extension of Persia’s great land empire. But culturally the Ionians were linked to all the other Greek-speaking peoples round the Aegean Sea. Athens became the main target of the Persian emperor's hostility, partly because of her support for the Ionian rebels, but also because the tyrant Hippias, expelled from Athens, was at the Persian court offering treacherous encouragement. In 490 B.C.E., Darius launched his attack. A Persian fleet sailed along the southern coast of Anatolia. According to Herodotus, it numbered 600 ships. The horses of the famous Persian cavalry were in transport vessels; the troops were carried in triremes1. From Ionia this armada set a course straight across the Aegean, pausing only at Naxos and other islands to take hostages and press recruits into the army. The destination was Marathon, a plain to the north of Athens on which the cavalry would have room to maneuver. The army landed on the island of Euboea, conquered the small city of Eretria, made the short crossing to the mainland at Marathon, and waited. Marathon: 490 B.C.E. In Athens, the decision was made to send an army to confront the Persians, rather than concentrate on defense of the city. A runner, whom Herodotus names as Pheidippides, was sent to seek help from Sparta. He completed the journey of about 150 miles (240 km) in two days. The Spartans agreed to cooperate. But a religious ceremony prevented them from setting off until the next full moon, which was in six days’ time. At Marathon 10,000 Greek hoplites2 confronted perhaps 25,000 Persians. The Persians waited for the Greeks to attack across the plain, exposing themselves to the cavalry. The Greeks crept forward, night after night, with a ruse to frustrate the Persian horsemen. 1 A fast, agile warship so-named because of the three rows of oars on each side. The heavily-armed Greek infantry soldier. Hoplites take their name from the hoplon, the heavy shield, that they carried. 2 World History Ch. 4: Eurasian Empires They felled trees to create a barricade against the cavalry, and they moved them gradually forward under cover of darkness. The plain was considerably reduced in this way, when word came one night that the Persian cavalry had moved temporarily elsewhere (the reason is unknown). At dawn the Greek hoplites charged in an extended line across the open ground. Their bronze armor and long spears proved too much for the lightly armed Persian infantry. Even so the Persian advantage in numbers meant that the battle was hard fought, making Herodotus' account of the casualties (192 Athenian dead to 6400 Persians) somewhat hard to believe. The Persian survivors were rescued from the beaches by the fleet, which then moved south to threaten Athens. The Athenian army marched rapidly home to defend the city, and the Persians decided against an assault. They withdrew across the Aegean. A day or two after the event, 2000 Spartans arrived. They visited the battlefield as admiring tourists, to inspect the Persian dead. The fallen Athenians were buried beneath a great memorial mound (even today it stands 9 meters high). The survivors were acclaimed as heroes. Aeschylus, the great tragedian, fought that day. He ultimately had much in his life to be proud of, but he said that nothing could compare with being a veteran of Marathon. Themistocles and the Athenian fleet: 490-480 B.C.E. Nobody doubted that the Persians would be back, but the death of Darius in 486 B.C.E. extended the lull before the storm. Three years later a rich new vein of silver was discovered in the mining district of Laureion, which was owned and run by the Athenian state. Themistocles persuaded his fellow citizens to apply their windfall to a collective cause: the building of a navy stronger than any other in Greece. By 480 there were 200 triremes in the Athenian fleet. Thermopylae: 480 B.C.E. A vast Persian force led by Xerxes I, the son of Darius, made its way along the northern coast of the Aegean. The troops were described in mesmerizing detail by Herodotus, writing only half a century later. He listed 1,700,000 soldiers3, including 80,000 cavalry. They were accompanied by a fleet of 1207 triremes, each with 200 men on board. Adding in subsidiary troops, Herodotus arrived at a grand total of 5,283,320 - not including eunuchs and female cooks. These wildly improbable figures suggest the scale of the renewed threat as perceived in Greece. The only difference this time was that such a juggernaut moves slowly. There was time to plan. At a central point of mainland Greece, the Isthmus of Corinth, thirty-one city-states met in the autumn of 481 B.C.E. and again in the spring of 480 to devise a strategy. It was agreed that all 3 In The Histories, Herodotus explained how the Persians determined the exact size of their army: “At Doriscus, Xerxes was occupied in numbering his troops. The grand total, excluding the naval contingent, turned out to be 1,700,000. The counting was done by first packing 10,000 men as close together as they could stand and drawing a circle round them on the ground; they were then dismissed, and a fence, about waist-high, was constructed round the circle; finally other troops were marched into the area thus enclosed, and dismissed in their turn, until the whole army had been counted.” World History Ch. 4: Eurasian Empires would combine their resources, both military and naval, in a common force under the command of Sparta. The immediate question was where to make a stand against the advancing Persians. The chosen site was Thermopylae, a long narrow valley through which any army must pass if moving down the coast towards Athens. Leonidas, one of the two Spartan kings, was in command of the Greek army when the confrontation came. His Spartan contingent was as yet only an advance guard of 300 men. He stationed them under his immediate command at the narrowest part of the pass. The glittering Persian army had at its head the emperor himself, Xerxes, son of Darius. On two successive days he ordered his best troops into the narrow defile. But as at Marathon, ten years earlier, the Persians suffered heavy losses from the longer spears of the Greek hoplites. The situation appeared to be an impasse, almost literally until it was resolved by treachery. In the hope of a large reward a Greek (a certain Ephialtes, named by Herodotus to ensure his eternal infamy) informed Xerxes that a hidden path through oak woods on the nearby hills would bring troops, unseen, to the other side of the pass. A Persian contingent took that route during the night. Before dawn, spies brought Leonidas news of the imminent danger. He ordered the main body of the army to retreat southwards. Then he prepared, with his 300 Spartan hoplites and a few others, to face an onslaught from both ends of the pass. All the Spartans died, selling their lives at a high price – Herodotus wrote that the terrified enemy soldiers had to be whipped by their commanders into confronting these Greeks. Their fate became the enduring monument to Spartan discipline and valor, captured in a famous epitaph inscribed on a column in the pass: “Stranger, go tell the Spartans that we lie here - obedient to their laws.” Now it was the Athenians who were in the front line against the victorious invaders. As the Persian army moved south towards Attica, the debate in Athens was whether to defend the city or make a strategic withdrawal. Salamis: 480 B.C.E. Themistocles, who has already persuaded his fellow citizen to invest in a navy, urged withdrawal. According to a story told by Herodotus, he made good use of the Oracle at Delphi which had told them to put their trust in a “wooden wall.” Themistocles argued that what the oracle clearly had in mind was a ship. His advice was accepted. Athens was evacuated, apart from a few stalwarts who interpreted the “wooden wall” differently; they retreated to the sacred precinct of the acropolis and built around it a wooden palisade. The rest of the inhabitants were taken by ship across the narrow strait separating Athens from the island of Salamis. Reaching Athens, the Persians fired blazing arrows into the wooden barricade. Then, with some difficulty, they assaulted the steep acropolis. After slaughtering those sheltering in the temple, they seized the treasures and demolished the buildings. Athens, so recently given a new grandeur World History Ch. 4: Eurasian Empires in the reign of Pisistratus, was reduced to rubble. But the destruction made possible the rebuilding of Athens4 and an even more glorious city. Meanwhile the Greek fleet was gathered in the narrow stretch of water between Salamis and the mainland. Themistocles persuaded his allies to make a stand there, prevailing over those Peloponnesian states who preferred to abandon Attica and draw the line at the more defensible Isthmus of Corinth. The Greek fleet was smaller than the Persian. It numbered only 380 triremes (of which about half were Athenian), and the Greek ships were slower. Themistocles argued that these disadvantages would be irrelevant in a restricted space, where Greek fighting skills could tip the balance (as in the narrow pass at Thermopylae). His plan depended on the Persian fleet being enticed into the strait at the eastern end of the island of Salamis. Prompted by some deliberately misleading diplomacy, the Persians fell into the trap. As the Greek triremes began to ram and sink them, panic spread among the constricted Persian ships making them ever more vulnerable. The Greek victory was overwhelming. Plataea and Mykale: 479 B.C.E. The Persians still occupied Attica, and the Athenians could not hope to dislodge them without Spartan assistance. This was provided in 479 B.C.E., when a large Greek army marched north from the Peloponnese. It met the Persians at Plataea, where the Spartan commander, Pausanias, won a victory against considerable odds. Meanwhile the Persian navy retreated across the Aegean. The Greek fleet confronted them again at Mykale, where the Persians made discretion the better part of valor. They abandoned their ships rather than face the Greek triremes, but they were then defeated by the Greeks in a battle on shore. The westward expansion by Xerxes was brought to a conclusive end. The Greek colonies in Asia Minor remained under Persian control, and the attempt to recover them continued for many years. An early success was the liberation of Byzantium, at the mouth of the Black Sea, in 478. Sparta was not interested in naval expeditions against the Persians in Asia, so the leadership of the Greek forces passed to Athens and the Delian League. By 448 B.C.E., the Persians had been cleared from all the Greek territories. There is some evidence that in that year a formal agreement, known as the Peace of Kallias, was reached which excluded the Persian fleet from the Aegean and guaranteed the independence of the Greek states of Asia Minor. Adapted from “The Greco-Persian Wars,” HistoryWorld, http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ab69. 4 The great wealth that Athens accumulated after the Greco-Persian Wars as it became an imperial power and the holder of funds for the Delian League was in part put to use rebuilding the city, and in particular the acropolis (the sacred center). The famous Parthenon was built during this time.