File - Eric DeMoura's E

advertisement

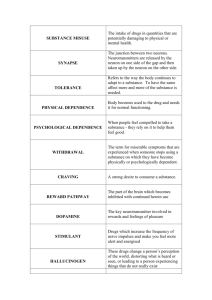

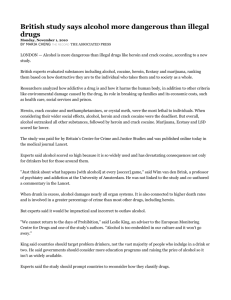

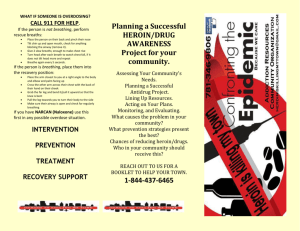

DeMoura 1 Eric DeMoura Professor Bedell CAS 137 H October 20, 2012 Paradigm Shift: Perception of Heroin Users and the Introduction of the Needle Exchange Program. Diacetylmorphine, or more commonly known on the streets as heroin, is an opiate generated from poppy seeds found mainly in Southeast Asia. Heroin can be used in a number of ways, including snorting, sniffing, or smoking, but the main route of administration of the drug is injecting it into one’s veins with a syringe. The outcome of the injection of this narcotic is a “surge of euphoria, the ‘rush,’ accompanied by a warm feeling of the skin, heaviness of the extremities, and clouded mental functioning” i(Drugabuse.org). Continuous use of heroin leads to increased tolerance of this poison, and users of heroin are at extremely high risks of becoming dependent on it. Addicts of course are at a higher risk to the numerous health conditions related to heroin use, including “fatal overdose, spontaneous abortion, collapsed veins and… infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS and hepatitis.” When Injection Drug Users, or IDU’s, share needles for their habit, they multiply the risks of contracting something as serious as the likes of HIV or hepatitis significantly. Due to an explosion in the 1970-80’s in the number of heroin addicts in the United States, coupled with an outbreak of the Hepatitis C virus and the emergence of the HIV, the government shifted its approach from one solely focused DeMoura 2 on heroin use as a criminal act to one that also considered its vast health implications, resulting in the Needle Exchange Program. Opiates have been in use in American culture since the nineteenth century. As morphine, the earliest derivative of poppy flowers, was prescribed as a painkiller by doctors during medical operations, as well as traumatic injuries. Its effectiveness was optimized in 1843 when Alexander Wood, a doctor from England discovered the new technique of administration of the narcotic through a syringe, injected straight into the bloodstream. The first mass-exposure to morphine occurred after the Civil War, when veterans were treated with heavy doses of morphine, and the number of addicts in the country sky rocketed, to the point where “tens of thousands of Northern and Confederate soldiers became morphine addicts” ii(Narconon.org). In 1874, C.R. Wright became the first to synthesize heroin by boiling morphine over a stove, in an attempt to create a “safe, non-addictive substitute” (Narconon.org) for heroin. Heroin was sold as a cure for alcoholism, tuberculosis, and common colds, among other things, until the 1920’s, when Congress finally recognized the dangers of the drug and banned it under the Dangerous Drug Act. By this time, however, it was too late, as there was an estimated 200,000 heroin addicts in the United States by 1925 (Narconon.org). This number would level off, and some experts even go as far as to say the number would drop, until the 1970’s, and the Vietnam conflict. In an attempt to stop the spread of Communism in Southeast Asia, the United States and France not only supplied drug lords in the region with arms and ammunition, but also provided transportation for their prized export, opium. East DeMoura 3 coast cities such as New York and Boston were (and continue to be) the main inheritors of this plague, and the number of heroin addicts in the United States would reach an all time high, with an estimated 750,000 people becoming dependent on it (Narconon.org). There was little sympathy for these addicts at the time, as popular formulations in the early 1970’s “emphasized peer group pressure… and self-destructive themes” (Khantzian, 1259)iii to explain the nature of drug addiction. Basically, it was a worldly view that if one was dependent on a hard narcotic, such as heroin, it was because one was a weak, or even evil person, who had no one to blame but themselves. However, psychoanalytic studies done in the 1970’s identified “psychological vulnerabilities, disturbances, and pain are predispositions for individuals and drug dependence” (Khantzian, 1259). This change in perception of drug users was a critical step in the development of rehabilitation centers and the Needle Exchange Program, but it was not the most significant trigger. The 60’s and 70’s were a unique time in American history, to say the least, with the “free love” and experimental drugs that accompanied it. It was a time when the sharing of needles was commonplace among America’s youth, because quite honestly the repercussions of distributing injection-based narcotics to several people with a single syringe were unknown. The sharing of needles in this time frame would coincide with an incredible number of cases of Hepatitis C, but that is not to say that this was a coincidence by any means. It takes ten to thirty years for chronic liver diseases, the main sign of HepC, to develop iv(CDC.gov), which is an incredibly obvious indication that the sharing of needles caused the outbreak. DeMoura 4 During the 1960-80’s, the peak of the needle-sharing years, the average number of cases of HepC was an astounding 240,000 cases a year – compared to an estimated 30,000 cases in 2000 (CDC.gov, 3). This happened to just the tip of the disease iceberg, so to speak, as an HIV epidemic hit the country in the early eighties. HIV was first discovered in homosexual men, and this lead to a stigmatism in the gay community, one that only homosexuals could contract the HIV or AIDS virus. The idea that only the homosexual community could fall victim to the newly found virus was such a wideheld commonplace that it was originally coined GRID, or “gay-related immune deficiency” in 1982 (Avert.org)v. It wasn’t until a newborn baby, who had had multiple blood transfusions, died of AIDS, that it was determined that “AIDS was caused by an infectious agent” (Avert.org) and was not just applicable to the gay community. By the next year, those seen as major-at-risk individuals included -along with homosexuals - Haitians, hemophiliacs, and heroin users. In 1983, the number of cases in the United States had risen to over 3,000, an incredible spike considering as of July 1982, there were only 450-recorded diagnoses (Avert.org). Scientists and activists took to attacking the problem immediately in Europe, and one of the first institutions put in to stop the spread of this epidemic was a needle exchange program, started in Amsterdam in 1984. The project spread to the United States in 1985, and has grown ever since. This project illustrates the train of thought that accompanies heroin users. No longer do we, on a community scale or government scale, deny the responsibility we must take in terms of public health. We can no longer take the stance that heroin DeMoura 5 addicts are only harming themselves by using their injection methods, because the rates of terrible diseases, like Hepatitis C and the HIV, have skyrocketed as heroin usage rates have raised. As of 2000, nearly one third of all HIV/AIDS cases in the United States were directly or indirectly (indirect as when a pregnant mother continues to do heroin, resulting in an infected and addicted child) related to injection drug users (Vlahov & Junge)vi. This is a staggering number, but one which makes sense in the context of the world at the time, as there were only 110 Needle Exchange Programs, or NEP’s, in all of North America. This number doubled in the past ten years, with there now being over 220 such programs in the United States alone (Vlahov & Junge). Overall, data shows that NEP’s have greatly lowered the number of positive tests of HIV/AIDS among injection drug users, with a report from the New Haven NEP showing that participants in the program have a 33% less likely chance to contract the deadly disease (Vlahov & Junge). A study from Tacoma, Washington, displayed similar results, showing that those who did not participate in NEP’s saw their chances of contracting Hepatitis C increase seven-fold (Vlahov & Junge). Users of heroin are able to legally attain clean needles at these health centers, which is a monumental change in the heroin addict landscape, because before these outbreaks, prescriptions were needed to attain syringes and needles from health centers or hospitals, and arrests for the possession of such paraphernalia was common. The attitude has certainly changed since then however, and as of 2006, 48 states in the United States had authorized needle exchange without prescriptions, and as of 2012, 35 states had a legal syringe exchange program run by the state government. One of the biggest healthcare issues of the DeMoura 6 late nineties/early twenty-first century was whether these programs should be funded by the national government. Originally, in 1988, federal funding of these programs was banned, but this band was lifted in 2009. However this was short lived, as the ban was reinstated by Congress in 2011, leaving state governments to both fund and run these programs at their own will. All these programs are not intended to promote the use of heroin – in Massachusetts, for example, one of the centers of opiate (OxyCotin, heroin, etc.) use on the East Coast, penalties for the possession of heroin range from two to twenty years, depending on the amount on one’s person. It should be made clear that heroin use is - as it was in 1970, with the passing of the Controlled Substances Act, deeming it a Schedule I drug – still viewed as a criminal act in our country, as it should be. However, it is no longer a case of protecting the individual user’s health, but rather a pubic health and safety concern. This paradigm recognizes that individuals who seek help and are, at the very least, trying to reduce the amount of harm to others, and therefore should not be denied of this privilege. Many centers offer some sort of rehabilitation to those who come forward and participate in the NEP, and again, this rehabilitation is two-fold in its purpose. It is not only seen as morally right to help our fellow human beings, but it is extremely cost effective as well. It is estimated that health care costs associated with hepatitis-related liver disease costs an upwards of $600 million dollars annually (CDC.gov). It is also estimated that a person living with HIV/AIDS spends approximately $200,000 dollars for treatment in their lifetime (aidsaction.org)vii. As of 2012, the most recent data collected showed that in 2008, almost 1.2 million Americans were living with an HIV infection (aids.gov). This number comes out to DeMoura 7 an astounding $240 billion dollars spent on HIV treatment, one third of which, as previously mentioned, can be attributed to injection drug users. This is still a mindblowing number, with nearly $80 billion dollars annually being spent on injection drug users/HIV patients a year. When compared to $37 million, the estimated amount necessary to run every needle exchange program in the United States in a year ($169,000 per program x 220 programs in the U.S.), the number looms even larger. The biggest issue today with needle exchange programs is the question of whether or not we are actually solving the issue at the heart of the problem, or simply finding lazy ways to curb it’s growth. Although there is significant evidence which suggests that these programs, which make needle and syringes easily attainable, do not promote heroin use in communities, it is fair to question whether this is valid or not. However, what cannot be questioned is the curtailing of these terrible diseases, as well as the spreading of awareness of public safety. This shift in thought from one of a solely criminal outlook to one in which public safety was seriously considered was a significant milestone in the history of injection drug use in not only the United States of America, but the entire world DeMoura 8 Works Cited AIDS Action. Needle Exchange Facts. June 2001. 24 October 2012 <www.aidsaction.org/legislation/pdf/policy_facts-needle_exchange2.pdf>. IDU/HIV Prevention. Viral Hepatitis and Injection Drug Users. September 2002. 24 October 2012 <www.cdc.gov/idu/hepatitis/viral_hep_drug_use.pdf>. International HIV/AIDS Charity. History of AIDS up to 1986. 2011. 24 October 2012 <www.avert.org/aids-history-86.html>. Junge, David Vlahov & Benjamin. Public Health Reports. June 1998. 24 October 2012 <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1307729/pubhealthrep000300079.pdf>. Khantzian, Edward J. Self Medication Hypothesis of Addictive Disorders: Focus on Heroin and Cocaine Dependence. November 1985. 24 October 2012 <www.ap.psychiatryonline.org/data/journals/AJP/3404/1259.pdf>. Narconon International. History of Heroin and Opium Use And Abuse. 2010. 24 October 2012 <www.narconon.org/drug-information/heroin-timeline.html>. National Institue of Drug Abuse. Heroin. October 2012. 24 October 2012 <www.drugabuse.gov/drugfacts/heroin>. (National Institue of Drug Abuse) (Narconon International) iii (Khantzian) iv (IDU/HIV Prevention) v (International HIV/AIDS Charity) vi (Junge) vii (AIDS Action) i ii