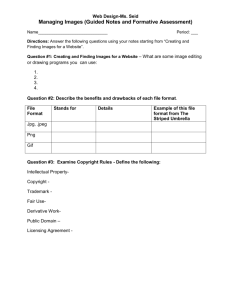

Scenario Planning Techniques

advertisement

Leeds University Business School A Pragmatic Science Evaluation of Scenario Planning for Strategic Intervention Professor Gerard P. Hodgkinson Dr Mark P. Healey Centre for Organizational Strategy, Learning and Change, Leeds University Business School Presented at Newcastle University Business School 16thHodgkinson April 2008 © Copyright and Healey 2007 Overview Background to scenario planning Design science approach to strategic intervention Multi-level theoretical framework Research process Illustrative findings from ongoing interview study Implications for research and practice © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 The cognitive challenges of organizational innovation and adaptation • NASA • The London Stock Exchange • UK Prison Service • Prudential • Marks and Spencer PLC © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Major contention • Each of these cases illustrates one or more fundamental, generic processes highly pertinent to managing technology, innovation, and/or change • In each case key decision makers were unwilling or unable to recognize that the assumptions and beliefs informing their actions were deeply flawed © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Strategic Drift Source: G. Johnson (1987). Strategic Change and the Management Process. Oxford: Blackwell. (Adapted with permission from the author) Environmental Change Amount of Change PHASE 1 Incremental Change PHASE 2 Strategic Drift PHASE 3 Flux TIME © G. Johnson 1987 PHASE 4 Transformational Change or Demise Why does history repeat itself? (Or why do organizations not learn?) • Cognitive bias • Cognitive inertia • Group think • Strategic drift • Escalation of commitment © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Cognitive bias and cognitive inertia • Brain is a limited capacity processor • Therefore, reality is represented in simplified forms (‘mental models’) • Simplification strategies used in the construction of mental models can lead to biased judgments and decisions • Once formed these models act as filters and are highly resistant to change © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Cognitive Bias and Inertia In Strategic Decision Processes • Strategists may become overly dependent on their mental models, thereby failing to notice key external changes until their organization's capacity for successful adaptation has been seriously undermined (Barr and Huff, 1997; Barr et al., 1992; Hodgkinson, 1997, 2005; Reger and Palmer, 1996) • To minimize this danger they should periodically engage in processes of reflection and dialogue, in an attempt to attain the requisite variety in mental models necessary in order to anticipate the future and develop a strategically responsive organization (Morecroft, 1994; Senge, 1990) © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 What is Scenario Planning? A group of techniques yielding depictions of ‘plausible futures’ to inform strategic decision making, broaden strategic thinking, and aid organizational learning Pioneered by Royal Dutch/Shell from mid1960s. Widely used as an aid to decision analysis, forecasting, and strategic planning (Schoemaker 1993) Popular in Europe (Malaska 1985, US (Linneman & Klein 1983), and UK (Hodgkinson et al. 2006) © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 ‘Which of the following analytical tools were applied during the workshop?’ SWOT 62.0% Stakeholder analysis 30.0% Scenario planning 28.5% Market segmentation 22.6% Competence analysis 21.5% PEST(EL) analysis 17.2% Value chain analysis 15.1% BCG Matrix 8.6% Porter’s Five Forces 8.5% Cultural Web 5.5% McKinsey’s 7 S’s Other 5.3% 12.5% Hodgkinson et al., LRP. © 2006 Elsevier limited Objectives To develop new academically rigorous knowledge enabling users and would be users of scenario-planning and related approaches to appreciate the complexities involved in the design of successful interventions Three lines of inquiry, broadly grouped under a design science umbrella, variously addressing aspects of team design, facilitation, group dynamics and information processing – with a view to enhancing the effectiveness of scenario-based approaches in fostering innovation and organizational adaptation © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Scenario Planning Techniques • Systematic yet highly flexible • Highly participative, involving extensive data gathering and reflection, both at an individual and collective level • Force strategists to explicitly confront the changing world and consider its implications for the current strategy • Use of speculation and human judgement in an attempt to gain fresh insights and “bound” future uncertainties • Directed toward stretching decision makers’ thinking about their organization’s business model and its future environment, overcoming corporate blind-spots, and enhancing strategic flexibility • Benefits of the ‘strategic conversation’ © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Scenario planning: A four step process (after van der Heijden) 1. Identify the current competencies of the organization and how these are configured to add value (‘the business idea/virtuous circle’) 2. Identify key future trends and classify these into ‘uncertainties’ (things that might happen) and ‘predetermineds’ (developments in the pipeline) 3. Develop multiple scenarios that capture the predetermineds and uncertainties 4. Expose the current business idea to the scenarios and consider the implications (attempting to bound uncertainty rather than predict it in probabilistic terms) After: van der Heijden (1996), Scenarios: The art of strategic conversation, Chichester: Wiley. © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 The Generic Business Idea Understanding evolving needs in society Entrepreneurial invention Resources “Unique, difficult to emulate Distinctive elements that differentiate from competencies competitors” Results Competitive Advantage “Basis of value creation: e.g. product/ service differentiation or cost leadership produced by competencies” Source: van der Heijden, K. (1996), Scenarios: The art of strategic conversation, Wiley, p. 69 The Kinder-Care Business Idea Professional/ management/ financial resources Land/buildings Innovative child care Retention exteachers Teacher satisfaction Revenue Pay for service Parents’ good feelings Reputation Working parents -ve Parents’ financial resources Source: van der Heijden, K. (1996), Scenarios: The art of strategic conversation, Wiley, p. 71 Identifying uncertainties and predetermineds UNCERTAINTIES Elements/events in the business environment that might develop in different ways E.g. SMS text messaging continues to grow versus becomes obsolete; genetic modification of embryos is legalised versus embryonic modification stays outlawed PREDETERMINEDS Elements/events in the business environment considered predictable E.g. Population continues to age; new gas pipeline opens in Russia © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Developing multiple scenarios • Based on the previously identified uncertainties & predetermineds • Organize the selected uncertainties into a matrix, with each cell describing a distinct future based on uncertainties unfolding differently • Write short narratives describing each scenario; incorporate predetermineds and other uncertainties if appropriate • Scenarios should be internally consistent and plausible © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Building a scenario matrix U2: Information use by customers U1: Changes in the newspaper industry business model Traditional – based on advertising revenue New – sale of information and advertising separated Minor change Business as usual … with a twist Unbundling of information and advertising Radical change Consumers in control Cybermedia Source: Schoemaker & Mavaddat (2000) ‘Scenario planning for disruptive technologies’, in Day et al (Eds.) Wharton on Managing Emerging Technologies, New York: Wiley, p.224 Example Narrative scenario ‘Cybermedia’ “Technology has progressed rapidly as predicted by futurists; the ways in which consumers use and access information have changed fundamentally. Most consumers either have customized newspapers printed at their homes or access their news through high-tech Internet appliances. The lines between newspaper and television and other media channels have blurred, as multi-media presentations of textual and visual information proliferate. Business models have changed too: newspapers derive revenue from national advertisers, subscriptions, transaction services, and new businesses such as being an intermediary for high-end purchases, high-technology classifieds, and customer profiling. With the rise in electronic distribution, newspapers are struggling to sell their antiquated printing presses – generally at rock-bottom prices.” Source: Schoemaker & Mavaddat (2000) ‘Scenario planning for disruptive technologies’, in Day et al (Eds.) 2007 Wharton on Managing Emerging Technologies, New York: Wiley, p.229 © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 Expose business idea to scenarios Understanding the environment (scenarios) Understanding the institution (business idea) Is this the right company for these future environments? If not: address competencies If so: address strategic choices © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Variant scenario planning techniques • Many variations of scenario planning techniques, beyond the van der Heijden (1996) approach • Range from quantitative, probabilistic applications with a forecasting emphasis to more qualitative approaches emphasizing the cognitive and/or interpersonal and organizational learning benefits • Range from half-day ‘frame-breaking’ sessions involving select top management team members to lengthy 6-12 month ‘visioning’ exercises involving greater numbers of different stakeholders © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Do Scenario Techniques Work? • Lots of anecdotal evidence, including documented case studies of success (e.g. Wack’s (1984a, 1984b) account of Shell) • Some laboratory evidence for influence of scenarios on stretching decision makers’ judgements (see Healey & Hodgkinson, 2008) • But, evidence base underpinning scenario planning needs examining and augmenting • Mainly case studies from practising advocates. Various positive outcomes are ascribed to scenario processes • Despite benefits claimed by advocates, little known about conditions under which scenario planning thrives or fails (Mintzberg 1994; cf. Hodgkinson & Wright 2002; Healey & Hodgkinson, 2008) • More documented cases of failure are needed … © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Why Independent, Rigorous Scientific Scrutiny? Potentially harmful effects to individuals and organizations, for example: Mild irritation (wasted resources) Severe psychological trauma (bleak future) Short-term relationship difficulties (within the team) Lasting damage (beyond the team, triggered by irreconcilable differences) © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Three Lines of Inquiry • Refinement of the mental model concept to develop techniques that trigger meaningful cognitive change (Chattopadhyay, Hodgkinson & Healey, 2006; Healey & Hodgkinson, 2008) • Development of insights into the design of facilitation processes and team selection, based on an extrapolation from the field of personality and social psychology (Hodgkinson & Healey, 2008) • Critical incident study of drivers of past successes and failures, as reported by ‘expert’ facilitators (on going) © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Optimizing the scenario team and facilitation processes Please consider the following issues: Who should be involved in scenario planning events, and why, where the aim is to stimulate organizational innovation and change? What might be the consequences of only involving top-level managers? What might be the consequences of only involving middle-level managers? What might be the consequences of attempting to involve individuals from a mix of levels and departments within the organization? What might a desirable scenario team look like, and what would be the consequences? Who should facilitate the exercise and why? © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Optimizing the scenario team and facilitation processes • Consider how your answers to the previous questions might affect the: Quality of debate about strategic issues (including scenarios generated) The extent of open discussion and planning The extent of consensus regarding strategic priorities and future strategies The nature and extent of conflict over strategic issues The level of acceptance of need for change The effectiveness of the implementation of the outcomes of the scenario exercise © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Strategy workshops survey Hodgkinson et al., Long range planning. © 2006 Elsevier limited © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Strategy workshops survey Hodgkinson et al., Long range planning. © 2006 Elsevier limited © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Learning From ‘Failure’: The Case Of Beta Co • The only published case to date of systematically documented failure (for further details see Hodgkinson and Wright, Organization Studies, 2002) • Provider of specialist support service to businesses in an industry marked by radical transformation • Potentially, the company’s main offering could soon be obsolete • Our approach broadly followed van der Heijden (1996) © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Learning From ‘Failure’: The Case Of Beta Co • Nine individuals took part including the CEO, six other members of the senior management team, and two operational staff • Interviews with the individual participants revealed marked differences of interpretation • Intention that these data should serve as the basic starting point for debating the business idea, prior to moving forward with scenario work • However, severe difficulties were encountered from the outset © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Learning From ‘Failure’: The Case Of Beta Co • The CEO frequently intervened, in an attempt to control both the processes and outcomes, eventually withdrawing from all but the final stage of the exercise • Clear evidence of dysfunctional processes at work, as depicted in the conflict theory of decision making and the literature on psychodynamic aspects of executive behaviour • Interpretation strongly supported by content analysis of extensive field notes © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Moving Beyond the Beta Co. Case • Need to document more failures (and successes) to learn about the effects of context • Additional factors need to be investigated • Need for a guiding framework • Need for insights into the design of future scenario planning interventions © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Research Process Started with insights from Hodgkinson & Wright (2002) Conceptualization of scenario planning as input-processoutput model, underpinned by extensive review of wider management and social science literatures Design principles derived from framework and theorizing Empirical study as an approach to field testing these principles, with a view to validating, elaborating and refining them © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Outer context (social, economic, political and technological) Facilitator will & skill Scenario team processes and outcomes Team composition Inner context (culture, structure and micro-politics) Figure 1: Guiding Framework for Design Science Approach Design science approach After Simon 1969, Sciences of the Artificial; also Dunbar & Starbuck (2006), Romme & Endenburg (2006), van Aken (2004, 2005) Where evidence is lacking, develop design propositions from robust, established bodies of theory and research in the wider management and social sciences Testing of these principles in action in diverse field settings At present, we have neither of these in relation to scenario planning or strategy workshops more generally Hence, our ongoing work … © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Design science approach Development of a systematic, evidence-informed approach to engineering cognitive tasks directed to deeperlevel/more effortful strategic deliberation (Chattopadhyay, Hodgkinson & Healey, 2006; Healey & Hodgkinson, 2008) Importance of who gets involved and how for creating conditions conducive to effective group information processing and cooperative working (Hodgkinson & Healey, 2008) Approaches to the management/facilitation of sub-optimally configured scenario teams © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Research Process Started with insights from Hodgkinson & Wright (2002) Conceptualization of scenario planning as input-processoutput model, underpinned by extensive review of wider management and social science literatures Design principles derived from framework and theorizing Empirical study as an approach to field testing these principles, with a view to validating, elaborating and refining them © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Configuring the scenario team • Variety of background/knowledge/skills within team • Popular approaches concentrate on this, but ignore potentially dysfunctional information processing consequences of bringing together disparate groups • Two ways to avoid problems with diverse teams: Manage social identity processes Personality configuration © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Background characteristics and social identity effects • When teams come together with different backgrounds (e.g. age, experience, function), members may cling to their existing subgroup identities, creating conflict between subgroups (e.g. members from finance versus members from marketing) • Conflict can disrupt open communication and critical, constructive dialogue about the future, which are critical to scenario planning © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Background characteristics and social identity effects • To avoid harmful conflict between subgroups: Select team members who identify with multiple functional areas within the organization Avoid configuring the scenario team into factions • With diverse/factional groups, one solution is to build and emphasize the common identity of the scenario team: Emphasize shared fate of all participants/organization Set and highlight shared goals Structure tasks to facilitate collaboration between members of different subgroups Build collective (“we’re in this together”), rather than divisive (“it’s them versus us”) mentality © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Influence of Personality • Personality of scenario team • Five factor model of human personality • Tools to assess personality and inform team selection and facilitation techniques • Select scenario team for appropriate blend of personalities • If selection infeasible, need to adapt facilitation process to the personality profile of the team © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Implications of Personality Composition for the Design of Scenario Planning Teams Extraversion Openness Trait Key Descriptors a Relevant Indicative Findings Intellectual, creative, complex, imaginative, artistic (vs. unintellectual, unimaginative , simple, imperceptive, shallow) High Openness is associated with divergent thinking, constructive dissent and the effortful processing of multiple perspectives (McCrae 1996) Talkative, assertive, energetic, bold (vs. shy, quiet, reserved, inhibited, withdrawn) Individual Extraversion predicts the constructive challenging of others’ perspectives (LePine and Van Dyne 2001) and moderates the negative effects of demographic dissimilarity (Flynn et al 2001) Managers high in Openness are tolerant of ambiguity and interpret change as less stressful; thus they cope better with, and are less likely to disengage from, change activities (Wanberg & Banas 2000) Teams comprising members higher in Openness communicate more effectively (Barry and Stewart 1997) and show greater agreement seeking and consensus (Amason and Sapienza 1997) Extraversion predicts socio-emotional and task inputs in teams. Hence, teams comprising moderately extravert members, or a moderate proportion of high extraverts, outperform those dominated by high or low extraverts (Barrick et al 1998; Barry and Stewart 1997) Hypothesized Role in Scenario Teams Scenario teams high in Openness will experience less anxiety and cope better when responding to future contingencies, generate and analyse more effectively challenging scenarios, be more willing to accept diverse perspectives, will generate alternative strategic responses of higher quality with greater fluency, and will explore more readily new strategic directions than teams low in Openness Scenario teams comprising moderate Extraversion members, and teams with a moderate proportion of high Extraversion members, will engage in more effective elaboration regarding strategic issues than teams comprising a majority of high or low Extraversion members Source: Hodgkinson and Healey (2008). ‘Toward a (pragmatic) science of strategic intervention: Design propositions for scenario planning, Organization Studies, © Sage Publications 2008 Implications of Personality Composition for the Design of Scenario Planning Teams Agreeableness Neuroticism Trait a Trait Key Descriptorsa Relevant Indicative Findings Anxious, moody, envious, emotional, irritable (vs. unemotional, relaxed, imperturbable , unexcitable, undemanding) Neuroticism reduces the propensity to engage in analytical behavior (Stewart, Fulmer, and Barrick 2005) Kind, cooperative, sympathetic, warm, helpful (vs. cold, unkind, distrustful, harsh, rude) In politicized contexts, low Agreeableness individuals are less cooperative and eschew organizational goals (Witt et al. 2002) Neuroticism heightens psychological distress during organizational change (Moyle and Parkes 1999) and increases escalation of commitment (Wong et al 2006) Unable to inhibit their egoistic impulses, a single highly Neurotic individual in a management team can reduce social cohesion, thus undermining its performance (Barrick et al. 1998) The average level of team agreeableness is positively associated with social cohesion, open communication, conflict resolution, and task performance (Barrick et al. 1998; Neuman and Wright 1999) Hypothesized Role in Scenario Teams The presence of high Neuroticism team members will inhibit elaboration in constructing and analysing scenarios, constrain the creative generation of appropriate strategic responses, and increase the likelihood of dysfunctional defensiveavoidance behaviours, thereby derailing the intervention process Moderately agreeable teams will exchange freely diverse information and perspectives and engage in constructive debate when constructing and analysing scenarios. Conversely, overly agreeable teams will eschew such debate Team learning negatively is affected when teams are composed of individuals high in Agreeableness (Ellis et al 2003) descriptors are sample marker adjectives taken from Goldberg (1992) Source: Hodgkinson and Healey (2008). ‘Toward a (pragmatic) science of strategic intervention: Design propositions for scenario planning, Organization Studies, © Sage Publications 2008 Trait Key Descriptors a Conscientiousness Implications of Personality Composition for the Design of Scenario Planning Teams Organized, systematic, thorough, neat, efficient (vs. disorganized , careless, inefficient, impractical, sloppy) a Trait Relevant Indicative Findings Conscientiousness is related positively to work performance at the individual (Barrick and Mount 1991) and group (Neuman and Wright 1999) levels of analysis Teams make the most accurate decisions when their leaders and all members are high in Conscientiousness (LePine et al. 1997) High levels of intra-team variance in Conscientiousness is associated with perceived input inequalities, heightened conflict and reduced team performance (Barrick et al 1998) Hypothesized Role in Scenario Teams Scenario teams comprising a majority of high Conscientiousness members will engage more effortfully in scenario construction and analysis, increasing the likelihood of attaining the requisite cognitive outcomes descriptors are sample marker adjectives taken from Goldberg (1992) Source: Hodgkinson and Healey (2008). ‘Toward a (pragmatic) science of strategic intervention: Design propositions for scenario planning, Organization Studies, © Sage Publications 2008 Illustrative Design Propositions • Design Proposition 3 (Identity Management): When working with an informationally diverse scenario team, to reduce inter-subgroup bias and facilitate the elaborative processing required for effective scenario construction and analysis, stimulate superordinate recategorization by emphasizing the shared fate of the scenario team and establishing common goals • Design Proposition 4 (Personality Configuration): To ensure effective coping with change and willingness to explore new avenues of inquiry, and facilitate novel thinking, the exchange of diverse perspectives and ideas, meaningful consideration of challenging scenarios and the generation of high quality responses to scenarios, wherever possible select participants high in Openness to Experience © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Facilitating Scenario Teams with Different Personality Profiles • When selecting the team on the basis of personality is infeasible, it is important to be aware of the profile of the team and its likely effects • Can help overcome shortcomings in composition by adapting facilitation to the nature of the team © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Adapting Facilitation to the Personality Profile of the Team • When dealing with a scenario team comprising members low in Openness, facilitators should introduce techniques directed toward fostering innovative thinking in order to generate challenging and plausible scenarios and creative strategies for dealing with the contingencies so envisioned Involve ‘remarkable people’ Use devils advocacy when generating scenarios Introduce dialectical thinking tasks when analyzing how the organization might best respond to scenarios © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Adapting Facilitation to the Personality Profile of the Team • When dealing with a scenario team dominated by high Extraversion participants, the role of the facilitator is to ensure that debate and the exchange of perspectives regarding strategic issues remains within functional levels, and does not degenerate into interpersonal conflict that might create rifts and limit meaningful dialogue • When dealing with a scenario team dominated by low Extraversion members (i.e. introverts), facilitators need to develop a climate of mutual trust within the scenario team, to encourage participants to be forthcoming with their opinions regarding strategic issues © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Critical Incident Study Critical incident technique (Flanagan 1954) Collation of successful and unsuccessful scenario episodes from experienced facilitators Narrative retrospective reports provide rich detail of micro-strategy processes and behaviours Incidents give insight into processes and outcomes Cross section of organizations: public/private; SMEs/multinationals; manufacturing/service; dynamic/stable environments © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Outer context (social, economic, political and technological) Facilitator will & skill Scenario team processes and outcomes Team composition Inner context (culture, structure and micro-politics) Figure 2: Guiding Framework for Critical Incident Study Model of the Scenario Planning Process INPUTS/ CONSTRAINTS PROCESSES Organizational outcomes Environmental change • Nature of change in task environment: discontinuous versus continuous • Rate of change in task environment: low, moderate, high Structural responsiveness of the organization • Internal structures, systems, & routines • Internal politicization • Psychological climate Composition of scenario team • Informational & demographic diversity • Personality composition (Big Five) OUTPUTS • Organizational change: successful versus unsuccessful • Strategic adaptability: high versus low Scenario team processes • Inter-subgroup processes • Politicking & coalitional behaviour • Intra-team conflict & elaboration • Team information processing • Strategic problem solving & decision making activities Facilitation • Intervention design • Managing behavioural dynamics • Stimulating team elaboration • Political will and skill Intervention outcomes • Mental models: revised versus reinforced • Strategic ideas, decisions, solutions: high versus low quality • Strategic alternatives: robust versus weak • Extent of strategic consensus: high versus low • Commitment to strategic change: high versus low Critical incident 1 – Multinational Manufacturer “It was a big manufacturing organization operating in Europe. The MD had a massive ego … We did a nine-month programme, running a workshop in Merseyside. The problem was perceived to be structure … The groups were working to identify key issues for [their sector] to enable them to operate globally. [As part of the scenario process] we gave them magazines and posters to build pictures of the future … They were very creative – not what I’d expect from a bunch of engineering managers. The chairman came up to me at 4pm and told me that this was extraordinary. Then the MD arrived, and told people to stop what they are doing. People were tall and upright, but by the time he had finished they were all looking at the floor. The effect was like a boiling water enema - the more junior people thought they had been betrayed, the senior people thought ‘oh he’s done it again’. There was blubbing in the loo and that sort of thing … He was in charge – he was top dog, he was going to tell them what to do, he knew all the answers and the answer was cost cutting … There was a long internal process to correct this. The project as it was defined didn’t happen. Nobody wanted to go on the [strategy workshop] teams. It was a huge waste of money and time and everything else.” (Facilitator, negative incident) © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Critical incident 2 – Small ICT service provider “[The organization concerned] was a bit like a dysfunctional family. There was antagonism between departments and all kinds of stuff going on … They didn’t benefit from the outputs in the way that other organizations did. A lot of organizational change had happened, which was very fresh and painful. There was a lot of uncertainty and discomfort. Lots of infighting … when we had a coffee break it was a bit like being at a family wedding. There were lots of bitchy asides … they used it [the SP exercise] as an opportunity to bring out aggressions that were already there ... But if you look at the internal drivers [of future change in the business environment] that they mentioned, they were communication between departments, organizational culture, staff morale, staff attitude, staff understanding of the organization. You could tell what was going on in that organization.” (Facilitator, negative incident) © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Critical incident 3 – Multinational technology manufacturer “It was a two day exercise with the heads of NPD and strategy for technology x [to look at impact of technological change]. We had a really good client group ... they were willing to play with and try out ideas ... this created good chemistry on the day. The forces of personality played a role ... they were a good group, whereas other groups have not been so good. There was sharing and exploration of the different poles rather than slanging matches between the different camps. There was something about the playful quality of the day – a willingness to try new things, and enlisting the team into them ... the framing of the day helped this. And the process was successful. It wasn’t just the information they took away that was valuable – it was the changing of their way of thinking [about their strategy in relation to technological change]”. (Facilitator, Positive incident) © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Model of the Scenario Planning Process INPUTS/ CONSTRAINTS PROCESSES Organizational outcomes Environmental change • Nature of change in task environment: discontinuous versus continuous • Rate of change in task environment: low, moderate, high Structural responsiveness of the organization • Internal structures, systems, & routines • Internal politicization • Psychological climate Composition of scenario team • Informational & demographic diversity • Personality composition (Big Five) OUTPUTS • Organizational change: successful versus unsuccessful • Strategic adaptability: high versus low Scenario team processes • Inter-subgroup processes • Politicking & coalitional behaviour • Intra-team conflict & elaboration • Team information processing • Strategic problem solving & decision making activities Facilitation • Intervention design • Managing behavioural dynamics • Stimulating team elaboration • Political will and skill Intervention outcomes • Mental models: revised versus reinforced • Strategic ideas, decisions, solutions: high versus low quality • Strategic alternatives: robust versus weak • Extent of strategic consensus: high versus low • Commitment to strategic change: high versus low Summary and Conclusions Summary • Organizations often fail to adapt and change because of cognitive inertia, escalation of commitment and groupthink • Scenario planning is a technique to facilitate strategic change: aim is to stretch thinking and aid learning • Various approaches to scenario planning, including the four step process (after van der Hiejden) • The evidence base for this and other approaches has been, hitherto, largely anecdotal • Work conducted by my colleagues and I at AIM Research/COSLAC has laid important foundations for taking the evidence base to a new level, while also providing some useful guidelines for practice © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Summary • Evidence base for, and recent advances in, scenario planning • Who is involved and how the exercise is facilitated matter: Configuration of the team in terms of member background characteristics and personalities (social identity and personality effects) will influence processes and outcomes Where team design is difficult, effective facilitation can overcome shortcomings in team configuration © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Recommended Reading 1. Delbridge, R. Gratton, L. Johnson, G. et al. (2006) The Exceptional Manager: Making the Difference. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Provides a useful overview of the concepts of inertia and strategic drift, and relevant background material on the cognitive and related challenges pertaining to innovation and decision making in organizations 2. Healey, M. P. and G. P. Hodgkinson (2008) 'Troubling futures: Scenarios and scenario planning for organizational decision making,' in Oxford Handbook of Organizational Decision Making. eds. G. P. Hodgkinson and W. H. Starbuck, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Outlines the cognitive benefits and pitfalls of multiple scenario analysis 3. Hodgkinson, G. P. and Healey, M. P. (2008) ‘Toward a (pragmatic) science of strategic intervention: Design propositions for scenario planning’, Organization Studies, 29, 435-457. An analysis of how team composition and facilitation can be designed to produce effective scenario planning processes and outcomes 4. Hodgkinson, Gerard P. and Paul R. Sparrow 2002, The Competent Organization: A Psychological Analysis of the Strategic Management Process, Buckingham: Open University Press. Provides a comprehensive analysis of the psychological and information processing challenges facing decision makers in contemporary organizations 5. Hodgkinson, G. P., R. Whittington, G. Johnson, and M. Schwarz 2006, "The Role of Strategy Workshops in Strategy Development Processes: Formality, Communication, Coordination and Inclusion," Long Range Planning, 39 (5), 479496. Reports findings from a large-scale survey of strategy workshop practices 6. Hodgkinson, Gerard P. and George Wright 2002, "Confronting strategic inertia in a top management team: Learning from failure," Organization Studies, 23 (6), 949-977. An entertaining and insightful case of a ‘failed’ scenario planning exercise, analysed from a decision making/psychodynamic perspective 7. Ringland, G. 1998, Scenario planning: Managing for the Future, Chichester: Wiley. Describes several case-studies of scenario planning in various contexts, illustrating various approaches to scenario planning that differ from that adopted in the class exercise 8. (A) van der Heijden, Kees 1996, Scenarios - The art of strategic conversation, Chichester: John Wiley. (B) van der Heijden, Kees, Ron Bradfield, George Burt, George Cairns, and George Wright 2002, The sixth sense: Accelerating organizational learning with scenarios, New York: John Wiley. Two books outlining the principles and practices of scenario planning from a learning perspective © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2008 2007 Leeds University Business School FURTHER INFORMATION Professor Gerard P. Hodgkinson Professor of Organizational Behaviour and Strategic Management, and Director, Centre for Organizational Strategy, Learning and Change (COSLAC), Leeds University Business School: gph@lubs.leeds.ac.uk Dr Mark P. Healey Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Organizational Strategy, Learning and Change (COSLAC), Leeds University Business School: busmph@leeds.ac.uk © Copyright Hodgkinson and Healey 2007