Systems Biology

advertisement

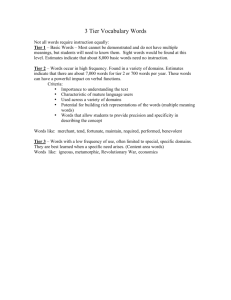

Bioinformatics: Applications ZOO 4903 Fall 2006, MW 10:30-11:45 Sutton Hall, Room 312 Jonathan Wren Systems Biology Lecture overview • What we’ve talked about so far – Pathways & network motifs – Simulating evolution in-silico – Cellular simulations • Overview – The ultimate goal of biology & bioinformatics is to tie it all together and understand the system – In the meantime, forced to live in the real world, we focus on tying a few things together Systems Biology – backers & attackers Though coined 40 years ago, a lot of people still ask, "What's that?" when the term systems biology comes up. "It is used in so many different contexts, nobody is really clear what you mean by it," says John Yates III, a professor at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif. He's not the only one stumped by the term's meaning. David Placek, president of Sausalito, Calif.-based Lexicon Branding, a company that cooks up names for pharmaceutical products such as Velcade and Meridia, says he's not so hot on the moniker. "Systems biology is just so general that it could apply to many things. When you're naming a category, the underlying principle is that if you make a statement like, 'I'm doing systems biology,' do people know what you're talking about?'“…… Volume 17 | Issue 19 | 27 Oct. 6, 2003, The Scientist What is “Systems Biology”? Is this just another name for “physiology”? The study of the mechanisms underlying complex biological processes as integrated systems of many interacting components. Systems biology involves (1) collection of large sets of experimental data (2) proposal of mathematical models that might account for at least some significant aspects of this data set, (3) accurate computer solution of the mathematical equations to obtain numerical predictions, and (4) assessment of the quality of the model by comparing numerical simulations with the experimental data. -(Leroy Hood, 1999) Institute for Systems Biology http://www.systemsbiology.org/ Why Systems Biology? • On the technology side (PUSH): Capabilities for highthroughput data gathering that have made us aware that biological networks have many more components than we previously surmised. • On the biology side (PULL): The realization that to the extent that we don’t characterize biological systems quantitatively in their full complexity, the scope and accuracy of our understanding of those systems will be compromised. (in classical experimental terms, the uncontrolled variables in the system will undermine our confidence in the conclusions we draw from our experiments and observations) Systems Biology vs. traditional cell and molecular biology • Experimental techniques in systems biology are high throughput. • Intensive computation is involved from the start in systems biology, in order to organize the data into usable computable databases. • Exploration in traditional biology proceeds by successive cycles of hypothesis formation and testing; data accumulates during these cycles. • Systems biology initially gathers data without prior hypothesis formation; hypothesis formation and testing comes during post-experiment data analysis and modeling. Genomics, Proteomics & Systems Biology Genomics Proteomics Systems Biology 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 Modelling Tools 9 7 # 5 3 1 65-69 70-74 75-79 80-84 Period 85-89 90-94 95-99 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • BIOSSIM (1968) ESSYN (1976) SCAMP (1983) SCOP (1986) METAMOD (1986) SIMFIT (1990) METAMODEL (1991) METASIM (1992) KINSIM (1993) GEPASI (1994) METALGEN (1994 ?) MIST (1995) METABOLIKA (1997 ?) METAFLUX (1997) SIMFLUX (1997) MNA (1998) CELLMOD (1998) FLUXMAP (1999) METATOOL (1999) VCELL (1999) From Klaus Mauch, University of Stuttgart Systems Biology is an integration of data & approaches Technologies to study systems at different levels • Genomics (HT-DNA sequencing) • Mutation detection (SNP methods) • Transcriptomics (Gene/Transcript measurement, SAGE, gene chips, microarrays) • Proteomics (MS, 2D-PAGE, protein chips, Yeast-2-hybrid, X-ray, NMR) • Metabolomics (NMR, X-ray, capillary electrophoresis) Each system has methods for modeling Pi Calculus Flux Balance Analysis Petri Nets Differential Eqs Each system has methods for modeling Boolean Networks Electrical Circuit Model Cellular Automata So how can we meaningfully integrate the data? System heterogeneity in size & timescale Atomic Scale 0.1 - 1.0 nm Coordinate data Dynamic data 0.1 - 10 ns Molecular dynamics Molecular Scale 1.0 - 10 nm Interaction data Kon, Koff, Kd 10 ns - 10 ms Interactions Cellular Scale 10 - 100 nm Concentrations Diffusion rates 10 ms - 1000 s Fluid dynamics System heterogeneity in size & timescale Tissue Scale 0.01m - 1.0 m Metabolic input Metabolic output 1 s – 1 hr Process flow Organism scale 0.01m – 4.0 m Behaviors Habitats 1 hr – 100 yrs Mechanics Ecosystem scale 1 km – 1000 km Environmental impact Nutrient flow 1 yr – 1000 yrs Network Dynamics Each of the scales does not fit together seamlessly • If one scale (e.g., protein-protein interactions) behaves deterministically and with isolated components, then we can use plug-n-play approaches • If it behaves chaotically or stochastically, then we cannot • Most biological systems lie between this deterministic order and chaos: Complex systems Man-made Complex Devices Intel Pentium 4 42 million transistors Man-made Complex Devices • The Intel Itanium 2 • 410 million transistors • Number of gates > 100 Million By 2007 both Intel and AMD are predicting dies with 1 billion transistors In terms of parts and interconnections, man-made devices will likely have comparable complexity to bacterial cells if not greater by around 2010 System Models Building computational models of systems seems more and more like a viable project. Such a project would bring a much clearer understanding of how systems are controlled and ultimately it should bring unprecedented predictive power. Are Biologists Ready? Xo S1 S2 S3 v S4 S5 S6 X1 Xo and X1 fixed, all reactions reversible, assume stable steady state. Are Biologists Ready? 50 % Xo S1 S2 S3 v S4 S5 S6 X1 What happens to the steady state? Xo and X1 fixed, all reactions reversible, assume stable steady state. Are Biologists Ready? 50 % Xo S1 S2 S3 v S4 S5 Typical replies: 1. Nothing happens. 2. Nothing happens unless it is the rate-limiting step. 3. The rate v goes down, but that’s all. 4. S3 goes up. 5. S4 goes down. 6. Species downstream of v go down. 7. Steady State flow changes but species levels don’t. 8. Xo and X1 change S6 X1 Are Biologists Ready? 50 % Xo S1 S2 S3 v S4 S5 S6 If we can’t understand this system how can we hope to understand: X1 Functional Motif Identification Computer simulation of EGF signal transduction PC12 cells. Frances Brightman, Simon Thomas and David Fell http://bms-mudshark.brookes.ac.uk/frances/fabweb5.htm 29 species Functional Motif Identification Computer simulation of EGF signal transduction PC12 cells. Frances Brightman, Simon Thomas and David Fell http://bms-mudshark.brookes.ac.uk/frances/fabweb5.htm 29 species Functional Motif Identification 27 components Functional Motif Identification As we begin to connect systems we can engage in inference • We move up the chain from data to knowledge by questioning, observing and then hypothesizing – These X genes are upregulated together, but are they interacting? – PPI network data suggests Y are – Are these Y part of a complex? – If they are always expressed together, that suggests maybe yes • As more data is integrated and systems linked together, this becomes easier Example of inference (a) An interaction network of Snz–Sno proteins of S. cerevisiae. The nodes represent proteins and the lines represent yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) interactions. The red nodes represent proteins that correspond to genes in one transcriptome cluster, whereas the green nodes represent proteins that correspond to genes belonging to a different cluster. The existence of two stable complexes can be hypothesized based on the integrated data. (b) The genes NTH1 and YLR270W have similar expression profiles (upper panel). Red indicates upregulation and green indicates downregulation. mRNA expressions of both genes are upregulated during heat shock and other forms of stress. Deletions of NTH1 and YLR270W each confer similar heat-shock sensitive phenotypes (lower panel). Integrating heterogeneous but related observations How are the data related? What kind of model? What kind of inferencing? Is the data validated? Can we take a “best guess” on how it might work by drawing upon other motifs or systems with similar properties? Problems? How is static data interpreted since it’s a dynamic system? How do we deal with low-resolution quality? How do we treat missing data? How do we deal with heterogeneous data types? How can we identify and evaluate competing hypotheses inferred by any system? Yes… SB is springing out of existing efforts anyway • E-cell (Keio University, Japan) • BioSpice Project (Arkin, Berkeley) • Metabolic Engineering Working Group (Palsson & Church, UCSD, Harvard) • Silicon Cell Project (Netherlands) • Virtual Cell Project (UConn) • Gene Network Sciences Inc. (Cornell) • Project CyberCell (Edmonton/Calgary) So where do we start? • Quantitative analysis of components and dynamics of complex biological systems Static (Tier 1) Deterministic (Tier 2) Stochastic (Tier 3) Features of complex systems • Nonlinearity global properties not simple sum of parts Features of complex systems • Feedback loops Features of complex systems • Open systems (dissipation of energy) Flagella uses energy: Features of complex systems • Can have memory (response history dependent) New protein may remain in cell after initial response, shifting the rate of reaction the next time the cell is exposed to a chemical Response Chemical concentration Features of complex systems • Nested (modules have complexity) Features of complex systems • There are no precise boundaries So where do we start? • Quantitatively account for these properties Static (Tier 1) – Different levels of modeling • Three tiers Deterministic (Tier 2) – Static interactions – Deterministic – Stochastic • Principles which transcend tiers… Stochastic (Tier 3) Principle 1: Modularity • Module – Interacting nodes w/ common function – Constrained pleiotropy – Feedback loops, oscillators, amplifiers Principle 2: Recurring circuit elements • Network motifs – Common methods to achieve an effect Principle 3: Robustness • Robustness – Insensitivity to parameter variation • Severe constraints on design – Robustness not present in most designs Aims of systems biology • Tier 1: Interactome – Which molecules talk to each other in networks? • Tier 2: Deterministic – What is the average case behavior? • Tier 3: Stochastic – What is the variance of the system? Aims of systems biology • Tier 1 – Get parts list Aims of systems biology • Tier 2 & 3 – Enumerate biochemistry – Define network/mathematical relationships – Compute numerical solutions Aims of systems biology • Tier 2 & 3 – Deterministic: Behavior of system with respect to time is predicted with certainty given initial conditions – Stochastic: Dynamics cannot be predicted with certainty given initial conditions Aims of systems biology • Deterministic – Ordinary differential equations (ODE’s) • Concentration as a function of time only – Partial differential equations (PDE’s) • Concentration as a function of space and time • Stochastic – Stochastic update equations • Molecule numbers as random variables • functions of time Y = # molecules at time t Tier 1: Static interactome analysis • Protein-protein – Signal transduction – Cell cycle • Protein-DNA – Gene regulation • Metabolic pathways – Respiration – cAMP Tier 1: Static interactome analysis • Goals – Determine network topology – Network statistics – Analyze modular structure Tier 1: Static interactome analysis • Limitations: – Time, space, population average – Crude interactions typical interactome • strength • types – Global features • starting point for Tier 2 & 3 first time-varying yeast interactome (Bork 2005) Tier 1: Static interactome analysis • Analysis methods – Functional Genomics • expression analysis • network integration – Graph Theory • scale free • small world Tier 2: Deterministic Models • Goal – model mesoscale system – average case behavior lumped cell • Three levels – ODE system – ODE compartment system – PDE – data limited… cell compartments continuous time & space (MinCDE oscillation) Tier 2: Deterministic Modeling • Results – Robust Chemotaxis (Barkai 1997) – MinCDE Oscillation (Howard 2003) – Feedback in Signal Transduction (Brandman 2005) • Output – time series plots (ODE) – condition on parameter values Brandman 2005 Tier 2: Deterministic Modeling • Example – Robustness in bacterial chemotaxis • Bacterial chemotaxis robust to parameter fluctuations! – Chemotaxis: bacterial migration towards/away from chemicals – Parameters • concentrations • binding affinities Tier 2: Deterministic Modeling • Bacterial chemotaxis – model as random walk • Exact adaptation – change in concentration of chemical stimulant – rapid change in bacterial tumbling frequency… – then adapts back precisely to its prestimulus value!! Random walk Experimental Design • Is exact adaptation robust to substantial variations in biochemical parameters? • Systematically varied concentrations of chemotaxis-network proteins and measured resulting behavior Distinguish between robust-adaptation and fine-tuned models of chemotaxis Tumbling frequency IPTG inducer pUA4 pUA4 E. Coli cheR -/- population pUA4 Adaption time pUA4 Express CheR over a 100-fold range Adaption precision 1 mM L-aspartate Adaptation precision = ratio of steady-state tumbling frequency of unstimulated to stimulated cells Summary of results Tumbling frequency 0.3 ± 0.06 (20-fold) Adaption time 3 ± 1 (3-fold) Adaption precision 1.04 ± 0.07 Tumbling frequency as a function of time for wild-type cells Conclusions from study • Exact adaptation is maintained despite substantial varations in network-protein concentrations – Exact adaptation is a robust property – …but adaptation time and steadystate behavior are fine-tuned Tier 3: Stochastic analysis • Fluctuations in abundance of expressed molecules at the single-cell level – Leads to non-genetic individuality of isogenic population Tier 3: Stochastic Analysis • When stochasticity is negligible, use deterministic modeling… • Molecular “noise” is low: – System is large • molar quantities – Fast kinetics • reaction time negligible – Large cell volume • infinite boundary conditions Tier 3: Stochastic Analysis • Molecular “noise” is high: – System is small • finite molecule count matters – Slow kinetics • relative to movement time – Large cell volume • relative to molecule size • Need explicit stochastic modeling! Tier 3: Ensemble Noise • Transcriptional bursting – Leaky transcription – Slow transitions between chromatin states • Translational bursting – Low mRNA copy number Tier 3: Temporal Noise Canonical way of modeling molecular stochasticity Tier 3: Spatial Noise Finite number effect: translocation of molecules from the nucleus to the cytoplasm have a large effect on nuclear concentration Cytoplasm N = average molecular abundance η (coefficient of variation) = σ/N • Decrease in abundance results ina 1/√N scaling of the noise (η=1/√N) Nucleus Recap • Three tiers – Interactomes – Deterministic – Stochastic Static (Tier 1) • Principles which cross tiers – Modularity – Reuse – Robustness Deterministic (Tier 2) Stochastic (Tier 3) Major challenges and limitations • Measurement of chemical kinetics parameters and molecular concentrations in vivo – Differences between in vitro and in vivo data • Compartmental specific reactions Major challenges and limitations • Data is the limit!!! – Functional genomic data (Interactomes) – E. Coli chemotaxis (Leibler, deterministic/robustness) • Important – parameter estimation – feedback based estimation methods Sachs 2005 Software • Tier 1: Interactomes – Graphviz, Bioconductor, Cytoscape • Tier 2: Deterministic – Matlab (SBtoolbox), Mathematica (PathwayLab) • Tier 3: Stochastic – R, Stochsim Software • High-performance algorithms to solve systems of PDE’s – Virtual Cell • Automated parsing of networks into stochastic and deterministic regimes – H-GENESIS – STOCK Summary • Systems Biology can be done by breaking down each system into modules • Many problems remain unsolved in exactly how to do this, but independent efforts are being developed in most areas that may one day merge together For next time • Read supplemental material S9 • Homework #10 due