CG087__LECT3

advertisement

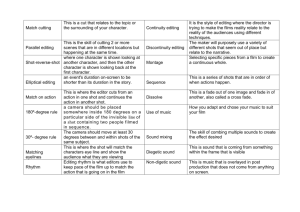

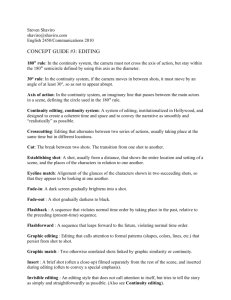

CG087. Time-based Multimedia Assets Week 9. Relationships Between Shots: Editing Today. Editing: the basics. 2. Dimensions of Editing 3. Continuity Editing 4. Discontinuity editing 5. Graphic relations 6. Rhythmic relations 7. Spatial relations 8. Temporal relations 9. Segments 10. Final Word. 1. Editing: the basics. Editing joins shots Shots are one or more frames recorded in continuous time and contiguous space There are various joins for Shots A and B Cut Fade-out Gradually lightens from black to Shot A Dissolve Gradually darkens end of Shot A to black Fade-in Shot A then Shot B Briefly superimpose end of Shot A on beginning of Shot B Wipe Shot B replaces Shot A by means of a boundary line moving across the screen Dimensions of Editing 1. Graphic relations between Shot A and Shot B 2. Rhythmic relations between Shot A and Shot B 3. Spatial relations between Shot A and Shot B 4. Temporal relations between Shot A and Shot B Graphic and Rhythmic Relations Graphic relations Editing together any two shots permits the interaction, through similarity and difference, of the purely pictorial qualities of these two shots Rhythmic relations Shot duration (long, short) Shot duration patterns (acceleration, deceleration) Spatial Relations Editing lets an omniscient range of knowledge become visible as omnipresence Editing permits any two points in space to be related through similarity, difference, or development Editing enables the construction of spaces Constructing Space Situate location of Shot B with establishing Shot A Construct illusion of spatial contiguity through joining of Shot A and Shot B (Kuleshov Effect context through editing not shot construction) Create physically impossible or ambiguous spaces Establish two dis-contiguous spaces through parallel editing (i.e., crosscutting) Temporal Relations Temporal order Flash-back Flash-forward Temporal duration Temporal ellipsis Temporal expansion Temporal frequency Shot repetition Temporal Duration Temporal ellipsis Punctuation Empty frames Dissolve, wipe, fade Shot A (character exits frame, then empty frame) Shot B (empty frame, then character enters frame) Cutaway Temporal expansion Overlapping editing Continuity Editing Graphic continuity Smoothly continuous from shot to shot Figures are balanced and symmetrically composed in frame Overall lighting tonality remains constant Action occupies central zone of the frame Rhythmic continuity Dependent on camera distance of the shot Long shots last longer than medium shots that last longer than close-up shots Spatial Continuity Editing 180 degree rule Ensures that relative positions in the frame remain consistent Ensures consistent eyelines (i.e., gaze vectors) Ensures consistent screen direction (i.e., direction of character movement within the frame) Use of 180 Degree Rule Establishing shot to establish axis of action Sequence of shot/reverse shots Focuses our attention on character reactions Eye-line match reinforces spatial continuity (Kuleshov Effect see later) Match on action reinforces spatial continuity Following 180 degree rule allows “cheat cuts” Continuity of action can override violations of 180 degree rule Temporal Continuity Editing Temporal order Forwardly sequential except for occasional use of flashbacks signaled by a dissolve or cut Temporal duration (seldom expanded) Usually in a scene plot duration equals story duration Punctuation (dissolves, wipes, fades), empty frames, and cutaways can elide time in shot and scene transitions Montage sequences can compress time Continuity editing Hollywood, narrative style analytic editing “invisible” shot transitions shots subordinated to unity of segment implies passive spectator Editing refers to the linking of shots, one to another, and to building segments out of the linking of shots. The history of cinema has produced two fundamental approaches to editing: continuity editing and discontinuity editing. Continuity editing Continuity editing is characteristic of the Hollywood studio style. A segment is broken down into closer shots to direct the spectator's attention only to dramatically significant parts of the action. While breaking down an action into different shots, the transitions between shots are designed--both graphically and rhythmically--so that the audience does not notice them. Continuity editing is often referred to as "invisible" editing because it minimizes as much as possible the spectator's perception of the movement from one shot to the next. The objective of this style is to link shots into a smooth, seamless, transparent flow that gives the impression of a homogeneous and continuous space. Thus continuity editing subordinates the formal identity of each shot to the cause and effect logic of narrative. Shots become parts of an overall unity that we perceive as a scene, rather than as a chain of individual shots. Discontinuity editing Modernist and avant-garde films “Montage” style Foregrounds shot transitions Stresses formal integrity of each shot Implies active spectator Discontinuity editing is more characteristic of the European avantgardes of the 1920's. It is often called the "montage style." It has traditionally been the basis for defining modernist film-making. As opposed to Hollywood editing, discontinuity editing emphasizes the formal identity and integrity of each shot. Thus the montage style tries to maximize the spectator's awareness of the formal properties of each shot. And, just as importantly, it tries to make apparent, even disjunctive, the movement from one shot to the next. Here cutting is conceived as a collision between shots, rather than the development of a linear chain where the parts (the shots) are incorporated into the impression of a unified whole. Continuity and discontinuity styles can exist together in a single film. Hollywood cinema has always made use of "montage scenes," for example. Obviously, many action and horror films use shock cuts to surprise and unnerve the audience. Editing also brings us back to segmentation, formal patterning of shots within segments. the linking of shots within segments, and segments in the film overall. Knowing how important because: Most narrative films are organized through large formal units; that is, their primary level of action and sense is that of the segment rather than the shot. Our understanding of the sense of a film does not simply rest at the level of the image, but through the association and juxtaposition of images--the assembly of shots into a segment, and of a number of segments into a film, all of which may be linked by fades, dissolves, wipes, or hard cuts. that is, understanding the For editing refers both to the linking of scenes or to recognize segments is Recap : The aesthetics of editing relies on four basic areas of choice and control graphic relations rhythmic relations spatial relations temporal relations Graphic relations. Factors of composition, framing, and editing come together to establish graphic relations between shots. Graphic relations are defined by purely pictorial qualities of the image, including: line, volume or shape, depth, angle, tonal contrast (light and dark), as well as the speed and direction of movement. When a graphic similarity carries over from the tail of one shot to the head of the next, we say that a match cut has occurred. The continuity style of editing relies heavily on match cutting to establish a smooth flow of narrative actions. Graphic relations LINE SHAPE DEPTH ANGLE TONAL CONTRAST SPEED/DIRECTION OF MOVEMENT Rhythmic relations Rhythmic relations. Exploiting pictorial discontinuities between shots is a powerful technique of both narrative and avant-garde cinema. Obviously, editing is also a way of controlling the rhythm or pacing of a film. The film-strip is a literal measure of time. Each frame is a spatial unit equivalent to 1/24th of a second. Therefore, the length of a strip of film determines the duration of the shot on the screen. For example, since the days of D. W. Griffith, chase scenes and suspense cutting have accelerated the rhythm of the film by systematically shortening the shots, thereby accelerating the flow of images towards a climax. Rhythm and pacing are thus the most visceral ways of involving an audience in the action. Spatial relations The Kuleshov effect And “Creative Geography” Lev Kuleshov Spatial relations. Lev Kuleshov--a Soviet filmmaker and teacher working in the wake of the October Revolution of 1917--formulated this idea though a bet with the famous Russian actor Mozshukin of the Moscow Art Theater. By juxtaposing the same passive image of the actor’s face with a plate of soup, then with a young women, and finally a child’s coffin, Kuleshov showed that the audience would interpret the actor’s “emotions” differently--as hunger, lust, and sadness. The sense and emotional tone of the segment was conveyed not through the actor's expression, but through a series of associations in the spectator's mind built through the juxtaposition of disparate shots. In short, meaning is constructed through the context established by editing. This phenomenon is now referred to as "the Kuleshov effect." "L.V. Kuleshov assembled in the year 1920 the following scenes as an experiment: 1. A young man walks from left to right. 2. A woman walks from right to left. 3. They meet and shake hands. The young man points. 3. A large white building is shown, with a broad flight of steps. 4. The two ascend the steps. The pieces, separately shot, were assembled in the order given and projected upon the screen. The spectator was presented with the pieces thus joined as one clear, uninterrupted action: a meeting of two young people, an invitation to a nearby house, and an entry into it. Every single piece, however, had been shot in a different place; for example, the young man near the G.U.M. building, the woman near Gogol's monument, the handshake near the Bolshoi Theater, the white house came out of an American picture (it was, in fact, the White House), and the ascent of the steps was made at St Saviour's Cathedral. What happened as a result? Though the shooting had been done in varied locations, the spectator perceived the scene as a whole.... There resulted what Kuleshov termed "creative geography." By the process of junction of pieces of celluloid appeared a new, filmic space without existence in reality. Buildings separated by a distance of thousands of miles were concentrated to a space that [appeared to ] be covered by a few paces of the actors" Temporal relations Editing controls fundamentally our understanding of narrative time as well as space. Through editing, the duration of actions and events can be expanded or contracted. Overlapping edits :can extend or repeat an action for dramatic emphasis. Jump-cuts: may be used to interrupt the space and time of a shot with distinct ellipses. Flashbacks and forwards: sense of history and prediction Segments Different types of segments can also be recognized through their different manipulations of space and time; that is, in how they specifically give form to the plot of the film in relation to the spectator's understanding of the story. We can learn to identify some conventional patterns of editing by thinking about how different types of film segments creative manipulate factors of space and time. In narrative cinema, there are three basic patterns: Segments defined by principles of contiguity or succession in space and time. Transitional segments where shots are linked in succession, but with emphatic ellipses in space and time. Segments defined by alternation, or the systematic repetition of two or more narrative actions. Types of narrative segments There are three basic kinds of narrative segments defined by succession or contiguity in space and time: 1. A sequence-shot describes the action of a scene in one long take without editing. It is actually a type of scene rather than a sequence. 2. A scene gives a strong impression of spatial and temporal continuity, and of unity of place and action, similar to a scene in the theater. The shots and actions are arranged in a strict relation of succession and contiguity, that is, the time of the plot is equivalent to the time of the story without any noticeable gaps in space or time. 3. A sequence differs from a scene in that the plot time and space contains minor or major gaps and ellipses to eliminate non-essential actions or events. Types of narrative segments Transitional segments are usually very brief. They are used to establish location or to indicate the elapse of time. The function of these segments is to provide a spatial or temporal transition in the plot of the film. thus informing the spectator that there is a gap or ellipsis in the story. There are generally two types of transitional segments: Descriptive sequences (including “montage” sequences ) establish a change in narrative place and time with a brief series of shots, often linked by dissolves. Episodic sequences condense lengthy story actions into a brief plot time by using dissolves or other marks of punctuation indicate ellipses of time. Types of narrative segments Another form of patterning story at the level of plot is parallelism, that is, a pattern or structure in which two or more narrative motifs or events are compared in order to demonstrate how they are alike or how they are different. Here there are four basic types. Alternating sequences systematically intertwines actions or motifs occurring within the same diegetic space. Parallel sequences (“cross-cutting”): from different diegetic spaces. flashbacks and flashforwards: cross-cutting that forms associations between different diegetic times as well as locales; there are temporal displacements either from present to past or present to future. metaphorical or associational montage: diegetically unrelated motifs are cut together to establish a conceptual or poetic relation. intertwines actions or motifs Final word It is important not to think of relations between shots as isolated phenomena. Temporal, rhythmic, graphic, and spatial relations may interact in both simple and complex ways in any given segment. Therefore, you should always try to comprehend how these four sets of choices for linking shots are organized into patterns across shots, as well as across segments .