1. What's the good of science?

advertisement

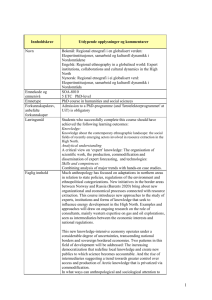

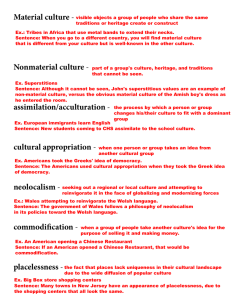

The present university and its future Hans Radder H.Radder@vu.nl 1. What’s the good of science? The problem 2. What’s the good of science? The philosophy of science approach 3. What’s the good of university science? A philosophical analysis of its current social legitimations 4. What’s the good of university science? Elements of an alternative vision 2 1. What’s the good of science? The problem Science: in the European sense (wetenschap or Wissenschaft); hence, it includes the humanities (or ‘human sciences’) The question “What’s the good of science?” asks for the aim or aims of science. My approach, in this presentation: Discuss the question of the aim or aims by looking at the answers to the question of the value of science, and address answers given from various philosophical and social perspectives. 3 2. What’s the good of science? The philosophy of science approach Some proposed aims: ● finding truth; ● finding the truth of statemens about the observable world; ● finding deep, theoretical explanations of observable phenomena; ● solving empirical and conceptual problems. Most philosophy of science is internalist ● limited to the content of the knowledge and methods of the (basic) scientists themselves. ● no, or little, attention is given to the socio-cultural embedding of the sciences. 4 3. What’s the good of university science? A philosophical analysis of its social legitimations Three characteristics of the current universities 3.1 Hierarchization The university is an ordinary enterprise. Efficiency is, or should be, one of its prime values. Therefore, university governance should be top-down, hierarchical. Consequence: ever fewer people have a voice in how universities are organized and in the nature of the scientific and administrative work done at these institutions. Conversely: an ever decreasing say by skilled professionals at the shopfloor. 5 3.2 Bureaucratization Two characteristics of bureaucratized universities: 1. Rise of a separate layer of administrators/managers and their support staff. Consequence: an ever widening gap between administrators and managers, on the one hand, and the shopfloor (from professors to secretaries and cleaners), on the other. 2. Formalization of the interactions between administrators/managers and the shopfloor. More specifically: a content-less view of the value of science. 6 Implication 1: content-less policies tend to erase important distinctions between disciplines. A large, or exclusive, valuing of journal publications, which is then imposed on humanities and social sciences. Can this preference be justified for the humanities and (a part of) the social sciences? No! Consider four journal issues in these disciplines: Total number of references (in 2012): 1079 References to books and book chapters: 527 (48,8%) (the philosophical journals: 55,9 %; the social science journals: 44,3 %) 7 Implication 2: content-less policies strongly value formal quality indicators, such as the journal impact factor (JIF) Definition JIF (for the year 2014): The average number of times articles from the 2012 and 2013 volumes have been cited in the year 2014. Two major problems: 1. the JIF merely measures the short-term ‘impact’, within one or two years after publication; it does not tell us much about the long-term significance of the articles. In addition, references to journal articles in books and book chapters are not taken into account. 2. The distribution of cited articles is strongly skewed: a few are highly cited, the rest far less or not at all. Implication: using the JIF in evaluating individual articles is strongly misleading. Yet, this happens very often. 8 3.3 Commodification (or economization) of science Academic commodification means that all kinds of scientific activities and their results are predominantly interpreted and assessed on the basis of economic (or financial) criteria. a. commodification includes, but is broader than, commercialization b. academic commodification is part of a comprehensive sociocultural development c. I leave out science outside of academia d. my focus is on academic research 9 Academic commodification: three central questions a. Which forms of commodification can be distinguished? -- contract research by a (commercial) external organization -- special professorships paid by commercial firms -- patenting practices of public universities -- hierarchical corporate structure of university administration -- prevalence of economic vocabularies and assessment procedures 10 Two examples 1. The role of brought-in (research) money ● is included in job contracts ● a top scientist = a top fund raiser ● is used in PR to explain the significance of a research project 2. Academic patenting practices (compared with open access). “NWO agrees that research results obtained with public money should be publically available as much as possible. … In this way, valuable knowledge can be used by researchers, companies and social organizations.” Why, then, does this not apply to patents, which are commercial monopolies? 11 b. How widespread and novel is the phenomenon of academic commodification? -- answers require detailed social-scientific and historical research -- differentiation between: forms of commodification, types of institutions, disciplines, countries, historical periods -- my conclusion: current academic commodification is a substantial and significant phenomenon 12 c. How to assess the commodification of academic research? -- the assessment may be philosophical, political or moral -- this requires a well-developed normative account of what we consider epistemically sound, socially legitimate and morally justified science -- answers may differ for distinct disciplines (medicine!) and for different forms of commodification (engineering sciences) 13 Negatively: avoid the pitfalls of the critique of academic commodification, such as: -- unjustly generalized personal experiences; -- lack of serious scholarship; -- inflated, inadequate accounts of science and academic institutions; -- rejection of requests for the social legitimization of science. 14 Positively: Use widely accepted codes of ethical conduct, not merely in assessing individual behavior, but rather in designing and implementing structural science policies. For instance: -- access to science should be open to any sufficiently talented person; -- results of public science should not be privately appropriated; -- scientists should not have a direct commercial interest in a specific outcome of their research; -- scientific claims should be critically scrutinized from different perspectives; Apply these norms to specific forms of commodified research, for example the patenting of the results of academic research. Conclusion concerning commodified academic science: it has many negative implications, partly epistemic, partly social and partly moral. 15 Overall conclusion current universities The hierarchization, bureaucratization and commodification of current universities is significant and problematic. It is a big mistake to see these as ‘merely the problems of some students at the University of Amsterdam’. See, among many other books and articles, Derek Bok, Universities in the marketplace (Princeton University Press, 2003) Hans Radder, ed., The commodification of academic research: science and the modern university (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010) Rudolf Dekker, Het excellentietraject: discussies over wetenschap, onderwijs en de universiteit (Panchaud, 2015) 16 4. What’s the good of university science? Elements of an alternative vision 4.1 From hierarchy to having a voice Having a voice and a vote: (permanent and temporary) scientists, students and support staff have the right to deliberate and decide on all matters that significantly affect them and about which they are knowledgeable. 4.2 From bureaucracy to substantive policy Especially this: a crucial role for debate and arguments, instead of topdown ukases and pompous rhetoric. 4.3 From commodification to public-interest science ● ‘Public interest’ has a normative component. ● ‘Public interest’ as a result of democratic debate. 17 Two important points concerning public-interest science: 1. The common definition of knowledge use (or “public interest”) goes in terms of ‘a target group’ and ‘the needs of its users’. However: another equally significant aspect of the social value of the humanities and social sciences is: the creation of novel accounts of our big questions, and of the (conceptual and normative) framework within which these questions can be legitimately phrased and discussed. Conclusion: a valid critique of the dominant notion of public interest is itself a legitimate form of public-interest science. 18 2. Two arguments for the public interest of basic research ● Basic research constitutes an indispensable knowledge resource for the purpose of coping with the novel and complex problems that will face us in the future. ● Teaching and learning basic research should include systematic reflection on the nature of science and its role in society. Under these conditions, it will provide society not only with expert researchers but also with critical and responsible citizens. 19