minimum

Review: In competitive markets, price adjusts to

“balance” supply and demand.

Markets are in equilibrium most of the time.

(We might regard this as a remarkable outcome if we didn’t understand the supply and demand model -remember, no one’s in charge!)

Some government policies are designed to interfere with the market process of price determination.

“Price controls”

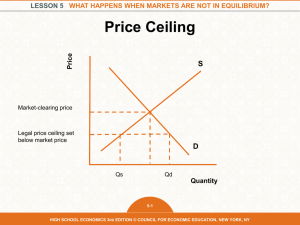

Price ceiling: A legal good can be sold.

maximum

on the price at which a

Price floor: A legal

minimum

good can be sold.

on the price at which a

Economists almost always oppose price controls:

They’re well-intentioned, but . . .

. . . they rarely help

all

who are supposed to benefit,

. . . and they often have unintended

bad

effects.

With a price ceiling, there are two possibilities: price p c1 p*

S

The price ceiling could be at or above p*. p* is a legal price and we would have equilibrium. (“Non-binding” price ceiling.) p c2

Q

S excess demand

Q

D

D

The price ceiling could be below p*. p* is illegal.

(“Binding” price ceiling.)

Price is p c2 and we have excess demand (“shortage”).

quantity

Price ceilings are intended to help buyers.

With a (binding) price ceiling, only some who want to buy at the ceiling price are able to buy.

Shortage creates problems:

Disappointed demanders have incentive to offer an illegally high price . . .

. . . so price ceilings are inherently hard to enforce.

Even if price ceiling can be

strictly

enforced, a “nonprice rationing mechanism” is needed.

Usually, price “rations” the available supply. Those willing to pay p* (or more) get to buy, others do not.

With a binding price ceiling, the usual price rationing mechanism is not allowed to work.

Non-price rationing mechanisms?

-- those willing to wait in line the longest get to buy.

-- only “friends” of suppliers get to buy.

Rent control: A binding price ceiling on the rental housing market.

($/ft.

2 / month)

S

SR p*

S

LR

Probably best to think of “quantity” as total square footage -- rather than number of apartments.

D

1

Q* (ft 2 /month)

Short-run supply

perfectly

inelastic?

In the (sufficiently) short run, number of aprtmts is fixed.

Rent control is often imposed in response to a big influx of population - increasing demand for rental housing.

Effects of such a demand shift - WITHOUT rent control:

($/ft.

2 / month) p** p*** p*

S

SR

In short-run:

Rent jumps to p**.

No quantity effect.

S

LR

D

1

D

2

Q* (ft 2 /month)

Q***

In long-run:

Rent comes down

(part-way) to p***.

Quantity increases to Q***.

Now consider the effects of the demand shift WITH rent control imposed at level of original equilibrium, p*:

($/ft.

2 / month)

S

SR excess demand

S

LR

In the short-run:

No increase in rent, but excess demand . . .

p*

D

2

D

1

. . . that persists throughout long-run.

Q* (ft 2 /month)

Rent control “cancels” the price signal that otherwise would have increased quantity of rental housing.

Rent control does deprive landlords of the short-run

“windfall” they otherwise get from increased demand.

Does it benefit tenants?

Some benefit -- those with rent-controlled apartments who are happy where they are.

Some lose -- those who make up “excess demand.”

Again: Excess demand isn’t relieved in long-run because rent control “cancels” the price signal.

(More on rent control: http://www.econlib.org/ . . .

)

Now price floors. As with price ceilings, there are two possibilities: price p f2

S

The price floor could be above p*. p* is illegal.

(“Binding” price floor.)

Price is p f2 and we have excess supply (“surplus”).

p* p f1 excess supply

Q

D

Q

S

D

The price floor could be at or below p*. p* is a legal price and we would have equilibrium. (“Non-binding” price floor.) quantity

The point of price floors is to benefit suppliers.

To accomplish this, government has to purchase surplus.

Agricultural commodity price support programs . . .

. . . for corn, for example.

What can the government do with the surplus?

Sell it?

Give it away?

Build more government corn bins!

Minimum wage: A price floor on the labor market.

Current federal minimum wage = $7.25/hr.

(as of 07/24/09)

Current Iowa minimum wage = $7.25/hr.

Current Illinois minimum wage = $8.25/hr.

Currently the highest state minimum wage = $8.67/hr.

(Washington)

(In San Francisco, minimum wage = $9.92/hr.)

(source: http://www.dol.gov/esa/minwage/america.htm#content )

Consider Iowa minimum wage of $7.25/hr.

In terms of annual income (assuming a work year of 50 weeks x 40 hrs./wk. = 2000 hrs.):

$7.25/hr x 2000 hrs./yr. = $14,500/yr.

U.S. Health and Human Services 2010 Poverty

Guideline:

Family of 4 = $22,050/yr.

( http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/10poverty.shtml

)

Market for (“low-skill”) labor: wage

($/hr.) w min w*

S

Note: In labor markets, firms are

“demanders,” households are

“suppliers.” surplus

D

L

D

L

S quantity of labor

(hrs.)

In this case, surplus = “unemployment” -- people who want to work at w min but cannot.

It’s supposed to benefit low-skill workers. Does it?

Some benefit -- those who keep their jobs when minimum wage goes into effect.

Some lose -- those who are displaced. (Employment falls (!) when law raises wage from w* to w min

.)

Are the benefits well-targeted? (Does it help mainly

“bread-winners” in low income households -- or mainly middle-class teenagers?)

(More on minimum wage: http://en.wikipedia.org . . .

)

How big is the “displaced worker” effect?

One recent study . . .

( http://www.theworkbuzz.com . . .

)

. . . says it’s “small.”

Economists are still somewhat divided on the minimum wage.