Rotational Motion & Moment of Inertia Lab - Online

advertisement

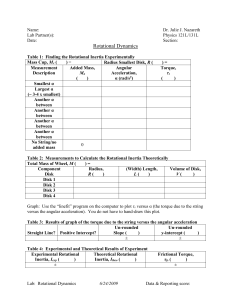

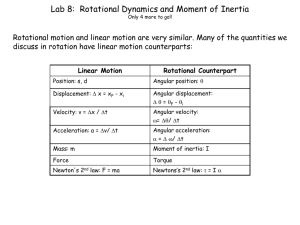

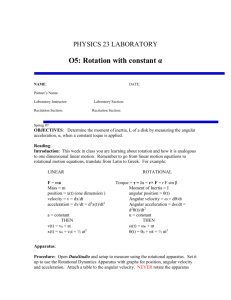

Lab 7: Rotational Motion and Moment of Inertia- Online version Objective The purpose of this experiment is to compare measured values of rotational inertia to values calculated using the theory below. Theory For rotational motion we need to redefine our variables that we used to discuss translational motion. For position, instead of x we use the angle (in radians). For velocity, instead of linear velocity v (m/s) we use angular velocity (rad/s) For acceleration, instead of linear acceleration a (m/s2) we use tangential angular acceleration (rad/s2). For a particle rotating at a distance r from the axis, we have the relationship between linear and angular variables as follows: x r ; v r ; a r . The DIRECTION is taken to be positive if the object is rotating counterclockwise, and negative if it is rotating clockwise. We also need to redefine our concepts of force and inertia. For translational motion we used Newton’s second law F=ma, where F was the force applied, m was the mass (inertia). The amount of linear acceleration depends directly on the force applied and inversely on the mass. For rotational motion we will use Torque () rather than force, and Moment of Inertia (I) rather than the mass. So our rotational version of Newton’s second law is I The torque is a measure of how much an applied force will cause an object to rotate, and depends on the size of the applied force, the distance from the axis that it is applied, and also the angle at which it is applied. The farther from the axis you applied the force (i.e. the bigger r), the easier it is to rotate the object. For example, we have all walked up to a glass door with a bar on it at some point in our lives, and pushed on the wrong end (by the hinge). If you do that, you have to push really hard to open the door. We always put the door knob at the farthest distance from the hinge as possible, to make it easy to open the door. Similarly, if you want to open a door, you push (or pull) perpendicular to the door to apply the greatest torque. If you pushed parallel to the door, there would be no rotation. So our equation for the torque is: Fr sin where is the angle between the force and the vector r from the axis to where the force is applied. For this lab we will always apply the force perpendicular to r, so our torque is just =Fr. The moment of inertia (I), is a measure of how difficult it is to make a certain object rotate. It depends on the mass of the object, and how far the mass is from the center of the object. In general, the farther the mass is from the axis, the harder it is to spin the object. (Try spinning your textbook about its corner instead of its center). For a particle of mass M at a distance R from the axis, I=MR2. If you have a continous object, like your textbook, which has a lot of different atoms all at different distances from the center, we need to integrate over the shape to get the moment of inertia. Your textbook has a table showing the moment of inertia for a bunch of different shapes. What we will do in this virtual lab is to apply a force to a disk by pulling on a string that is wound around the disk. We do this by hanging a mass from the end of the string and letting the mass drop. The applied force is then the TENSION in the string. The distance r, is the radius of the disk, (25cm). From these we can calculate the torque. This torque will cause the disk to rotate, and we will measure its acceleration. From this we can calculate the moment of inertia, I=and compare it to what it should be theoreticallyWe will then add masses to the top of the disk and repeat the experiment. Every mass we add will increase the moment of inertia by an amount I=MR2. Equipment This is the general setup of the experiment that you will find online at: http://www.fisica.uniud.it/~deangeli/applets/Multimedia/ExplrSci/dswmedia/momofI.htm pulley mass hanger and weight m1 bar m2 spindle, radius r d~1 m floor In this experiment, a small mass is attached to a string which rotates a disk about its axis. By measuring the acceleration of the small mass, the moment of inertia of the disk can be determined. The radius, r, of the disk and the spindle are both 0.25m for the online experiment. Procedure 1. Go to http://www.fisica.uniud.it/~deangeli/applets/Multimedia/ExplrSci/dswmedia/momofI.htm 2. On the right side of the screen choose the blue 100g weight and drag it up to the holder. 3. Hit the “Release” button, and watch the disk on the left side of the screen rotate as the mass descends. When the mass has reached the bottom, its acceleration will appear on the right side of the screen. Record this value in table 1. When you do this experiment in the lab, you will measur the time, t, for the weight to drop a distance, d, and calculate a=2d/t2. 4. Using your value for a, calculate the torque with error. The force which causes the torque is the tension in the string, FT = m(g-a), where m is the total mass on the mass hanger. Record both FT and Frin Table 1. The radius r, of the disk in this example is 25cm. Be sure to convert all quantities to standard SI units of kilograms and meters! 5. Calculate the angular acceleration (=a/r). Use the torque and the angular acceleration to calculate the moment of inertia of the disk. I, so I=. Call this value IA, the moment of inertia of the rotational apparatus. Compare it to the value of IA,calc = 0.3 kgm2 which we calculated for you based on the mass and radius of the disk. 6. Trial 2: Hit the “Go again” button, which will restore the hanger to the top. At this stage you will see 8 yellow “hot-spots” appear on the disk at the left. Four of these are at a distance of r/2=12.5cm from the axis, and four are at a distance of r from the center. Drag two red 250g balls to the disk, placing them at R=r/2, directly opposite from each other as shown below. Calculate the theoretical moment of inertia, I2,calc, of the two point masses about the axis of rotation using the appropriate formula from the theory section. I2,calc= m1R12+m2R22 Trial 2 layout: 7. Now repeat steps 1-5. The moment of inertia that you find in 5 is now the total moment of inertia, IA+I2,meas. Subtract the moment of inertia of the top of the apparatus, IA, as previously measured, to get the moment of inertia of the weights only, I2, meas. Compare your result with the calculated value of the moment of inertia of the weights (find percentage difference). 8. Trial 3. Repeat steps 6+7 with the two masses at the outside of the disk, i.e. at R=25cm. Call this I3,meas. Trial 3 layout: 9. Trial 4. Repeat steps 6+7 with four 250g masses: two masses at the outside of the disk, and two halfway along, all in a line. Call this I4,meas. (Now I4,calc will have 4 terms in it, one for each mass) Trial 4 layout: 10. Trial 5. Repeat steps 6+7 with four 250g masses: two masses at the outside of the disk, and two halfway along, at right angles to each other as shown. Call this I5,meas. Trial 5 layout: Data Table 1: Measurements of Moment of Inertia Trial # a(m/s2) FT(N) (rad/s2) m(g-a) a/r 1(apparatus only) rFT (Nm) Imeas (kgm2) 2 (masses at 12.5 cm) 3 (masses at 25 cm) 4 (masses at 12.5 and 25 cm inline) 5 (masses at 12.5 and 25 cm at 90°) Question 1. Are the moments of inertia in trial 4 and 5 the same? If so, why? Icalc (kgm2) 0.03 % diff