Price

advertisement

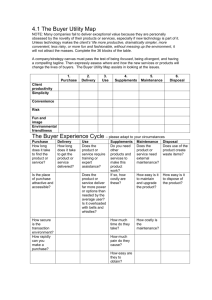

Team 2: Caitlin Clark Stephen Massimi Will Mayrath Katie Trevino Matt Vatankhah Get the Strategic Sequence Right The next challenge of a blue ocean strategy is to build a robust business model 4th Principle of blue ocean strategy: Get the strategic sequence right Fleshing out and validating blue ocean ideas to ensure commercial validity With the right strategic sequence, you can dramatically reduce business model risk The Right Strategic Sequence Need to build blue ocean strategy in the sequence of buyer utility, price, cost, and adoption Buyer utility is the starting point ○ If there is no buyer utility, there is no potential for blue ocean to begin with The first two steps address the revenue side The cost side ensures that a company creates a leap in value for itself in the form of profit Adoption: the blue ocean strategy is complete only when you address adoption hurdles to ensure the success of your idea Buyer Utility Is there exceptional buyer utility in your business idea? No—Rethink Yes Price Is your price easily accessible to the mass of buyers? The Right Strategic Sequence, continued Yes Cost Can you attain your cost target to profit at your strategic price? No—Rethink Yes Adoption What are the adoption hurdles in actualizing your business idea? Are you addressing them up front? Figure 6-1 (page 118) No—Rethink Yes A Commercially Viable Blue Ocean Idea No—Rethink Test for Exceptional Utility Example: Philips’ CD-i Value innovation is not the same as technology innovation To get around this, create a strategic profile that passes the initial litmus test of being focused, being divergent, and having a compelling tagline that speaks to buyers The buyer utility map helps managers look at this issue from the right perspective Outlines all the levers companies need to pull to deliver exceptional utility to buyers as well as various experiences buyers can have with the product or service Test for Exceptional Utility, continued—Figure 6-2 (page 121) The Six Utility Levers Customer Productivity Simplicity Convenience Risk Fun and Image Environmental Friendliness The Six Stages of the Buyer Experience Cycle 4. 5. 6. Supplements Maintenance Disposal 1. Purchase 2. Delivery 3. Use The Six Stages of the Buyer Experience Model A buyer’s experience can usually be broken down into six stages, running more or less sequentially from purchase to disposal At each stage, managers can ask a set of questions to gauge the quality of buyers’ experiences The Six Stages of the Buyer Experience Model, continued Figure 6-3 (page 123) Purchase—How long does it take to find the product you need? Delivery—How long does it take to get the product delivered? Use—Does the product require training or expert assistance? Supplements—Do you need other products or services to make this product work? Maintenance—Does the product require external maintenance? Disposal—Does use of the product create waste items? The Six Utility Levers Cutting across the stages of the buyer’s experience are what we call utility levers The way in which companies can unlock exceptional utility for buyers The most commonly used lever is customer productivity, in which an offering helps a customer do things faster and better The greatest blocks to utility often represent the greatest and most pressing opportunities to unlock exceptional value Using the buyer utility map, you can clearly see how, and whether, a new idea removes the biggest blocks in converting noncustomers into customers The Six Utility Levers, continued— Figure 6-4 (page 124) Purchase Delivery Use Supplements Maintenance Disposal Customer Productivity: In which stage are the biggest blocks to customer productivity? Simplicity: In which stage are the biggest blocks to simplicity? Convenience: In which stage are the biggest blocks to convenience? Risk: In which stage are the biggest blocks to risk? Fun and image: In which stage are the biggest blocks to fun and image? Environmental Friendliness: In which stage are the biggest blocks to environmental friendliness? The Six Utility Levers, continued Example: Ford Model T The buyer utility map highlights the differences between ideas that genuinely create new and exceptional utility, and those that are essentially revisions from existing offerings The aim is to check whether your offering passes the exceptional utility test From Exceptional Utility to Strategic Pricing To secure a strong revenue stream for your offering, you must set the right strategic price It is very important to know from the start what price will capture buyers Companies are implementing this strategy because: Volume generates higher returns than it used to ○ Companies bear more costs in product development than in manufacturing ○ Example: Software Industry To a buyer, the value of a product or service may be closely tied to the total number of people using it ○ Network Externalities—you sell millions or you sell nothing at all From Exceptional Utility to Strategic Pricing, continued Free Riding The rise of knowledge-intensive products creates the potential for free riding Relates to the non-rival and partially excludable nature of knowledge Rival Good One firm precludes its use by another Example: IBM Non-rival Good One firm does not limit its use by another Example: Virgin Atlantic Airways Excludability A good is excludable if the company can prevent others from using it because of limited access or patent protection Enforces the risk of free riding Example: Intel, Curves From Exceptional Utility to Strategic Pricing, continued All this means is companies must set a strategic price to attract buyers and also retain them Given the high risk for free riding, companies must set a strategic price from day one Strategic pricing addresses one question: Is your offering priced to attract the mass of target buyers from the start so that they have a compelling ability to pay for it? Price Corridor of the Mass—Figure 65 (page 128) Step 1: Identify the price corridor of the mass. Three alternative product/service types: Different form Same Different form, and function, Form same function same objective Step 2: Specify a price level within the price corridor. High degree of legal and resource protection Difficult to imitate Price Corridor of the Mass Mid-level pricing Some degree of legal and resource protection Low degree of legal and resource protection Easy to imitate Size of circle is proportional to number of buyers that Price Corridor of the Mass, continued Step 1: Identify the Price Corridor of the Mass Main challenge is to understand the price sensitivities of those people who will be comparing the new product or service with the host of very different-looking products and services offered outside the traditional competitors Different Form, Same Function—a product or service that performs the same function but takes a different form – Example: Ford’s Model T Price Corridor of the Mass, continued • Step 1: Identify the Price Corridor of the Mass, continued – Different Form and Function, Same Objective—a product or service takes a different form and serves a different function but has the same objective – Example: Cirque du Soleil – Managers should then list the groups of alternative products and services, and graphically plot the price and volume of these alternatives – The price bandwidth that captures the largest groups of target buyers is the price corridor of the mass Price Corridor of the Mass, continued Step 2: Specify a Level Within the Price Corridor Helps managers determine how high a price they can afford to set within the corridor without inviting competition from imitation products or services Two factors ○ Degree to which the product or service is legally protected ○ Degree to which the company owns some exclusive asset or core capability Price Corridor of the Mass, continued Upper-Boundary Strategic Pricing—are protected legally and have an exclusive asset or core capability Companies should pursue mid-to-lower Boundaries if any of the following apply: Their blue ocean offering has high fixed costs and marginal variable costs Their attractiveness depends heavily on network externalities Their cost structure benefits from steep economies of scale and cope; volume brings significant cost advantages From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing To maximize profit potential, a company should start with the strategic price and then deduct its desired profit margin from the price to arrive at the target cost Will make it difficult for potential followers to match as well as be profitable Company must reduce costs to get to cost target ○ Cirque du Soleil saved by eliminating animals and stars ○ Ford made Model T in one color with very few options From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued Sometimes, these cost reductions are not enough to hit the cost target Ford introduced the assembly line ○ Replaced expensive skilled craftsmen with less expensive unskilled laborers ○ Reduced labor hours by 60% From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued To hit cost target, companies have three principal levers that they can pull: 1. Streamlining operations and introducing cost innovations from manufacturing to distribution 2. Partnering 3. Changing the pricing model of the industry From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued Lever 1: Streamlining operations and introducing cost innovations Can raw materials be replaced by unconventional, less expensive ones? ○ Switching from metal to plastic Can your physical location be moved from prime real estate to lower-cost locations? ○ Home Depot, IKEA, Wal-Mart ○ Southwest Airlines is doing business at secondary airports Love Field, not DFW From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued Lever 1: Streamlining operations and introducing cost innovations, continued Swatch Example ○ By using this lever, Swatch was able to arrive at a cost structure 30% lower than any other watch company in the world ○ Was able to sell “cheap” watches at $40 as opposed to the $75 other watch companies were charging This low price left no profit margin for Japanese or Hong Kong-based companies to copy Swatch and undercut its price From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued Lever 1: Streamlining operations and introducing cost innovations, continued Swatch Example: How did they do it? ○ Knowing the price in which the watch would be sold, the Swatch project team worked backwards to arrive at the target cost Involved determining the margin needed to support marketing and services and earn a profit ○ Because of high cost of Swiss labor, radical changes in the product and production methods were needed to achieve the target cost of $40 Used plastic instead of metal or leather Reduced the number of inner parts from 150 to 51 Developed new and cheaper assembly techniques - Used ultrasonic welding instead of screws to seal the watch cases From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued Lever 1: Streamlining operations and introducing cost innovations, continued Swatch Example, continued ○ Changes enabled Swatch to reduce direct labor costs from 30% to 10% of total costs ○ Because of these changes, Swatch was able to profitably dominate the mass market for watches Previously dominated by Asian manufacturers with access to cheaper labor From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued Level 2: Partnering Many companies mistakenly try to carry out all the production and distribution activities themselves Partnering provides needed capabilities fast and effectively at a much lower cost It allows a company to use other companies’ expertise and economies of scale From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued Lever 2: Partnering, continued IKEA Example ○ IKEA achieves the lowest prices possible on their some 20,000 products by partnering with around 1,500 companies, getting the lowest prices for materials and production SAP Example ○ German-based business application software maker, SAP, partnered with Capgemini and Accenture, two leading consulting firms, as well as Oracle Capgemini and Accenture afforded SAP a global sales force overnight at no extra cost Oracle afforded SAP a world-class central database, while saving them hundreds of millions of dollars in development costs From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued Lever 3: Changing the pricing model of the industry When videos first came out, they were being sold for around $80 ○ The strategic price of a video had to be set in relation to going to movies, not to owning a tape for life Companies could not make money by selling the videos for a few dollars Blockbuster changed the pricing model from selling to renting ○ Allowed them to strategically price videos at a few dollars per rental ○ They made more money by repeatedly renting out the $80 videos than they would have by selling them alone From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued Lever 3: Changing the pricing model of the industry, continued Companies have used several innovations in pricing models to profitably deliver on the strategic price ○ Time-shares NetJets follows this model by selling the use of a jet for a certain amount of time to corporate customers as opposed to just selling the jet ○ Slice-shares Mutual fund managers follow this model by bringing highquality portfolio services to small investors by selling a sliver of the portfolio instead of the whole portfolio ○ Equity interest in the customer’s business Hewlett-Packard has traded high-powered servers to Silicon Valley start-ups for a share of their revenues - Customers get much needed servers, while HP gets the opportunity to make much more than the price of the servers From Strategic Pricing to Target Costing, continued—Figure 6-6 (page 136) The Strategic Price The Target Profit The Target Cost Streamlining and Cost Innovations Pricing Innovation Partnering 1. A company begins with its strategic price 2. Deduct target profit margin to arrive at target cost 3. To hit the cost target that supports that profit, there are 2 key levers • Streamlining and cost innovations • Partnering 4. When the target cost cannot be met despite all efforts to build a low-cost business model, turn to the third lever, Pricing innovation • Even when target cost can be met, pricing innovation can be pursued From Utility, Price, and Cost to Adoption Almost by definition, an unbeatable business model threatens the status quo, and thus may provoke fear and resistance among a company’s three main stakeholders: its employees, its business partners, and the general public The company must first overcome such fears by educating the fearful From Utility, Price, and Cost to Adoption, continued Employees Failure to adequately address the concerns of employees about the impact of a new business idea on their livelihoods can be expensive Example: Merrill Lynch ○ When management announced plans to create an online brokerage service, reports of resistance and infighting within the brokerage division caused the stock price to fall 14% From Utility, Price, and Cost to Adoption, continued Employees, continued Before companies go public with an idea, they should make a concerted effort to communicate to employees that they are aware of the threats posed by the execution of the idea Example: Morgan Stanley Dean Witter & Co. ○ Engaged employees in open internal discussion of the company’s strategy for meeting the challenge of the Internet ○ The market realized that employees understood the need for an e-venture, and company shares rose 13% upon announcing the venture From Utility, Price, and Cost to Adoption, continued Business Partners Resistance of partners who fear that their revenue streams or market positions are threatened by a new business idea can potentially be very damaging Example: SAP ○ When developing the AcceleratedSAP (ASAP) product, active cooperation of large consulting firms was required These firms were deriving substantial income from lengthy implementations of SAP’s other products, and were thus not incentivized to find the fastest way to implement the ASAP software ○ SAP resolved this dilemma by openly discussing the issues with partners Executives convinced the consulting firms that they had more to gain by cooperating From Utility, Price, and Cost to Adoption, continued The General Public Opposition can also spread to the general public, with devastating effects, especially if the idea is very new and innovative, threatening established social or political norms Example: Monsanto ○ Intentions have been questioned by European consumers ○ Mistake: allowed others to take charge of the debate, rather than educating the public on the benefits of genetically modified food and its potential to eliminate world famine and disease From Utility, Price, and Cost to Adoption In educating these three groups of stakeholders, the key challenge is to engage in an open discussion about why the adoption of the new idea is necessary Need to explain its merits, set clear expectations for its ramifications, and describe how the company will address them Companies that take the trouble to have such a dialogue with stakeholders will find that it amply repays the time and effort involved The Blue Ocean Idea Index The Blue Ocean Idea (BOI) Index provides a simple but robust test to ensure commercial success of a company based on four criteria: Utility—Is there exceptional utility? Are there compelling reasons to buy your offering? Price—Is your price easily accessible to the mass of buyers? Cost—Does your cost structure meet the target cost? Adoption—Have you addressed adoption hurdles up front? The Blue Ocean Idea Index, continued—Figure 6-7 (page 140) Philips Motorol DoCoM CD-i a Iridium o imode Japan Utility Is there exceptional utility? Are there compelling reasons to buy your offering? - - + Price Is your price easily accessible to the mass of buyers? - - + Cost Does your cost structure meet the target cost? - - + - +/- + Adoptio Have you addressed adoption hurdles up n front? Had Philips’ CD-i and Motorola’s Iridium scored their ideas on the BOI Index, they would have seen how far they were from opening up lucrative blue oceans The Blue Ocean Idea Index, continued Where did they go wrong? Philips’ CD-i ○ Did not create buyer utility with its complex technological functions and limited software capabilities ○ Priced out of reach from mass of buyers along with costly manufacturing process ○ Took more than 30 minutes to explain to customers, leaving no incentive for sales clerks to sell CD-i in fast-moving retail Blue Ocean Idea Index, continued Where did they go wrong?, continued Motorola Iridium ○ Unreasonably expensive because of high production costs ○ Provided no attractive utility because of inability to be used in buildings or cars; also, being very large ○ Overcame many regulations and secured rights from numerous countries, but had a poor sales and marketing team Blue Ocean Idea Index, continued What did they do right? NTT DoCoMo i-mode ○ Ignored the technology race and price competition over voice-based wireless devices and instead brought the Internet to cell phones ○ Offered exceptional buyer utility with an affordable low price in the “nonreflection” strategic zone, encouraging impulse buying and reaching the masses quickly Blue Ocean Idea Index, continued • What did they do right?, continued – NTT DoCoMo i-mode, continued • Created a win-win partnership network by regularly sharing know-how and technology with its handset manufacturing partners to help them stay ahead of competition • Played the role of the gateway to the wireless network, expanding and updating the list of i-mode menu sites while attracting content providers to join the network Blue Ocean Idea Index, continued What did they do right?, continued NTT DoCoMo i-mode, continued ○ Instead of using the Wireless Markup Language (WML), they used c-HTML, an existing and already widely used programming language in Japan, making the i-mode more attractive to content providers because of ease of transition from PC web pages to imode web pages Blue Ocean Idea Index, continued NTT DoCoMo i-mode passed all four criteria of the BOI index, ensuring its substantial success Six months after its launch, subscribers had reached over 1 million Within two years, subscribers had reached 21.7 million From 1999 to 2003, revenue from the transmission of data, pictures, and text messages increased from 295 million yen ($2.6 million) to 886.3 billion yen ($8 billion) DoCoMo now exceeds its parent company, NTT, in terms of market capitalization as well as potential for profitable growth