Stories of Ourselves Either

advertisement

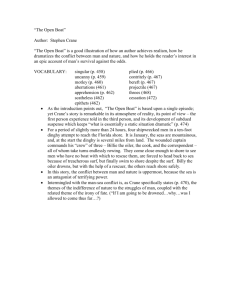

Stories of Ourselves Either (a) Discuss ways in which two stories present characters’ responses to tragedies. Or (b) Comment closely on ways the following passage presents the experience of living in wartime. The truck was full of dynamite, which any one of the many bullets fired could have set off at any moment – and it was near enough to us to have taken our shed clean away. My father and I kept our heads down, as the Germans by this time (early in ’44) were very nervous and shot at anything that moved, if they felt it threatened them. But I wanted to warn Cécile, who was due to pass at any minute. To run up the road would have attracted fire, and even to go the back way, through the vineyards, would have been assumed suspicious by the Germans. So I walked up the road. ‘Where the hell are you going?’ yelled my father. ‘For a walk,’ I called back, and then kept going, keeping by the verge, with my hands in my pockets, looking as ordinary as possible but with terror beating in my mouth. I had, I think, a fifty-fifty chance of attracting fire, but none came. When I saw Cécile, I waved, and she stopped. ‘You’re going to be late for work today,’ I said. She held my hand. She was quite startled to see me out of my usual place. She took the long, winding back route and arrived safely. My return was easier: the German guards, looking minuscule against the Latil, hardly seemed to look at me. There is nothing worse than facing danger with your spine. That evening (by which time everything had been cleared up), Cécile thanked me with an open kiss. My father called me ‘a bloody fool’ and gripped my hand. He was proud of me, for once. Then the village, one Sunday, was crossed with the darkest shadow of war – that of blood. We were sitting down to eat when the rumble of a convoy sounded. ‘Bloody Boche,’ murmured my father, followed by something ruder, in patois. A few minutes later there was shouting, and sounds of gunfire from the northern end of the village, near the little crossroads. There was lots of banging on doors, and we were all told to pay a visit to the Mairie. In the larger room, on the big table there used for the meetings of the Conseil Municipal, were laid three bodies. Their guts were literally looped and dripping almost to the floor, ripped open by that brief burst of gunfire. One of them was a local man, the son of the butcher, a little older than myself. The other two I did not know. They looked surprised in death, and it was said later that, though all three were members of the Maquis, no one knew why they had taken that road slap-bang into the German convoy, and then reversed in such panic. I know why: because, for all their bravery, they were mortals, and felt mortal fear. I was sick in the gutter, immediately afterwards, to my shame. We all – the whole village – filed past the bodies and came out silent and pale. A few of us cried. I had never seen anything like it before, the only dead person I had ever looked at being my poor mother, at peace in her bed. The following week they looped a rope around the long neck of Petit Ours, whom they’d caught in a botched raid on the gendarmerie, and pushed him from the town bridge – over which the schoolchildren were forced to walk class by class in the afternoon, while the body swayed in the wind. The Mayor had to give a speech, thanking the Boche for keeping public order and so forth. The atmosphere was terrible. It crept up the road and cast my father and I, and most of our clients, into a deep gloom. Tyres Stories of Ourselves Either (a) Discuss ways in which two stories present different kinds of bravery. Or (b) Comment closely on ways the following passage presents the disappointment of a fading relationship. Lying on the bed, I hold the cluster of grapes above my face, and bite one off as Romans do in films. Oh, to play, to play again, but my only playmate now is Lucy and she is out by the pool with her cousins. A few weeks ago, back in Cairo, Lucy looked up at the sky and said, ‘I can see the place where we’re going to be.’ ‘Where?’ I asked, as we drove through Gabalaya Street. ‘In heaven.’ ‘Oh!’ I said. ‘And what’s it like?’ ‘It’s a circle, Mama, and it has a chimney, and it will always be winter there.’ I reached over and patted her knee. ‘Thank you, darling,’ I said. Yes, I am sick – but not just for home. I am sick for a time, a time that was and that I can never have again. A lover I had and can never have again. I watched him vanish – well, not vanish, slip away, recede. He did not want to go. He did not go quietly. He asked me to hold him, but he couldn’t tell me how. A fairy godmother, robbed for an instant of our belief in her magic, turns into a sad old woman, her wand into a useless stick. I suppose I should have seen it coming. My foreignness, which had been so charming, began to irritate him. My inability to remember names, to follow the minutiae of politics, my struggles with his language, my need to be protected from the sun, the mosquitoes, the salads, the drinking water. He was back home, and he needed someone he could be at home with, at home. It took perhaps a year. His heart was broken in two, mine was simply broken. I never see my lover now. Sometimes, as he romps with Lucy on the beach, or bends over her grazed elbow, or sits across our long table from me at a dinner-party, I see a man I could yet fall in love with, and I turn away. I told him too about my first mirage, the one I saw on that long road to Maiduguri. And on the desert road to Alexandria the first summer, I saw it again. ‘It’s hard to believe it isn’t there when I can see it so clearly,’ I complained. ‘You only think you see it,’ he said. ‘Isn’t that the same thing?’ I asked. ‘My brain tells me there’s water there. Isn’t that enough?’ ‘Yes,’ he said, and shrugged. ‘If all you want to do is sit in the car and see it. But if you want to go and put your hands in it and drink, then it isn’t enough, surely?’ He gave me a sidelong glance and smiled. Soon, I should hear Lucy’s high, clear voice, chattering to her father as they walk hand in hand up the gravel drive to the back door. Behind them will come the heavy tread of Um Sabir. I will go out smiling to meet them and he will deliver a wet, sandy Lucy into my care, and ask if I’m OK with a slightly anxious look. I will take Lucy into my bathroom while he goes into his. Later, when the rest of the family have all drifted back and showered and changed, everyone will sit around the barbecue and eat and drink and talk politics and crack jokes of hopeless, helpless irony and laugh. I should take up embroidery and start on those Aubusson tapestries we all, at the moment, imagine will be necessary for Lucy’s trousseau. Yesterday when I had dressed her after the shower she examined herself intently in my mirror and asked for a french plait. I sat behind her at the dressing table blow-drying her black hair, brushing it and plaiting it. When Lucy was born Um Sabir covered all the mirrors. His sister said, ‘They say if a baby looks in the mirror she will see her own grave.’ We laughed but we did not remove the covers; they stayed in place till she was one. Sandpiper Stories of Ourselves Either (a) Discuss different ways in which two stories present individual characters who feel out of touch with the world around them. Or (b) Comment closely on the writing of the following passage, paying particular attention to the way the climax of the story is presented. He thought: ‘I am going to drown? Can it be possible? Can it be possible? Can it be possible?’ Perhaps an individual must consider his own death to be the final phenomenon of nature. But later a wave perhaps whirled him out of this small deadly current, for he found suddenly that he could again make progress toward the shore. Later still he was aware that the captain, clinging with one hand to the keel of the dinghy, had his face turned away from the shore and toward him, and was calling his name. ‘Come to the boat! Come to the boat!’ In his struggle to reach the captain and the boat, he reflected that when one gets properly wearied drowning must really be a comfortable arrangement – a cessation of hostilities accompanied by a large degree of relief; and he was glad of it, for the main thing in his mind for some moments had been horror of the temporary agony. He did not wish to be hurt. Presently he saw a man running along the shore. He was undressing with most remarkable speed. Coat, trousers, shirt, everything flew magically off him. ‘Come to the boat!’ called the captain. ‘All right, Captain.’ As the correspondent paddled, he saw the captain let himself down to bottom and leave the boat. Then the correspondent performed his one little marvel of the voyage. A large wave caught him and flung him with ease and supreme speed completely over the boat and far beyond it. It struck him even then as an event in gymnastics and a true miracle of the sea. An overturned boat in the surf is not a plaything to a swimming man. The correspondent arrived in water that reached only to his waist, but his condition did not enable him to stand for more than a moment. Each wave knocked him into a heap, and the undertow pulled at him. Then he saw the man who had been running and undressing, and undressing and running, come bounding into the water. He dragged ashore the cook, and then waded toward the captain; but the captain waved him away and sent him to the correspondent. He was naked – naked as a tree in winter; but a halo was about his head, and he shone like a saint. He gave a strong pull, and a long drag, and a bully heave at the correspondent’s hand. The correspondent, schooled in the minor formulae, said, ‘Thanks, old man.’ But suddenly the man cried, ‘What’s that?’ He pointed a swift finger. The correspondent said, ‘Go.’ In the shallows, face downward, lay the oiler. His forehead touched sand that was periodically, between each wave, clear of the sea. The correspondent did not know all that transpired afterward. When he achieved safe ground he fell, striking the sand with each particular part of his body. It was as if he had dropped from a roof, but the thud was grateful to him. It seems that instantly the beach was populated with men with blankets, clothes, and flasks, and women with coffeepots and all the remedies sacred to their minds. The welcome of the land to the men from the sea was warm and generous; but a still and dripping shape was carried slowly up the beach, and the land’s welcome for it could only be the different and sinister hospitality of the grave. When it came night, the white waves paced to and fro in the moonlight, and the wind brought the sound of the great sea’s voice to the men on the shore, and they felt that they could then be interpreters. The Open Boat