TNU - LONG LIFE AND HAPPINESS IN JAPAN'S SUNSHINE ISLES

advertisement

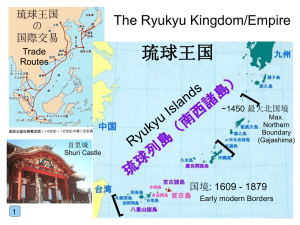

LONG LIFE AND HAPPINESS IN JAPAN'S SUNSHINE ISLES Okinawa is part of Japan, says Teresa Machan, but with the best bits of other Asian neighbours added in We were halfway to Coconut Moon, a beach bar owned by Kiyomasa Higa, Japan's godfather of rock, when the taxi radio crackled into action. Coconut Moon was shut, having conceded defeat to Typhoon Lupit. The locals had been praying for rain and they'd got it. Lupit, the first typhoon of the year, arrived in Okinawa about two hours after we did. But while typhoons have scant regard for tourists, our driver had it sussed. "You want awamori [a rice-based spirit]? Dancing?" After three days of lashing rain and cancelled flights and ferries our bedraggled crowd was up for anything. And that's how we ended up in Nakayuki (Little Break), an inconspicuous bar in the village of Onna, taking turns on a traditional threestringed guitar, eating dragon fruit, necking guava juice laced with awamori and "pushing the happiness" until 3am. Sharing the love with locals has never been so much fun. Welcome to Japan's sub-tropical alter ego. An island archipelago flung 1,000km across the Pacific, Okinawa is Japan, but not as we know it. Even the Japanese regard Okinawa as exotically foreign, and until its annexation to mainland Japan as Okinawa Prefecture in 1879, it was exactly that. The Ryukyu Kingdom was for centuries a self-governing tributary state to China, before being invaded by the mainland Satsuma clan at the start of the 17th century. The capital Naha, midway down the island chain on the main island, is closer to the tip of the Philippines than it is to Tokyo and on a clear day, from the southernmost island, Yonaguni, it's possible to see Taiwan, 111km away. If you're looking for quintessential Japan you won't find it here, but Okinawa's bizarre mish-mash of influences makes an interesting ride. Among its biggest draws are the people. A happy, welcoming if endearingly bonkers lot, the dark-skinned Okinawans are an origindefying blend of South Pacific-meets-North Asia, with a dash of the Inuit for good measure. The rare fusion of influences also permeates music, culture and dialect. Traditional music in Okinawa has overtones of gamelan from Indonesia. Its stir-fries are comfortingly familiar. Chinese "lucky" cats litter the streets, and Japan's clean architectural lines are hijacked by curlicued eves that infiltrate the roofs of temples, castles and traditional houses. Where mainland Japan is conservative, Okinawa is carefree and progressive. Tokyo's "salaryman" suits are replaced by kariyushi wear (the local version of the Hawaiian shirt). These days Okinawa is regarded as a quirky, relatively hip outpost of Japan. Cult-obsessed Japanese teenagers follow its underground music scene, and the annual Peaceful Love Festival draws fans from across Asia. Inspired in part by the popular Japanese soap Churasan, set on one of its sundrenched islands, six million other Japanese tourists come to fling a Hello Kitty beach towel across one of its hundreds of snow-white beaches, or to snorkel, dive and kayak around coral-fringed islands. A trip to one of these islands (around 50 out of 160 are populated) is rewarded with a rare glimpse into a sunny rural idyll. The shallow channel separating Iriomote and Yufujima is crossed by buffalo cart. Ishigaki and its offshoot islands are home to a rare breed of beef cattle, ranked up there with Kobe. On Kuroshima there are more cows than people. Miyakojima claims to have the best sea salt in the world – with 18 minerals, it's listed in the Guinness Book of Records. Whales migrate to the stunning Kerama Islands, 30km west of Naha, while croissant-shaped Minna, looped by snow-white sand, is a two-mile kayak paddle or a 15-minute ferry ride away. Other islands, like far-flung Miyako, explored by 30,000 divers a year, are best reached via a short flight. Okinawan cuisine is among the healthiest in the world, but a shaving of familiar pink stuff may find its way into your stir-fry. US forces, who fought in the Battle of Okinawa of 1945, linger on in controversially spacious bases scattered across the islands and in their sole culinary legacy – Spam. For all that Okinawa has borrowed from its neighbours, it has given the world a whole lot more – not least a model for longevity, and one of its most popular forms of martial art. This, after all, is the birthplace of Mr Miyagi, of Karate Kid fame. In Naha I paid a visit to Bunbukandojo, one of the numerous dojo (karate gyms) open to tourists. In the front yard I found the pint-sized, grey-bearded sensei Nakamoto Masahiro – a 10th-level black belt master, author of numerous books and one of the most revered karate sensei in the world – up a ladder, plucking bananas. There is only so much fruit one can consume in the name of politeness – even in Japan. Five bananas down the line, I was saved by the rain. Mr Nakamoto's protege ushered me into the drill hall, where he proceeded to demonstrate "the alphabet of karate moves". My favourite, the knife chop, would go down a treat on the mean streets of Tooting. Now and then Mr Nakamoto would tilt an elbow, or tweak a finger end, but the best was yet to come with the 71-year-old's demonstration of kobudo, a quick-fire, terrifyingly impressive martial art that uses weapons. In a small, one-room museum above the dojo that he has dedicated to the preservation of kobudo, Mr Nakamoto expounded on the ancient art. During the Ryukyu era, weapons were banned which gave birth to karate, which means "empty hands". The ancient combative art of kobudo is regarded as the precursor to karate and uses everyday implements such as hoes, oars and the tonfa – the wooden millstone handle that is the ancestor of the western truncheon. Next time you come under attack on a farm, try the horseshoe technique – doof, right between the eyes. On second thoughts, maybe not. Martial arts, climate, diet, and spirituality are all thought to contribute towards Okinawa's freakish longevity statistics. Locals enjoy the highest life expectancy on the planet, and is home to a remarkable number of centenarians. It pays to be adventurous with the area's largely plant-based diet. Within 48 hours I had eaten pig's face (it's everything but the squeak here), had a raw fish blow-torched at my table, wolfed down kilos of silky-smooth tofu (I hate tofu), licked 15 types of salt and grown addicted to a certain salty ice-cream. An ubiquitous purple tuber called imo goes down a treat in doughnut form, but the best place to sample Okinawa's bitter, bioflavonoidrich vegetables is at a small restaurant called Emi no Mise in the village of Ogimi, known for obvious reasons as the "centenarian village". I didn't question the 15-dish seasonal longevity menu. I just ate it: pond herring stewed with salt, seaweed tofu (reddish seaweed, carrot and skin of pig's face), handama (a slimy, iron-packed green-and-purple vegetable) and chilled shikuwasa noodle, made with stringy, crunchy seaweed, aloe vera and the juice of shikuwasa (a sort of citrus fruit). Washed down with locally grown hibiscus tea, it was not bad for a tenner. The morning after the awamori love sharing, Lupit was gone, leaving blue sky, a replenished water table and some foul hangovers in its wake. I didn't snorkel, dive, hike or sea kayak around any of Okinawa's other 159 islands, but I did get an eyeful of them on the flight back to Tokyo. The chances of coming home disappointed are, I reckon, pretty slim.