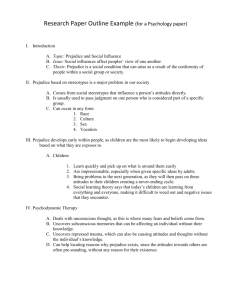

Prejudice - Ashton Southard

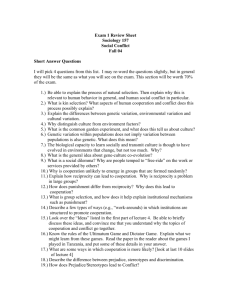

advertisement