Presentation1 Abnormal psychology 5.2 Concepts and

advertisement

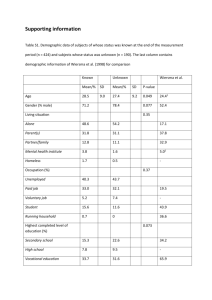

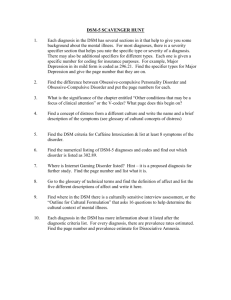

5.2 Concepts and diagnosis Examine the concepts of normality and abnormality. Discuss Discuss validity and reliability of diagnosis. cultural and ethical considerations in diagnosis. Abnormal Psychology 5.1 Introduction: What is abnormal psychology. ‘We all try to understand other people. Determining why another person does or feels something is not easy to do. In fact, we do not always understand our own feelings and behaviour. Figuring out why people behave in normal, expected ways is difficult enough; understanding seemingly abnormal behaviour can be even more difficult’.1 ‘Abnormal psychology is the branch of psychology that deals with studying, explaining and treating ‘abnormal’ behaviour. Although there is obviously a great deal of behaviour that could be considered abnormal, this branch of psychology deals mostly with that which is addressed in a clinical context. In effect, this means a range of behaviours, emotions and thinking that tend to result in an individual seeing a mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist or a clinical psychologist. Abnormal psychology attracts researchers who investigate the causes of abnormal behaviour and try to find the most effective treatments for them, whether these involve medication or talking cure or combination. There are also practitioners, psychologists who use their knowledge of theory and research to deliver treatment to people in a therapeutic setting. A large number of conditions occur commonly enough to be categorised systematically within various cultures and, in some cases, across the world. The IB psychology syllabus deals with only three groups: Anxiety disorders Affective disorders Eating disorders Defining these groups is straightforward because of the diagnostic systems available, The word normal usually refers to conformity to standard or regular patterns of behaviour. The concept of abnormality is essentially a label applied to behaviour that does not conform. Unfortunately, this explanation is not very precise and it remains difficult for mental health professionals to agree on who is abnormal enough to require or deserve treatment. Another way to decide what is abnormal is to assume that all humans perform behaviours that are good for them in their particular environment context. Behaviours that threaten one’s ability to function well within the social context can be considered maladaptive. This approach works well when we consider such conditions such as alcoholism and anorexia, where it is clear that a persons health is in danger. What else falls into this category? Discuss. Assumes average behaviour. Experiences between two people very subjective. Statistically unusual behaviour is attributed to mental illness, perhaps because assuming that people are suffering from some sort of psychiatric condition helps us understand the strangeness of their behaviour. Social norms are not necessarily related to statistical norms. The expected behaviour is that which the rules of society and culture dictate is appropriate for that context. When people violate such rules, we have a tendency to assume there is something wrong with them, and it is easy to attribute this to some kind of madness. However there are three key problems with this approach. First, social norms vary enormously across cultures and social institutions. (in your group think of an example) The second problem is historical variation. Past models of madness would now be acceptable. Thirdly, what is considered to be sociably acceptable or unacceptable has been established by groups with social power. (In your groups discuss who in your society/culture, makes the rules. Think about behaviour you have seen in another culture that you think is strange, then think about behaviour that is normal in your culture, but may seem strange by another. Why is culture so important? The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (DSM 1V) First published in 1952 and is constantly update. It is currently in its 4th editition. The DSM groups disorders into categories and then offers specific guidance to psychiatrists by listing the symptoms required for a diagnosis to be given. In your groups design a rubric to diagnose a mental disorder According to the DSM-IV, a person who suffers from Major Depressive Disorder must either have a depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities consistently for at least a two week period. This mood must represent a change from the person's normal mood; social, occupational, educational or other important functioning must also be negatively impaired by the change in mood. A depressed mood caused by substances (such as drugs, alcohol, medications) is not considered Major Depressive Disorder, nor is one which is caused by a general medical condition. Major Depressive Disorder cannot be diagnosed if a person has a history of Manic, Hypomanic, or Mixed Episodes (e.g., a Bipolar Disorder) or if the depressed mood is better accounted for by Schizoaffective disorder and is not superimposed on Schizophrenia, Schizophreniform Disorder, a Delusional Disorder or Psychotic Disorder. Further, the symptoms are not better accounted for by Bereavement (i.e., after the loss of a loved one) and the symptoms persist for longer than two months or are characterized by marked functional impairment, morbid preoccupation with worthlessness, suicidal ideation, psychotic symptoms, or psychomotor retardation. This disorder is characterized by the presence of the majority of these symptoms: Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report (e.g., feels sad or empty) or observation made by others (e.g., appears tearful). (In children and adolescents, this may be characterized as an irritable mood.) Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month), or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt nearly every day diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide. Definition: Panic disorder is a type of anxiety disorder. To have a diagnosis of panic disorder, you need to meet the following criteria. First, you need to have experienced a panic attack. The DSM-IV describes a panic attack as the experience of intense fear or discomfort where four or more of the following are experienced: pounding heart or increased heart rate sweating trembling or shaking feeling as though you are being smothered or having trouble breathing choking chest pain/discomfort nausea or abdominal pains and/or discomfort feeling dizzy, lightheaded, or faint feeling as though things around you are unreal or feeling detached from yourself feeling like you are going to lose control or go crazy fear of dying numbness or tingling in extremities chills or hot flashes To have a diagnosis of panic disorder, you must also have experienced recurrent unexpected panic attacks. These are panic attacks that occur "out of the blue," not triggered by anything in your environment. At least one of the attacks must be followed by one month or more of one or more of the following experiences: Concern about having additional panic attacks Worry about the consequences or implications of a panic attack (e.g., concern that your are going to die). A change in behavior because of the attacks. Panic disorder is a common condition. Approximately 5% of people will develop panic disorder at some point in their lifetime. The ICD 10 is more common and internationally used than the DSM. It was originally intended by the World Health Organisation to be a means of standardising recording of cause of death. It covers a wider range of disorders. With consultation and revision the differences between DSM and ICD are becoming becoming fewer. The CCMD focused on Chinese culture. Diagnosis for Ego-dystonic homosexuality included. Eating disorders. Only reconised in western diagnosis. There are strong arguments that these systems are not reliable and in some cases it is not valid to take such a medical approach. For example is it ethical to suggest that Ego-dystonic homosexuality is considered a disorder and therefore can be treated. Receiving a diagnosis can be a difficult experience for some and a huge relief for others. It is important to ask if the systems are reliable. Two key forms of reliability are: Inter-rater reliability; assessed by asking more than one practitioner to observe the same person, and using the same diagnostic system, attempt to make a diagnosis. One of the most famous studies was carried out by Nicholls et al. Two practitioners from Great Ormond St London used either the DSM1V or ICD 10 or the hospitals own (GOS) to diagnose 81 children with eating disorders. In groups discuss the data p,150. Do diagnostic systems need to be culturally specific? Gender specific? Age specific? The key concern for diagnostic systems is whether they correctly diagnose people who really have particular disorders and do not give a diagnosis to people who do not. Unfortunately, there is a circular logic involved here – it is difficult to establish whether a person truly has a disorder without using a diagnostic system Workbook. Summerise validity issues by examining the work of R.D Laing; Thomas Szasz. P150 Law et al Examine: Labelling theory (Caetona 1973) What is normal behaviour (Rosenham et al 1973) and Peters et al Criterian related validity Write a short paragraph to summerise the problems of validity illustrated by the Caetano, Rosehan and Peters studies.