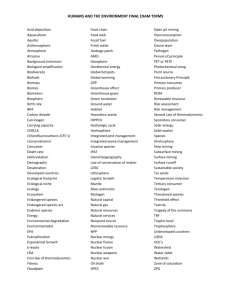

Circuit Debater

advertisement