End of Life Care - RCRMC Family Medicine Residency

advertisement

End of Life Care

Which of the following

is not documented in the Physician

Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment

Paradigm (POLST) form?

A) Instructions for resuscitation

B) Types of medical interventions

desired

C) Designation of durable power of

attorney for health care

D) Use of artificial nutrition and

hydration

Answer

• C) Designation of durable power of

attorney for health care

Choose the correct criteria for eligibility for

hospice care in a patient with dementia.

Lack of meaningful verbal communication (6 or

fewer words)

Hospitalization for pneumonia, pyelonephritis,

sepsis, or other serious complications in previous

6 mo

Presence of stage 3 or 4 pressure ulcers

Weight loss of ≥5% in previous 6 mo

Total dependence for activities of daily living

A)

B)

C)

D)

1,2,3,4

1,3,4,5

2,3,4,5

1,2,3,5

Answer

1. Lack of meaningful verbal

communication (6 or fewer words)

2. Hospitalization for pneumonia,

pyelonephritis, sepsis, or other serious

complications in previous 6 mo

3. Presence of stage 3 or 4 pressure

ulcers

5. Total dependence for activities of daily

living

•

D) 1,2,3,5

Appetite stimulants may

increase ________ in

patients undergoing

palliative care.

A) Enjoyment of eating

B) Lean body mass

C) Longevity

D) A, B, and C

Answer

• A) Enjoyment of eating

Choose the correct statement about

the benefits of artificial hydration

and nutrition (AHN).

A) AHN can relieve dry mouth

B) Percutaneous endoscopic

gastrostomy (PEG) tubes and total

parenteral nutrition increase patient

comfort

C) AHN may cause dyspnea from

pulmonary edema

D) PEG tubes help prevent

pneumonia from aspiration

Answer

• C) AHN may cause dyspnea from

pulmonary edema

Constipation is the only

side effect of treatment

with opioids for which the

patient does not develop

tolerance.

A) True

B) False

Answer

• A) True

Which of the following

is notuseful for the treatment

of nausea and vomiting

induced by administration of

opioids in the absence of

motility and distention

problems?

A) Haloperidol

B) Diphenhydramine

C) Scopolamine

D) Metoclopramide

Answer

• D) Metoclopramide

Both glycopyrrolate and

scopolamine cross the

blood-brain barrier and

may cause changes in

mental status.

A) True

B) False

Answer

• B) False

Approximately ________

of patients at end of life

suffer from cough.

A) 10%

B) 25%

C) 40%

D) 60%

Answer

• C) 40%

Unlike ________ for

treatment of opioid

induced constipation,

________ does not cause

opioid withdrawal and

reversal of analgesia.

A) Oral naloxone;

methylnaltrexone

B) Methylnaltrexone; oral

naloxone

Answer

• A) Oral naloxone;

methylnaltrexone

Which of the following

statements about

methylphenidate for the

treatment of depression in

patients with terminal illness

is(are) correct?

A) It is the fastest acting

antidepressant

B) It is well tolerated in

geriatric population

C) A and B

D) None of the above

Answer

• C) A and B

An 80-year-old patient is on high

doses of morphine to control pain

and dyspnea at the end of life. Which

one of the following medications is

appropriate for constipation caused

by opioids?

A. Corticosteroids.

B. Naloxone (formerly Narcan).

C. Ketamine (Ketalar).

D. Polyethylene glycol solution

(Miralax).

Answer

• D. Polyethylene glycol solution (Miralax).

A 78-year-old woman with terminal

breast cancer has been vomiting. She

complains of feeling anxious and

fearful about her rapid decline in

function. Which of the following

antiemetic medications is/are most

appropriate?

A. Benzodiazepines.

B. Cannabinoids.

C. Antihistamines.

D. Dexamethasone.

Answer

• A. Benzodiazepines.

B. Cannabinoids.

An 85-year-old man with severe

pneumonia is rapidly declining and

is not responding to antibiotics.

Which of the following actions can

help prevent delirium?

A. Keeping familiar persons at the

bedside.

B. Limiting medication changes.

C. Limiting unnecessary

catheterization.

D. Using wrist restraints.

Answer

• A. Keeping familiar persons at the bedside.

B. Limiting medication changes.

C. Limiting unnecessary catheterization.

What should the dose of

the pain medication be for

breakthrough pain? What

% of the 24 hour dose q 1

hour?

Answer

• 10 to 20%

PALLIATIVE AND END-OFLIFE CARE

• Approach to discussion: study of

interaction between hope and desire for

prognostic information among 55 patients

with terminal disease;

• 4 patterns—feelings swing between totally

hopeful and completely discouraged (amount

of information desired depended on stage)

• scales and balance (hopeful but realistic

• wanted information but not too much)

• yin-yang (hope and bad news coexisted)

• Redirected hope (from hope for cure to other

things, eg, survive to certain date)

• ask all patients how much information they

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

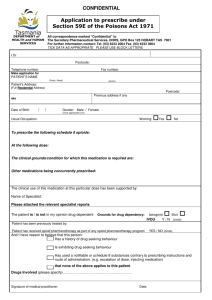

Advance

directive

Five Wishes form—includes designation of durable

power of attorney (DPOA) for health care

Type of medical treatment desired

degree of comfort desired

desired treatment

level of information shared with loved ones

does not direct paramedics about wishes regarding

code

Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment

Paradigm (POLST) form

provides instructions for resuscitation

types of medical interventions

use of antibiotics

artificial nutrition and hydration

does not designate DPOA

living will registry—available in Washington

patient sends copy of documents to central database

•

The Five Wishes

Wishes 1 and 2 are both legal documents. Once signed, they meet the legal

requirements for an advance directive in the states listed below. Wishes 3, 4 and

5 are unique to Five Wishes, in that they address matters of comfort care,

spirituality, forgiveness, and final wishes.

Wish 1: The Person I Want to Make Care Decisions for Me When I Can't

This section is an assignment of a health care agent (also called proxy, surrogate,

representative or health care power of attorney). This person makes medical

decisions on your behalf if you are unable to speak for yourself.

Wish 2: The Kind of Medical Treatment I Want or Don't Want

This section is a living will--a definition of what life support treatment means to you,

and when you would and would not want it.

Wish 3: How Comfortable I Want to Be

This section addresses matters of comfort care--what type of pain management you

would like, personal grooming and bathing instructions, and whether you would

like to know about options for hospice care, among others.

Wish 4: How I Want People to Treat Me

This section speaks to personal matters, such as whether you would like to be at

home, whether you would like someone to pray at your bedside, among others.

Wish 5: What I Want My Loved Ones to Know

This section deals with matters of forgiveness, how you wish to be remembered and

final wishes regarding funeral or memorial plans.

Signing and Witnessing Requirements

The last portion of the document contains a section for signing the document and

having it witnessed. Some states require notarization, and are so indicated in

the document.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Discussing palliative care

with patients

Timing

at time of diagnosis of life-limiting disease

if physician expects patient’s death in next 6 to 12 mo

if patient has frequent hospital admissions

if chronic disease progresses

if patient with chronic untreatable disease presents with lifethreatening event

that could allow natural death

set safe context for discussion

open with questions about patient’s goals for their experience

questions—identify stakeholders

ask about patient’s understanding of situation

sources of strength,

Hopes

Fears

past experiences with serious illness

keys to successful discussion

allowing patient and family time to speak increases patient satisfaction and

helps reduce anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and depression

among family members

Try to aim for 66/34 with patient family 66% of talking

Hospice eligibility for

patients with dementia

• criteria include

• total dependency for activities of daily living

(ADLs)

• lack of meaningful verbal communication (6

or fewer words)

• hospitalization for pneumonia, pyelonephritis,

sepsis, or other serious complication in

previous 6 mo

• stage 3 or 4 pressure ulcers

• loss of 10% of body weight in previous 6 mo

• patient must have any 3

Benefits of hospice:

• nurse on-call 24 hr/day

• skilled hospice certified nursing

assistant (CNA)

• spiritual support

• Comprehensive emotional and grief

support, with special programs for

children

• hospice volunteers

Anorexia

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

obtain history and laboratory or radiographic data (if appropriate), and perform physical examination to seek

cause

if possible, treat underlying cause (eg, reflux, constipation)

appetite stimulants—options

alcohol,

Steroids

Megestrol

delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol,

Androgens

do not increase lean body mass or longevity

may provide patients with enjoyment of eating

Artificial hydration and nutrition (AHN)

ask about patient’s goals

during nutritional deficiency

central nervous system endorphins may cause mild euphoria

intravenous (IV) fluids do not relieve dry mouth

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) do not prolong life

may increase suffering (eg, dyspnea from pulmonary edema or ascites

pneumonia from aspiration

discomfort from tube or IV

possible need for restraints in patients with dementia, loose stools)

appropriate for patients with malignancies of head and neck or upper gastrointestinal tract who are having

definitive surgery or receiving radiation or chemotherapy

selected ambulatory patients (eg,

patients with HIV)

patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

for patients with dementia, tube feeding does not prolong survival, prevent aspiration, Improve pressure

ulcers, improve function, or give comfort

Anorexia

• Study results

• not randomized

• median survival of 59 days among 23

patients who received PEG

• 60 days among 18 patients who did not

• Family concerns: encourage alternative

activities to show care for patient

• in case of conflicting wishes, perform

therapeutic trial of feeding tube for specific

time (eg, 3 days)

• Reassess

Questions and answers

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Letter of condolence: difficult but appreciated by family

Questions and answers: why does POLST form have full

resuscitation option?

allows patient to specify wishes for other measures, eg, AHN

also, documentation of wish for resuscitation on POLST form indicates

that patient has discussed their wishes for this option

can duration of hospice exceed 6 mo?

yes; most groups follow Medicare guidelines, which require that

attending physician expects patient’s death within 6 mo

patient’s condition re-evaluated at 90 days after admission and every

60 days thereafter

patient may remain in hospice as long as expectation of death within 6

mo remains after these evaluations

some insurance companies pay only for specific period

many hospices provide charity care afterwards

do gastroenterologists believe that PEG tubes prevent aspiration?

literature does not support conclusion that PEG tubes that end in

stomach prevent aspiration

Tubes that terminate in jejunum may prevent aspiration

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Letter of condolence

The benefit of writing a letter of condolence as twofold: to be a source

of comfort to the survivors and to help clinicians achieve a sense of

closure about the death of their patient. In the sidebar on the

previous page, Dr Mark Geliebter, Martinez, CA, describes how he

began writing letters of condolence to his patients and the value this

practice has had for him.

If you decide that writing a letter of condolence is a practice you

would like to begin incorporating into your medical practice, the

following guidelines, adapted from Wolfson and Menkin's "Writing a

condolence letter,"3 may be helpful.

Address the family member. Dear Mrs Wagner, ...

Acknowledge the loss and name the deceased. Dr Murphy and I were

deeply saddened today when we learned from your hospice nurse Lois

that your mother, Ruth Smith, had died.

Express your sympathy. We are thinking of you and send our heartfelt

condolences.

Note special qualities of the deceased. It seems like only yesterday

that Ruth talked about her love of card playing. I admired her energy

and quick wit.

Note special qualities of the family member. I was deeply moved by

the devotion you and your family showed during the period of Ruth's

final illness. Your concern was one indication of your love for her.

Although she was a fiercely independent woman, I know she

appreciated your involvement and help.

End with a word or phrase of sympathy. With affection and deep

sympathy, we hope that your fond memories of Ruth will give you

comfort.

Doctors and Sympathy Cards

By Mark Geliebter, MD

•

•

•

•

As soon as the Code Blue ends in the emergency department all of the housestaff scatter. During my training, I

was always struck by how quickly the doctors would leave the scene as soon as the patient was pronounced

dead. There was no lingering--as if no one wanted to stay in the room with the dead person. The strategy

seemed to be to create physical distance from any associated feelings of failure as a doctor. There was no ritual

to follow at the end of an unsuccessful resuscitation effort. There was never any discussion about the ritual of

death. We would spend weeks and weeks discussing the Krebs molecular "life cycle" in medical school.

However, discussions about the natural cycle of life and death were rare. After practicing internal medicine for

many years at Martinez, CA, I was struck by my own lack of closure when my patients died. I too would not

hover at the bedside when a patient of mine had died. I would not routinely connect with family members after

a death. Many years ago, I became involved in physician wellness efforts at my facility and regionally. I realized

that exploring our own relationship with death and dying was a key element in physician well-being.

One of the outcomes of that exploration was the decision to start a new practice for myself in 1995. I began to

list the name of every patient of mine who died. I generally would include a diagnosis, medical record number,

date and place of death. I started a folder labeled "Death and Dying." I also began to send a sympathy card to

each family (I later found these cards available as a KP stock item!).

Initially, I began with brief statements of sympathy. More recently, I've been writing more personal comments,

especially when I've had a longer relationship with the person or their family. I frequently mention that I felt

privileged to have been their physician. I also try to call the families that I feel connected to. I have received

frequent positive feedback from families for my personal note or call. They are most appreciative of my

thoughtful acknowledgments.

This has created a ritual practice for myself at the time of a patient's death. It also gives me a way to remember

my patients. When I review my list, I can usually remember something about them, their faces, their

personalities, or some ethical or medical issues that may have been challenging. Even after many years, the list

elicits those memories. I would have totally forgotten many patients that had died if it weren't for my list. At

times, it reminds me of memorial plaques on some synagogue or other walls that list names of members or

their families who have died. Sending the sympathy card and making the follow-up phone calls have become

part of my own sense of responsibility as a physician. It helps obviate the need to run out of the room after an

unsuccessful Code Blue, as I did when a medical student. Integrating the reality of death; embracing it as a

natural process; developing coping strategies; not labeling death as failure; finding rituals; doing outreach

during and after the dying process are all part of our role as physicians. All of these insights and rituals will add

to our own personal wisdom of dealing with the inevitability of our patients' and our own deaths.

Example Condolence Letter

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Below is an example of a condolence letter using the seven components above:

Dear_____________,1. Acknowledge the loss, refer to deceased by name.

I was deeply saddened to hear about the death of _____________.

2. Express your sympathy.

I know how difficult this must be for you. You are in my thoughts and prayers.

3. Note special qualities of the deceased.

____________was such a kind, gentle soul. She would do anything to help

someone in need.

4. Include your favorite memory.

I remember one time_________________.

5. Remind the bereaved of their personal strengths and qualities.

I know how much you will miss_______________. I encourage you to draw on

your strength and the strength of your family. You could use your special talent

of scrapbooking to make a lasting memory book of _________________.

6. Offer specific help.

I can come over on Tuesday evenings to help you make your scrapbook. I have

some lovely pictures of _______________ I’d love to share.

7. End the letter with a thoughtful closing.

May God bless you and your family during this time and always,

Sign your name_____________________

Keep in mind that this is only an example. Write from your heart and whatever

elements you include will be the right ones.

The next page includes information on writing a shorter version of the

condolence letter: The Condolence Note.

Condolence note

• You may decide to write a shorter version of a condolence

letter on note card or on a small piece of stationary tucked

inside a commercial card. If I am close enough to the

deceased to have photos of them, I especially like to print one

of my favorite photos on a card. That can be done from your

computer or from a picture program in your local photo

developing shop.

• When writing a condolence note, pick just a few elements

from the example on the first page of this article. Using

components #1, 2, 3, and 7 is a good guide.

1. Acknowledge the loss and refer to the deceased by name.

2. Express your sympathy.

3. Note any special qualities of the deceased that come to mind.

4. End the letter with a thoughtful word, a hope, a wish, or

expression of sympathy e.g. "You are in my thoughts" or

“Wishing you God’s peace.” Closing such as "Sincerely," "love,"

or "fondly," aren’t quite as personal.

• Remember that this is just a guide. You can use any of the

components of a condolence letter in your note or none at all.

The most important thing is to write from your heart

A letter by Abraham Lincoln

• Archival communications abound with

outstanding examples of fine letters of

condolence. A letter by Abraham Lincoln to a

girl whose father had died in the Civil War

showed several of the qualities outlined

above8:It is with deep grief that I learn of the

death of your kind and brave Father; and

especially that it is affecting your young heart

beyond what is common in such cases. In this

sad world of ours, sorrow comes to all; and,

to the young it comes with bitterest agony,

because it takes them unawares. The older

have learned ever to expect it.

• Note that Lincoln uses the word death directly

and describes her father as kind and brave.

Years later, one can only imagine how this

A Dying Art?

The Doctor’s Letter of Condolence

Gregory C. Kane, MD, FCCP

•

•

•

In their commentary on writing letters of condolence, Bedell et al5 outlined why

doctors do not regularly write letters of condolence. Potential explanations

included a lack of time, a loss for the appropriate expression of sympathy, a

feeling that they did not know the patient well enough, lack of a specific team

member responsible for writing the letter, or a sense of failure over the death.

No doubt, this has been fostered by a lack of role modeling or broader

discussion of such practices.

In a personal and memorable patient encounter, I sat and listened while a tearful

patient cried at having received no contact from the physician who treated her

husband for metastatic lung cancer for a treatment duration of 9 months. As I

struggled to comprehend her sense of pain and abandonment, I considered

offering as possible explanation that the physician may not have been “on call”

at the time of the death and may have mistakenly believed that his partner had

offered such a gesture verbally. Before I could respond, however, my patient

added that her veterinarian had sent a card when the family dog died. I was

speechless.

Other physicians have shared similar experiences, sometimes involving family

members, friends, or mutual patients. In his convocation speech on becoming

President of the American College of Chest Physicians in 2003, Dr. Richard

Irwin described a vision for patient-centered care. His vision was comprehensive

but also included a discussion of sympathy cards after the death of a patient. He

noted, “when physicians do not acknowledge the deaths of their patients, it is

perceived that physicians are silently saying that the deceased patient was not

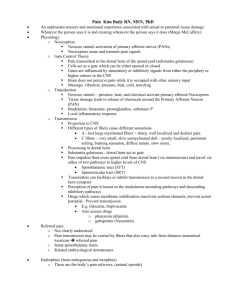

Nausea and vomiting (NV)

• consider possible causes

• Opioids: act on chemotactic trigger zone (rich in dopaminergic

receptors) and on vestibular system (may manifest after

changing position)

• data unclear whether NV side effects similar for all opioids

• patients eventually become tolerant

• constipation only side effect of opioids for which no tolerance

develops

• if NV mild, continue drug until tolerance develops

• if NV severe, rotate to other opioids

• Antiemetics haloperidol, scopolamine (anticholinergic) or

promethazine (Phenergan); antihistamine diphenhydramine

(Benadryl) also works well

• 5HT3 antagonists (eg, ondansetron) not generally helpful for

managing opioid-mediated NV

• Haloperidol most potent antidopaminergic, followed by

prochlorperazine

• promethazine has minimal antidopaminergic properties

• metoclopramide (Reglan) binds few receptors relevant to NV

• useful only for problems with motility and distention

Bowel obstruction

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

most often associated with pelvic cancer, especially ovarian and colon

symptoms include NV and cramping abdominal pain

treatments surgical, interventional, and medical

usually possible to avoid IV and nasogastric tube

Surgical treatment: includes venting gastrostomy tubes for small bowel

obstructions but not for colonic obstructions

Drug therapy: cocktail of opioids, anticholinergic agent, and somatostatin

(octreotide)

opioids—help relieve pain; evidence suggests they do not increase risk for

paralytic ileus

dopamine antagonist—eg, haloperidol; much lower dose (ie, 0.5 to 2 mg every

4-6 hr) of haloperidol required than for psychosis (5 to 10 mg)

spasms; agents include glycopyrrolate or scopolamine

glycopyrrolate administered IV or PO) and does not cross blood-brain barrier or

cause changes in mental status

scopolamine administered by patch and crosses blood-brain barrier

consider prokinetic drugs for partial small bowel obstruction and discontinue if

pain increases

octreotide—inhibits splanchnic blood flow and decreases secretions from

intestinal mucosa to diminish distention

administered IV or subcutaneously

Effective dose usually <400 g/day

Cough

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

highly debilitating; 40% of patients suffer from cough at end of life

drugs associated with cough include

angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

agents (NSAIDs), and propellants in inhaled medications

Treatment: American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends against

use of prescription and over-thecounter cough syrups

sweet syrups (eg, honey) possibly effective for relief of cough

Opioids first-line therapy for cough in patients with cancer

all opioids have similar effect

for patients already taking an opioid, study suggested low dose of oxycodone

effective a 5 mg po bid

Expectorants consider for wet cough

guaifenesin or inhaled acetylcysteine

avoid in patients with reactive airway disease because of bronchospasm

consider nebulized 3% to 10% hypertonic saline instead

use caution in patients with impaired cough reflex because of risk for aspiration

benzonate—local anesthetic second-line in addition to opioids

anticholinergics—play role if upper airway secretions contribute to cough (eg,

scopolamine and glycopyrrolate);

inhaled lidocaine—(used off-label)

bupivacaine block upper airway stretch receptors

Patients must not eat or drink for 1 hr after inhalation as precaution against

aspiration

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Constipation

experienced by 90% of patients in advanced phases of illness

mostly due to opioids

prevention critical, and all patients on opioids need bowel regimen

Constipation can cause fecal impaction and diarrhea

Digital rectal examination and history important

preventive regimen includes stool softener, eg, docusate (Colace), and stimulant

laxative, eg, senna or bisacodyl (Dulcolax)

add osmotic laxative if necessary

Induced by opioids

tolerance rarely develops

not centrally mediated, limited to gut

previously used oral naloxone (opioid antagonist with poor bioavailability)

However high doses needed cause opioid withdrawal and reversal of analgesia

methylnaltrexone—mu receptor antagonist that works only in gut

given as subcutaneous injection

lower dose works better

in studies, 60% of patients have bowel movement (BM) within 4 hr and 70%

within

first 24 hr

in clinical use, 54% have BM

no tolerance observed

average dose 8 mg (based on weight)

Comes in prefilled syringe

side effects include abdominal cramping, gas, and diarrhea

Metastatic bone pain

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

almost 500,000 new patients per year

often associated with cancers of lung, breast, and prostate and multiple myeloma

goals of treatment include

control of pain and prevention of fractures

Medical therapy: consider calcitonin because of low risk, although often not efficacious, and

effect short-lived when present

opioids—effective only 50% of time

NSAIDs—treat inflammation in bone

avoid indomethacin in elderly patients because of associated CNS toxicity and mental status

changes

ibuprofen (eg, Motrin) at anti-inflammatory doses (ie, 600 to 800 mg/day)

corticosteroids—mechanism similar to that of NSAIDs

dose not standardized

prednisone and dexamethasone (eg, Decadron) most commonly prescribed

Dexamethasone used at 16 to 32 mg/day for bone pain

start at 2 to 4 mg twice daily because of dose-limiting toxicity

Discontinue if not effective after 7 days at 16 to 24 mg

prednisone used at 30 to 40 mg/day

dexamethasone has lower mineralocorticoid activity than prednisone

bisphosphonates—(eg, zoledronic acid and pamidronate) decrease bone pain

most effective in breast and prostate cancer

inhibit bone resorption by osteoclasts

reduce number of fractures and skeletal events by 30%

reduce pain by 30% to 40% in 30% to 50% of patients

effects last 3 to 4 wk

if first infusion not effective, try second infusion, but if still ineffective, discontinue for pain

(may continue for fractures)

Metastatic bone pain

• Radiation therapy: effects on pain seen in 2 days to 2

weeks

• limited by number of areas affected by metastasis

• Radiopharmaceuticals: Strontium, best evidence for

efficacy in breast and prostate cancer; helpful with

multiple foci of metastasis

• improve pain in 30% of patients

• patient must have >12 wk of life remaining

• analgesia occurs as soon as 3 days, usually 2 wk

• worsened pain (flare) within first week because of

inflammatory effect (actually good prognostic sign)

• myelosuppression can occur (cancer patients who

already have myelosuppression from tumor not

candidates)

• Neuropathic bone pain: component of bone pain

• early data show benefit of gabapentin (Neurontin) or

Psychiatric symptoms

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

depression not part of dying but manageable symptom

antidepressants can help achieve better pain control

anxious depression often misdiagnosed as anxiety disorder

methylphenidate—fastest acting antidepressant

appropriate for patients with life expectancy of weeks

response observed within 1 or 2 doses

well tolerated in geriatric population

begin dose at 2 to 5 mg once daily and add 2.5 mg if no effect

ultimately may need only 5 mg twice daily

duloxetine (Cymbalta) and venlafaxine (Effexor) appropriate for patients

with depression and neuropathic pain

fluoxetine and venlafaxine appropriate to activate patients with

psychomotor retardation

Mirtazapine (Remeron) useful for depression with insomnia

Also stimulates appetite in patients without severe depression when

given at 7.5 mg at night

citalopram, escitalopram, and paroxetine helpful for depression with

anxiety

Suggested Reading

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Abernethy AP et al: Detailing of gastrointestinal symptoms in cancer

patients with advanced disease: new methodologies, new insights,

and a proposed approach. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 3:41,

2009; Al-Khafaji A, Min Cho S: Making palliative care more “palatable.”

Crit Care Med 37:2492, 2009; Biermann JS et al: Metastatic

bone disease: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. J Bone Joint

Surg Am 91:1503, 2009; Dalal S et al: Is there a role for hydration at

the end of life? Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 3:72, 2009; Desandre

PL, Quest TE: Management of cancer-related pain. Emerg Med

Clin North Am 27:179, 2009; Di Giulio P et al: Dying with advanced

dementia in long-term care geriatric institutions: a retrospective

study. J Palliat Med 11:1023, 2008; Guay DR: Methylnaltrexone

methobromide: the first peripherally active, centrally inactive opioid

receptor-antagonist. Consult Pharm 24:210, 2009; Innes S, Payne S:

Advanced cancer patients’ prognostic information preferences: a review.

Palliat Med 23:29, 2009; Jacobsen J, Jackson VA: A communication

approach for oncologists: understanding patient coping and

communicating about bad news, palliative care, and hospice. J Natl

Compr Canc Netw 7:475, 2009; Kierner KA et al: Attitudes of patients

with malignancies towards completion of advance directives.

Support Care Cancer May 31, 2009 [Epub ahead of print]; MessingerRappaport BJ et al: Advance care planning: Beyond the living

will. Cleve Clin J Med 76:276, 2009; Monturo C: The artificial

nutrition debate: still an issue … after all these years. Nutr Clin Pract

24:206, 2009; Phelps AC et al: Religious coping and use of intensive

life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer.

JAMA 18:301, 2009; Price A, Hotopf M: The treatment of depression

in patients with advanced cancer undergoing palliative care.

Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 3:61, 2009; Rondeau DF, Schmidt

TA: Treating cancer patients who are near the end of life in the emergency

department. Emerg Med Clin North Am 29:341, 2009; Sanft

TB, Von Roenn JH: Palliative care across the continuum of cancer

care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 7:481, 2009; Wee B: Chronic cough.

Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2:105, 2008; Wright AA et al: Associations

between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health,

medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment.

JAMA 300:1665, 2008; Zaider T, Kissane D: The assessment and

management of family distress during palliative care. Curr Opin Support

Palliat Care 3:67, 2009.

dyspnoea

• Breathlessness or dyspnoea is the

unpleasant awareness of difficulty

in breathing

• dyspnoea, like pain, is subjective and

involves both the perception of

breathlessness and the reaction of the

patient to it

• dyspnoea is always associated with

some degree of anxiety, which in turn

will make the breathlessness worse

Treatment

• treatment directed at the specific

cause, where possible and appropriate

• general measures

• calm, reassuring attitude

• nurse patient in position of least

discomfort

• physiotherapy

• improve air circulation

• distraction therapy

• relaxation exercises

• breathing control techniques

• counselling

Is O2 saturation is a good

measure of dyspnea?

• True

• False

Answer

• False

• Dyspmea is a subjective symptom

Treatment

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

oxygen

if hypoxic

if it improves symptoms (terminal care situation)

Patients often feel better but it may be just do to movement of air on the face

A fan or open window may help just as much in certain situations

bronchodilators if there is a reversible element to the bronchial obstruction

corticosteroids

effective bronchodilators

for dyspnoea due to multiple metastases, lymphangitis carcinomatosis and

pneumonitis

opioids—the most useful agents in the treatment of dyspnoea

nebulised morphine

effective for some patients, although controlled studies do not support its use

risk of bronchospasm

aid expectoration

steam, nebulised saline

mucolytic agents

expectorants

Physiotherapy

reduce excess secretions

anticholinergics

antitussives if dyspnoea exacerbated by coughing

anxiolytics

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Examples of drug therapy

bronchodilators

salbutamol by metered aerosol or 2.5-5 mg by nebuliser, q4-6h

ipratropium by metered aerosol or 250-500 µg by nebuliser, q6h

aminophylline, theophylline PO

corticosteroids

prednisolone 40-60 mg/d PO or dexamethasone 8-12 mg/d PO

wean to the minimum effective dose after a few days

opioids

morphine 5-10 mg PO, q4h or 4-hourly PRN and titrate

50% increase in dose for patients on morphine for pain

nebulised morphine not recommended

anxiolytics

diazepam 2 mg PO q8h ± 5-10 mg nocte

alprazolam 0.25-0.5 mg SL, q1-2h

lorazepam 0.5-1 mg SL, q4-6h

mucolytics (for sputum retention)

humidified air (steam, nebulised saline)

acetylcysteine 10%, 6-10 ml by nebuliser, q6-8h

anticholinergics (for excessive secretions)

glycopyrrolate 0.2-0.4mg SC q2-4h or 0.6-1.2mg/24h CSCI

hyoscine hydrobromide 0.2-0.4mg SC q2-4h or 0.6-1.2mg/24h CSCI

Terminal Care

treatment should be purely symptomatic in the last week or days of life

investigations should be avoided

antibiotic therapy is usually not warranted

if of benefit, bronchodilator therapy can be continued by mask.

unconscious patients who still appear dyspnoeic should be treated with

morphine SC

TERMINAL RESPIRATORY

CONGESTION

('DEATH RATTLE')

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Terminal respiratory congestion is the rattling, noisy or gurgling respiration of

some patients who are dying

Cause

accumulation of pharyngeal and pulmonary secretions in patients who are unconscious or

semi-conscious and too weak to expectorate

Treatment

therapy is often more for the comfort of the relatives and other patients, as most

of the patients are no longer aware of their surroundings

position the patient on their side

oropharyngeal suction should be reserved for unconscious patients

anticholinergic drugs to suppress the production of secretions

hyoscine hydrobromide

0.4mg SC, ± repeat at 30min, then q2-4h or 0.6-1.2mg/24h CSCI

antiemetic; sedative; occasional agitated delirium

glycopyrollate

0.2-0.4mg SC, ± repeat at 30min, then q4-6h or 0.6-1.2mg/24h CSCI

less central and cardiac effects

atropine

0.4-0.8mg SC q2-4h

may cause tachycardia after repeated injections

transdermal scopolamine patches

hyoscine hydrobromide 1.5mg patch q72h

onset of action is delayed for several hours during which other anticholinergic treatment

needs to be given

reassure relatives that the noisy breathing is not causing any added suffering for

the patient

•

Pharmacologic Pearls for

End-of-Life Care

As death approaches, a gradual shift in emphasis from curative and life

prolonging therapies toward palliative therapies can relieve significant

medical burdens and maintain a patient's dignity and comfort.

• Pain and dyspnea are treated based on severity, with stepped

interventions, primarily opioids.

• Common adverse effects of opioids, such as constipation, must be treated

proactively; other adverse effects, such as nausea and mental status

changes, usually dissipate with time.

• Parenteral methylnaltrexone can be considered for intractable cases of

opioid bowel dysfunction.

• Tumor-related bowel obstruction can be managed with corticosteroids and

octreotide.

• Therapy for nausea and vomiting should be targeted to the underlying

cause; low-dose haloperidol is often effective.

• Delirium should be prevented with normalization of environment or

managed medically. Excessive respiratory secretions can be treated with

reassurance and, if necessary, drying of secretions to prevent the

phenomenon called the "death rattle."

• There is always something more that can be done for comfort, no matter

how dire a situation appears to be.

• Good management of physical symptoms allows patients and loved ones

the space to work out unfinished emotional, psychological, and spiritual

issues, and, thereby, the opportunity to find affirmation at life's end.

Clinical recommendation

•

Opioids should be used for dyspnea at the end of life.

• A

• Multiple studies have shown that nebulized opioids have no benefit over

systemic administration in terms of effect or adverse effects.

• Opioids should be used for pain at the end of life.

• C

• The ethical limitations of withholding opioids have limited the study of

opioids versus placebo, except in neuropathic pain.

• Stimulant laxatives are effective for prevention and treatment of

constipation in persons on opioids.

• C

• There is no clear benefit of one regimen over another.

• Methylnaltrexone (Relistor) can be used for treatment of opioid bowel

dysfunction.

• B

• Methylnaltrexone has recently been added as a treatment option.

• Corticosteroids can be used for malignant bowel obstruction.

• B

• Haloperidol (formerly Haldol) is effective for nausea and vomiting.

• B

• 34, 35

• Hyoscyamine (Levsin) should be used for the "death rattle" (excessive

respiratory secretions).

• C

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Methylnaltrexone (Relistor)

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION

These highlights do not include all the information needed to use

RELISTOR safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for

RELISTOR.

RELISTOR (methylnaltrexone bromide) Subcutaneous Injection

Initial U.S. Approval: 2008

————————— INDICATIONS AND USAGE —————————

RELISTOR is indicated for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation in

patients with advanced illness who are receiving palliative care, when

response to laxative therapy has not been sufficient. Use of RELISTOR

beyond four months has not been studied. (1)

——————— DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ———————

RELISTOR is administered as a subcutaneous injection. The usual schedule is

one dose every other day, as needed, but no more frequently than one dose in

a 24-hour period. (2.2)

The recommended dose of RELISTOR is 8 mg for patients weighing 38 to

less than 62 kg (84 to less than 136 lb) or 12 mg for patients weighing 62 to

114 kg (136 to 251 lb). Patients whose weights fall outside of these ranges

should be dosed at 0.15 mg/kg. See the table below to determine the correct

injection volume. (2.2)

Patient Weight

Pounds Kilograms

Injection

Volume Dose

Less than 84 Less than 38 See below* 0.15 mg/kg

84 to less than

136

38 to less than 62 0.4 mL 8 mg

136 to 251 62 to 114 0.6 mL 12 mg

More than 251 More than 114 See below* 0.15 mg/kg

*The injection volume for these patients should be calculated using one of

the following (2.2):

Multiply the patient weight in pounds by 0.0034 and round up the

volume to the nearest 0.1 mL.

Multiply the patient weight in kilograms by 0.0075 and round up

the volume to the nearest 0.1 mL.

In patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance less than

30 mL/min), dose reduction of RELISTOR by one-half is recommended. (8.6)

——————— DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS ———————

12 mg/0.6 mL solution for subcutaneous injection in a single-use vial. (3)

—————————— CONTRAINDICATIONS —————————

RELISTOR is contraindicated in patients with known or suspected

mechanical gastrointestinal obstruction. (4)

——————— WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ————————

If severe or persistent diarrhea occurs during treatment, advise patients to

discontinue therapy with RELISTOR and consult their physician. ( 5.1)

—————————— ADVERSE REACTIONS ——————————

The most common (> 5%) adverse reactions reported with RELISTOR are

PAIN AND DYSPNEA

•

Pain and dyspnea are treated based on severity, with stepped

interventions, primarily opioids.

• Dyspnea that persists despite optimal respiratory treatment is

sensed in the same central nervous system structures as pain and

should be considered as if it were "lung pain."

• Moderate to severe dyspnea and pain may be treated with oral or

parenteral opioids.1,6,7

• Proven nonpharmacologic strategies should be optimized.8

• Using one of many validated scales, physicians can support

patients' efforts to set realistic goals for function and pain or

dyspnea levels.

• Recommended scales should include assessment of intensity and

quality of pain, as well as function.

• Scales that include a nonverbal 0 to 10 line, faces scales, and

intensity descriptive scales have proven reliable in persons with

Mini-Mental State Examination scores averaging as low as 15.3

out of 30.9

• For nonverbal patients, other scales, such as the Pain

Assessment in Advanced Dementia scale, are necessary

•

Pain Control

Nonopioid pain therapies should be optimized; nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, steroids, and bisphosphonates are particularly

effective for bone pain.1,4,6

• A variety of medications are also available for neuropathic pain, a subject

beyond the scope of this article.

• The fear that opioids will hasten death is an inappropriate barrier to their

use, assuming proper dose initiation and escalation are used.11

• Opioids are a central part of pain treatment in palliative care, including

treatment of nonmalignant and neuropathic pain.12

• Titration for effective pain management should be rapid and consistent,

using parenteral or oral short-acting medications, with dosing intervals set

according to peak effects rather than duration of action.13

• Breakthrough dosing must be proportionate to the total 24-hour dose of

opioids.

• It should be 10 to 20 percent of the 24-hour oral morphine equivalent (or 50

to 150 percent of the hourly intravenous rate).

• A common error is the administration of 5 to 10 mg of oxycodone

(Roxicodone) for breakthrough pain when a patient is tolerating high longacting doses.

• For example, if a patient requires 1,000 mg of oral morphine equivalent

every 24 hours, the appropriate breakthrough dose would be 60 to 120 mg

of oxycodone.

• Breakthrough doses should treat unpredictable spikes in pain and prevent

breakthrough pain when predictable, such as before necessary turning or

transfers. Increases in the basal dose should be 25 to 50 percent for mild

to moderate pain and 50 to 100 percent for severe pain.

Pain Control

•

To control symptoms, breakthrough doses should be administered each time an increase in a basal

dose is initiated.

•

Preparations that combine an opioid with acetaminophen, aspirin, or ibuprofen should be avoided

because of the risk of toxicity above established dose ceilings of the nonopioid.14

•

Many patients with terminal illnesses and their families are reluctant to begin opioid therapy

because of the stigma associated with addiction.

•

Preparatory reassurance, education of the patient and family, and use of the term "opioids" instead

of "narcotics" helps.

•

If a persistent objection is raised to initiating one opioid, another can be substituted.

•

Failure of one opioid at the highest tolerated dose may be treated by rotation to another opioid.

•

Reduce dose equivalents by 50 to 75 percent when rotating opioids in the context of well-controlled

pain to compensate for incomplete cross-tolerance.

•

Dose ceilings of opioids are variable and often high.

•

Methadone is among the most difficult and dangerous to use, but has advantages in cost and

effectiveness. Physicians should consider consultation with a palliative care specialist before using

methadone, unless they are familiar with its interactions, variable duration of effect, adverse

effects, unique comparative potency with morphine, and risk of toxicity, including QT interval

prolongation.

•

The New Hampshire Hospice and Palliative Care Organization's opioid use guidelines

(http://www.nhhpco.org/opioid.htm) provide a quick reference card that reviews opioid

management and includes equianalgesic tables, opioid rotation guidelines, and a methadone and

morphine nomogram.13

•

Common causes of a partial response or lack of response to opioids include: neuropathic pain;

social, psychological, or spiritual pain; substance use disorders; and misinterpretation of

symptoms for pain, particularly in persons who are cognitively impaired.

•

Sometimes, aggressive therapies for pain control, such as surgery, radiation, regional nerve blocks,

and intraspinal or epidural delivery devices, are appropriate and necessary when basic measures

fail and interventions are consistent with patient goals.

•

Throughout treatment, physicians must evaluate the "total pain syndrome" and align treatment with

the causes of pain as much as possible, optimizing psychological, social, and spiritual treatments

and avoiding inappropriate pharmacologic management of psychosocial or spiritual pain.

Opioids

•

•

•

•

•

Steps to Rotate or Change Opioids

1. Calculate 24 hr dose of current drug.

2. Translate that to equianalgesic 24 hr dose of oral morphine.

3. Calculate 24 hr equianalgesic dose of new drug and reduce dose to

50-75% of calculated dose if pain is well controlled; use 100%

otherwise.

4. Divide to attain appropriate interval and dose for new drug.

5. Always have breakthrough dosing available while making changes.

Breakthrough Dosing (immediate release (IR) / short acting meds

only)

50-150% of IV basal dose q15 minutes OR 10-20% of 24 hr oral

dose q1hr.

Changing Basal Rates (due to inadequate baseline pain control)

Increase rate by 50-100% of IV basal rate q15 minutes.

Give a breakthrough dose each time basal rate is increased.

Ceiling Effect = uncontrollable pain with appropriate increases in

dose OR side effects such as neuroexcitation, myoclonus, or

protracted central effects.

a) Rotate to another opioid as above.

b) Dose reduce opioid by 25-50% with addition of other treatment for

pain.

c) Treat side effect +/- dose reduce.

Partial Reversal with Naloxone: ONLY for overdose in rare cases:

à mix 0.4 mg amp with saline to make 10cc + administer 0.5 -1 ml

(0.02-0.04 mg) IV/SC q2-5 minutes until response; naloxone effect

shorter in duration than long acting opioids and close monitoring +/-

METHADONE

•

•

•

METHADONE

CAUTION: Use only with experience or training in pain mgt.

- Dosing interval is titrated for analgesic effect q4-12h; start

with q8h.

- Delayed side effects @ Day 4 after initiation: highly lipid

soluble with potential delayed and prolonged side effects that

outlast analgesic efficacy.

- Prolonged QT at high dose>200 mg/day; interactions at

CYP450 (esp 2D6, 3A4)

- Common drugs that increase methadone effect: SSRI’s

(fluoxetine), TCA’s (amitriptyline), macrolides, metronidazole,

grapefruit juice.

- Decrease methadone effect: antiretrovirals, carbamazepine,

rifampin, phenytoin.

Rotation to Methadone

Day 1: Calculate dose (above). Give 33% methadone dose +

66% of present drug.

Day 2: Give 66% methadone dose + 33% present drug.

Day 3: Give 100% methadone dose.

Rotation from Methadone

Caution: Ratios above do not necessarily apply – consult an

Transdermal Fentanyl

• Rotating to and from Transdermal

Fentanyl (TDF)

Shortcut: Transdermal Fentanyl

(mcg/hr) X 2 = approx 24 hr dose of

MS PO(mg).

From TDF: Start new drug at 50% dose

for 6-24 hrs after removal of TDF.

To TDF: Continue old drug at 50% dose

for 6-24 hrs after starting TDF.

Bowel Routine

• Bowel Routine

All patients on opioids should be on a baseline bowel

routine such as one or more of the following:

Senna + docusate (Senokot S) 1-2 tabs twice daily.

MOM 30-60 cc twice to three times daily.

Lactulose 30-60 cc twice to three times daily.

PEG solution: Miralax 1-4 T daily or 4-8 oz of

GoLytely titrated to effect.

• STEP UP: If symptoms of constipation, lack of BM for

specified period of time, or risk factors present such as

immobilization, hospitalization, significant increase in

opioids:

Double dose of regimen above OR add 2nd agent

such as Lactulose or Miralax.

RECTAL IMPACTION or significant rectal stool:

Empty rectum first with:

Bisacodyl 10 mg pr bid for 1-3 days or Fleet or other

enemas until clear. Then proceed with stepped up bowel

regimen as above.

Opioid Adverse Effects

•

Nausea and vomiting, sedation, and mental status changes are common with opioid initiation and

most often fade within a few days.

•

When initiating an opioid, prophylactic use of an antiemetic for three to five days can be effective

in the susceptible patient.15

•

Persistent nausea and vomiting is related to chemoreceptor trigger zone stimulation, and can be

treated with a combination of dose reduction, opioid rotation, and antiemetics.16

•

Undesirable sedation can be addressed with low-dose methylphenidate (Ritalin), which can be

rapidly tapered when no longer needed.17

•

Allergy to opioids usually amounts to nothing more than sedation or gastrointestinal adverse

effects, and can be managed expectantly.

•

Localized urticaria or erythema at the site of an injection of morphine is caused by local histamine

release and is not necessarily a sign of systemic allergy.

•

Constipation is one adverse effect of opioids that does not extinguish with time (Table 2).18 An

important principle of pain management is that, when writing opioid prescriptions, physicians also

need to write orders for the bowel preparation. Increasing fiber or adding detergents (e.g., forms of

docusate) is not sufficient.

•

Like pain, constipation is more easily prevented than treated. Start a conventional combination of a

stimulant laxative with a stool softener (e.g., senna with docusate) or osmotic agent (e.g.,

polyethylene glycol solution [Miralax]) at the same time as the opioid.19

•

There is no good evidence of superiority of any one regimen over another.20 Polyethylene glycol

solutions are easy to titrate, with no maximal dose; can be given once daily; and are particularly

effective with the addition of a stimulant, such as senna.

•

With increases in opioid dose, or with other risks of worsening constipation (e.g., change in

environment, declining performance status), the laxative dose should be doubled or therapy

stepped up by adding a stronger agent.

•

Dosing can be ordered with the notation "hold for diarrhea" or a stepped action plan can be

developed based on consistency and frequency of stool.

•

Overflow diarrhea can occur with fecal impaction. Patients nearing death decrease their intake of

solids, which is often expected to cause the cessation of bowel movements.

•

However, 70 percent of the dry weight of stool consists of bacteria, so bowel activity can and

should be maintained for comfort.21

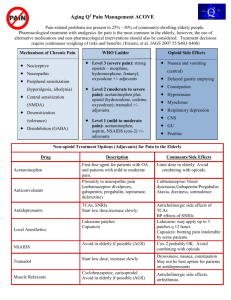

Treatment of Constipation

• Treatment

• Dosage

• Lactulose

• 15 to 30 mL orally two or three times per day

• Magnesium hydroxide

• 30 to 60 mL orally at bedtime

• Polyethylene glycol (Miralax)

• One or more tablespoons dissolved in 4 to 8 oz of fluid

orally per day

• Senna with docusate

• One to two tablets orally two to four times per day

Opioid Side Effects

•

Opioid bowel dysfunction that is unresponsive to aggressive conventional

medications, removal of anticholinergic or other contributing medications, enemas,

opioid dose rotation, and opioid reduction may be carefully treated with

methylnaltrexone (Relistor).22

•

It reverses mu-opioid receptor-mediated bowel paralysis without crossing the bloodbrain barrier.

•

In a recent industry-sponsored phase 3 trial, subcutaneous methylnaltrexone at 0.15

mg per kg led to a bowel movement within four hours in 48 percent of terminally ill

patients with opioid bowel dysfunction versus 15 percent with placebo, with a median

time of 45 minutes to first bowel movement versus 6.3 hours with placebo.23

•

A more recent study found a dose of 5 mg to be effective, but did not find a dose

response above 5 mg.24

•

Methylnaltrexone is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this

indication.

•

Toxic effects of opioids at higher dose ranges or with rapidly escalating doses

include forms of neuroexcitation, such as hyperalgesia, delirium, and myoclonus.25

•

A common pitfall is to confuse these symptoms with worsening pain and further

escalate the dose, which may worsen neuroexcitation and increase hyperalgesia,

thereby exacerbating total pain.

•

Opioid reduction or rotation, with the addition of adjuncts for pain control, is

indicated instead.

•

Ketamine (Ketalar) can be an effective adjunct in severe cases, but requires

experience or consultation.26

•

Unintentional overdose of an opioid can usually be managed expectantly; however, if

partial reversal is necessary, very low-dose naloxone (formerly Narcan) can be

quickly administered by giving 0.01- to 0.04-mg (or 1.5 mcg per kg) intravenous or

intramuscular boluses every three to five minutes, titrated to respiratory rate or

mental status (mix one 0.4 mg per mL ampule of naloxone with saline to make 10 mL,

which equals 0.04 mg per mL).27

•

Continued close monitoring is necessary because duration of opioid effect may

outlast naloxone.

Bowel Obstruction Nausea

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Mechanical bowel obstruction is commonly associated with ovarian28 and colon cancers.29

If this cause is known or suspected, it is acceptable to opt not to proceed to invasive intervention

urgently.30

•

Surgery or venting gastrostomy tube insertion should be undertaken only after careful

consideration, because of potential procedural complications, lack of evidence for life

prolongation, and recurrence rates up to 50 percent.31

Endoscopic bowel stenting can be a reasonable option for esophageal or duodenal obstruction.

•

Standard conservative therapies may include cessation of oral intake, transient nasogastric

suction, antiemetics, octreotide (Sandostatin), and corticosteroids.

•

Octreotide inhibits the accumulation of intraluminal intestinal fluid and can be administered

subcutaneously or intravenously at 50 to 100 mcg every six to eight hours and titrated rapidly to

effect.32

•

It is also available in an intramuscular depot form, but this form costs more.

Dexamethasone six to 16 mg intravenously daily may resolve a bowel obstruction caused by edema

from gastrointestinal or ovarian cancer.33

•

Although there is no change in mortality at one month, a review of 10 trials confirmed that

corticosteroids shrink swelling around the tumor and can allow resumption of oral intake with

reinstatement of normal bowel activity (number needed to treat = 6).33

Tapering off corticosteroids should not be undertaken in this circumstance unless indicated for

other reasons.

Persistent nausea and vomiting (without bowel obstruction) should be carefully investigated and

treatment directed to the underlying cause, most commonly in the central nervous system or the

gastrointestinal tract (Tables 3 and 4).34

If one medication fails, substitute another drug from a different class. Promethazine (Phenergan), a

sedating antihistamine, is relatively ineffective in palliative care and is overused.

As noted in a comprehensive review,34 off-label use of haloperidol (formerly Haldol), a low-cost

antiemetic, can be at least as effective as ondansetron (Zofran).35

It is best used at lower doses than for psychosis and can be combined with other interventions.

Choice of Antiemetic Based

on Cause of Nausea and

Vomiting

•

Cause of nausea and vomiting

• Antiemetic

• Anxiety, anticipatory, psychologic

• Benzodiazepines, canniboids

• Bowel obstruction

• Octreotide (Sandostatin; see text)

• Gastroparesis

• Metoclopramide (Reglan)

• Increased intracranial pressure, central nervous system pain

• Dexamethasone

• Inner ear dysfunction (rare in palliative care)

• Anticholinergics, antihistamines

• Medication (primarily chemotherapy)

• 5-HT3 and dopamine receptor blockers

• Metabolic (e.g., uremia, cirrhosis)

• 5-HT3 and dopamine receptor blockers, antihistamines, steroids

• Opioid bowel dysfunction

• Methylnaltrexone (Relistor)

DELIRIUM AND THE

"DEATH RATTLE"

•

Up to 85 percent of patients experience delirium in the last weeks of life, up 46 percent with

agitation.36

•

It manifests as a sudden onset of worsened mental status with agitation.

•

This distressing symptom often occurs in those with rapidly escalating opioid requirements and

can be challenging for all.

•

Prevention can be undertaken in all patients at risk by providing continuity of care; keeping familiar

persons at the bedside; limiting medication, room, and staff changes; limiting unnecessary

catheterization; and avoiding restraints.

•

Causes such as polypharmacy, opioid toxicity, urinary retention, constipation, and infection should

be ruled out.

•

For mild to moderate cases, add haloperidol.37

•

More severe terminal delirium can be managed with midazolam infusion or other forms of sedation.

•

These interventions, which in conjunction with high-dose opioids can induce "double effect" (the

outcome of hastening death when the intention is purely to relieve symptoms), require expertise

and can lead to ethical controversy.38,39

•

Consultation with a palliative care specialist is recommended when delirium, pain, or any other

symptoms appear to be intractable.

•

As mental status changes occur during the dying process, patients lose the capacity to clear upper

respiratory secretions ("death rattle").

•

Nonpharmacologic interventions, such as positioning to facilitate drainage and very gentle anterior

suctioning (not deep), are an appropriate initial response.

•

Pharmacologic interventions may include hyoscyamine (Levsin), glycopyrrolate (Robinul),

scopolamine, octreotide, and the oral use of atropine eyedrops (Table 5).40

•

Patients do not report experiencing these sounds to be as distressing as family members or

caregivers find them, and education regarding this issue may be as effective as positioning and

medication.41

•

A randomized trial is presently underway comparing the effectiveness of different strategies.

Treatment of Excessive

Respiratory Secretions

• Treatment

• Dosage

• Atropine eye drops 1%

• One to two drops orally or under the tongue;

titrate every eight hours

• Glycopyrrolate (Robunil)

• 1 mg orally or 0.2 mg subcutaneously or

intravenously every four to eight hours as needed

• Hyoscyamine (Levsin)

• 0.125 to 0.5 mg orally, under the tongue,

subcutaneously, or intravenously every four

hours as needed

• Scopolamine

• One to two patches applied topically and changed

every 48 to 72 hours