Standards of pain management - Michigan Nurses Association

advertisement

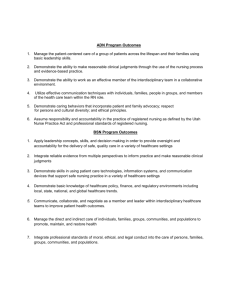

Michigan Nurses Association Debra Nault MSN, RN 2013 Expires February 2015 Purpose: This educational module will inform nurses and enhance their knowledge regarding patients’ right to effective pain/symptom management, their responsibility as healthcare providers for pain management, and the Joint Commission’s standards. Objectives: Participants will be able to: Recognize the right of patients to appropriate assessment and management of pain Identify how to screen patients for pain during their initial assessment and when ongoing, periodic re-assessments are clinically required. List three best practices and approaches to improving the quality of pain management. At a fundamental level, improving pain management is simply the right thing to do As an expression of compassion, it is a cornerstone of nursing and health care’s humanitarian mission It is just as important from a clinical standpoint, because unrelieved pain has been associated with undesirable outcomes such as delays in postoperative recovery, and development of chronic pain conditions Evidence-based pain management, one of the first Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality guidelines introduced, occurred in 1992 The guidelines are a compilation of the best available evidence, but implementation of these guidelines was voluntary The American Pain Society cited the need to ‘‘move beyond traditional education and advocacy to focus on increasing pain’s visibility in the clinical environment” In 1999, the Joint Commission approved standards for acute care pain management to be implemented in 2001 Historical under-treatment of pain among inpatients resulted in a national requirement for pain practice standards On January 1, 2001, pain management standards went into effect for Joint Commission accredited ambulatory care facilities, behavioral health care organizations, critical access hospitals, home care providers, hospitals, office-based surgery practices, and long term care providers Congress declared the decade beginning on January 1, 2001, as the “Decade of Pain Control and Research” For most accreditation programs, the pain management standards appear in the Provision of Care, Treatment and Services (PC) and the Rights and Responsibilities of the Individual (RI) chapters of The Joint Commission’s accreditation manuals. For the behavioral health care program, the pain management standards appear in the Care, Treatment and Services (CTS) chapter. “Speak Up: What you should know about pain management” is a patient education brochure that provides questions and answers to help patients talk with their doctor, nurse and other caregivers about how to treat their pain. Free downloadable files of all Speak Up brochures (including Spanish language versions) are available on The Joint Commission website at http://www.jointcommission.org/speakup.aspx. Joint Commission Resources (JCR), a not-for-profit subsidiary of The Joint Commission, offers a number of resources on pain management. For more information, visit JCR’s website, www.jcrinc.com, or request a catalog from the JCR Customer Service at (877) 223-6866. The pain management standards were developed in collaboration with the University of Wisconsin – Madison Medical School and were part of a project funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation The Joint Commission worked with a panel of pain experts to develop the standards addressing pain management Health care professionals, professional groups and associations, including the American Pain Society, consumer groups and purchasers were involved in the development of the standards The pain management standards require that patients be asked about pain, depending on the service the organization is providing There are some services that do not require a pain assessment, for example, if a patient is being x-rayed. However, if a patient is experiencing pain, appropriate care should be made available The organization’s response to a patient’s pain is based on the services it provides If screening indicates that pain exists, the organization may assess and treat the pain, assess the pain and refer the patient for treatment, or refer the patient for further assessment. Optimal pain care for hospitalized patients continues to remain elusive Results of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Survey (HCAHPS) show that only 6374% of hospitalized patients nationwide reported that their pain was well controlled (Summary of HCAHPS Survey Results, 2011) Although pain research has resulted in a better understanding of pain modalities and the development of new treatments, patients report little increase in satisfaction with the management of their pain while hospitalized (Department of Health and Human Services, 2011) Recognize the right of patients to appropriate assessment and management of pain Screen for the presence and assess the nature and intensity of pain in all patients Record/document the results of the assessment in a way that facilitates regular reassessment and follow-up Determine and ensure staff competency in pain assessment and management by providing education, and address pain assessment and management in the orientation of all new clinical staff Establish policies and procedures that support the appropriate prescribing or ordering of pain medications Ensure that pain does not interfere with a patient’s participation in rehabilitation Educate patients and their families about the importance of effective pain management Address patient needs for symptom management in the discharge planning process Incorporate pain management into performance activities (i.e., establish a means of collecting data to monitor the appropriateness and effectiveness of pain management) The hospital provides patient education and training based on each patient's needs and abilities. Important points:1) Acute care patients are discharged with instructions for self-care 2) Patient education influences the patient’s outcome and promotes healthy behaviors 3) The organization needs to assess the patient’s learning needs and use educational methods and instruction that match the patient’s level of understanding Based on the patient's condition and assessed needs, the education and training provided to the patient by the hospital include any of the following: one of these relates to pain: Discussion of pain, the risk for pain, the importance of effective pain management, the pain assessment process, and methods for pain management First, make sure your nursing practice reflects the Joint Commission’s pain management standards, national standards on pain management, your state's nurse practice act, and your facility's policies Remember that patients have the right to adequate pain assessment and management, and they rely on you to advocate for them If your care deviates from the standards, thoroughly document the reason For example, if a patient refuses pain medication, document the refusal and the reason, notify the prescriber, and request an alternative pain medication if appropriate Document the actions you take to obtain another pain medication and your patient teaching As a Person With Pain, You Have: The right to have your report of pain taken seriously and to be treated with dignity and respect by doctors, nurses, pharmacists and other healthcare professionals The right to have your pain thoroughly assessed and promptly treated The right to be informed by your doctor about what may be causing your pain, possible treatments, and the benefits, risks and costs of each The right to participate actively in decisions about how to manage your pain The right to have your pain reassessed regularly and your treatment adjusted if your pain has not been eased. The right to be referred to a pain specialist if your pain persists The right to get clear and prompt answers to your questions, take time to make decisions, and refuse a particular type of treatment if you choose Pain Care Bill of Rights, page 1 of 1 Created: 04/09 NYU PAIN CARE BILL OF RIGHTS Patient’s Rights As a person with pain, you have the right to: be treated by staff committed to pain prevention have your report of pain respectfully acknowledged by all members of your healthcare team have your pain assessed regularly and responded to quickly get clear and prompt answers, take time to make decisions, and refuse a particular type of treatment receive education on the importance of pain management and set goals for pain relief. be referred to a pain specialist if needed Patient’s Responsibilities As a patient, you are responsible for: taking an active role as a team member in reporting your pain and any related information sharing with the healthcare team, your history and experience with pain relief (with or without medication) participating in making decisions about how to manage your pain working with your healthcare team to set goals for pain relief and develop a plan asking your healthcare team what you can expect in relation to your pain asking questions sharing concerns about the plan, side effects, risk of addiction, cost, etc. Pain is one of the major reasons patients seek care However, hospitals continue to struggle with the issue According to Joint Commission officials at the 2009 Executive Briefings, pain assessment and reassessment is a top 10 most-cited standard under PC.8.10 for which hospitals received RFIs in 16% of surveys in 2007 and the first quarter of this year Poor pain management practices, poor documentation, poor practitioner knowledge Erroneous individual myths and beliefs about pain management and a critical lack of knowledge perpetuate inaccuracies and bias in pain management practice Knowledge used for pain management may reflect the same knowledge nurses learned in their basic programs In fact, younger, less experienced nurses have scored better on pain management knowledge and attitude tests Lack of organizational support Administrative priority only when patient pain satisfaction declines or fails to meet expected standards of care Lack of physician cooperation has long been identified as a barrier Lack of time, staffing, and resources The process involves complex decision making, adequate nurse-patient communication, planning, and evaluation in a busy, hectic environment Studies have also suggested a connection between unit culture and pain management practice “Many doctors seem to have a lack of concern about others’ pain. I've seen physicians perform very painful treatments without giving sedatives or pain medicine in advance, so the patient wakes up in agony. When they do order pain medicine, they're so concerned about overdosing that they often end up underdosing.” Require comprehensive initial and frequent assessments Need reliable and valid instruments along with assessment-based interventions Re-assessment, and further intervention as required Compliance with EBPM is evaluated through a review of nursing documentation The practice environment and nurses’ clinical expertise offer insight into the factors influencing the implementation The process of integrating good pain management practices into an organization’s everyday life requires a comprehensive approach that includes—and goes beyond— performance improvement to overcome barriers and to achieve fundamental system changes. Researchers and pain management experts have identified a core set of activities characterized by using an interdisciplinary approach to facilitate these system changes. Form a multidisciplinary committee of key stakeholders Identify unit-specific nursing and physician leaders as champions of pain management Analyze current pain management practice performance Make improvement through continuously evaluating performance Nursing Today! Nursing back when … Pain is population specific, varying with factors such as age, cultural diversity, and cognitive impairments It takes understanding to sense, using verbal and nonverbal communication, the level of pain a patient is experiencing, especially when he or she is ventilated or cognitively impaired, such as a patient with Alzheimer’s Pain is in the eye of the beholder – as pain management pioneer Margo McCafferey wrote in 1968, “Pain is what the patient says it is, and it’s as bad as the patient says.” Know how to educate those who are caring for a population that cannot communicate its pain The Joint Commission brochure focuses on adult pain management quite well, but does not specifically address the pediatric population With pediatric medication errors so high, it will benefit your facility to take the time to understand the pain management and pain assessment needs for children, particularly those too young to explain their own pain New Pediatric Standard for 2012 The hospital involves the family, when appropriate, in identifying signs of pain Pediatric PROCEDURAL PAIN REQUIREMENT Elements of Performance 6: In order to reduce stress and pain related to procedures, the hospital intervenes before the procedure using pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic (comfort) measures The key is knowledge -- we must educate everyone involved with the patient Nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, physical therapists, dietitians, residents, and even counselors should receive education on how to assess and manage pain in their patients Most healthcare providers do well when it is expected that the patient will experience pain, like after surgery, for example However, without cues such as an incision site, providers may forget to ask about pain It boils down to assessment and reassessment If you don’t educate staff on pain pathophysiology, they will not be able understand the entire process Policy – when it comes to pain management, an RFI can be a self-inflicted wound! Is your pain assessment and management policy too tight? Does it need to be clarified or simplified? Did staff members have input into its design? Like any policy, a pain assessment policy that is too stringent can leave your organization open to an RFI simply because it is impossible for staff members to reasonably comply with it Speak with frontline staff members Listen to how they assess pain and the steps they go through to determine the level of pain in their patients and develop an effective policy from that information There are many factors that affect pain perception including pain threshold which is described as the lowest intensity of a stimulus that causes the subject to recognize pain Another factor includes the release of endorphins by the patient which is specific to the individual Finally, pain tolerance is considered one of the key perception factors and interventions are necessary to expand the medication tolerance times The first element of the patient pain requirement is that a pain assessment is performed It must be all inclusive Relates to the care, treatment and services regarding the patient's overall condition Second, the organization needs to use appropriate means for pain assessment Must be in line with the patient’s condition and age Chronicity Severity Quality Contributing/associated factors Location/distribution or etiology of pain, if identifiable Mechanism of injury, if applicable Barriers to pain assessment The third element of performance indicates that patients should regularly reassess that patient's pain The fourth element of performance requires the health care organization treat the patient’s pain effectively Or at the very least, refer the patient to another facility for treatment Identify patients with pain in an initial “screening assessment” When pain is identified, perform a more comprehensive pain assessment, making sure to address language and/or health literacy barriers Record the results of the assessment in a way that facilitates reassessment, follow-up and data extraction for purpose of improvement Recognize the multi-dimensional nature of pain, and use a multi-disciplinary treatment, including non-pharmacologic modalities Used for neonates/infants: FLACC Assessment 0 1 2 Smiling/ expressionless Frowning Legs Normal movement/ Relaxed Restless/Tense Legs drawn up/Kicking Activity None/Lying quietly Squirming/ Tense movements Arched back/ Rigid/Jerking Cry None Occasional whimper Crying constantly/ Screaming Consolability Relaxed Easily distracted or reassured Difficult to distract/ reassure Face Clenched jaw/ Anguish Use pain management protocols and order sets, treating until patients reach target comfort levels Establish policies and procedures that support appropriate prescribing or ordering of effective pain medications Use multi-disciplinary treatment, including non-pharmacologic modalities Streamline the delivery of timely pain assessment and treatment process Pain should be reassessed after each pain management intervention, once a sufficient time has elapsed for the treatment to reach peak effect or with major change in status For example, 15 to 30 minutes after a parenteral medication and 1 hour after oral medication or a non-pharmacologic intervention Reassessment should include: 1. whether the patient's goal for pain relief was met, for example, pain intensity, effect on function (physical or psychosocial) 2. patient satisfaction with pain relief 3. whether side effects had occurred and were tolerable 1. 2. 3. Reassess and document pain relief, side effects and adverse events produced by treatment, and the impact of pain and treatment effects on patient function once sufficient time has elapsed to reach peak effect, such as 15 to 30 minutes after parenteral drug therapy or 1 hour after oral administration of a PRN (as-needed) analgesic or nonpharmacologic intervention. Reassessments may be performed less frequently for patients with chronic stable pain or for patients who have exhibited good pain control without side effects after 24 hours of stable therapy. Pain assessment for IV PCA: every 2 hours for first 8 hours, then every 4 hours; epidural or intrathecal analgesia: every 1 hour for 24 hours, then every 4 hours. Establish unit-based auditing system with effective monitoring and feedback Establish efficient institutional system of care in pain management Review mistakes and sentinel events using root cause analysis Address patient needs for symptom management in the discharge planning Ensure clinician and staff competence and expertise in pain management Educate relevant providers in pain assessment and management Promise patients a prompt response to their reports of pain All patients at risk for pain should be informed that: 1) effective pain relief is important to treatment 2) their report of pain is essential 3) staff will promptly respond to patient requests for pain treatment Patients and their families should be provided appropriate educational materials that address important aspects of pain assessment and management Percent of patients who have their pain assessed Percent of patients with severe pain No difference in all other measures by race/ethnicity/language Overall amount of opioid use Increased patient satisfaction – “How often was your pain well controlled?” “How often did the hospital staff do everything they could to help you with your pain?” Percentage of patients on opioids who have their bowel movement assessed and documented at least once per shift Unit specific average pain score Opioid analgesics rank among the drugs most frequently associated with adverse drug events Research shows that opioids such as morphine, oxycodone and methadone can slow breathing to dangerous levels, as well as cause other problems such as dizziness, nausea and falls The reasons for such adverse events include dosing errors, improper monitoring of patients and interactions with other drugs, according to The Joint Commission’s data base Reports also show that some patients, such as those who have sleep apnea, are obese or very ill, may be at higher risk for harm from opioids The Joint Commission Alert recommends that health care organizations take the following actions: Implement effective practices, such as monitoring patients who are receiving opioids on an ongoing basis, use pain management specialists or pharmacists to review pain management plans, and track opioid incidents Use available technology to improve prescribing safety of opioids such as creating alerts for dosing limits, using tall man lettering in electronic ordering systems, using a conversion support system to calculate correct dosages and using patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) Provide education and training for clinicians, staff and patients about the safe use of opioids Use standardized tools to screen patients for risk factors such as over sedation and respiratory depression Pain is an internal, subjective experience that cannot be directly observed by others or by the use of physiological markers or labs Therefore, pain assessment relies largely upon the use of self-report Much effort has been invested in testing and refining self-report methodology within the field of human pain research The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization in the United States has set standards for the assessment of pain in hospitalized patients Pain assessment should be ongoing, individualized, and documented Patients should be asked to describe their pain in terms of the following characteristics: location, radiation, mode of onset, character temporal pattern, exacerbating and relieving factors, and intensity It has been stated that the ideal pain measure should be sensitive, accurate, reliable, valid, and useful for both clinical and experimental conditions and able to separate the sensory aspects of pain from the emotional aspects McCaffey has stated that “Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing wherever they say it does.” It is the body’s signal of distress and remains one of the most common reasons people visit their physician or visit the hospital Normal pain sensations involve transmission and interpretation termed nociception The clinician must understand transduction, transmission, and perception as well as pain modulation in order to better care for the patient with pain The types of pain are also evaluated when assigning ICD-9 CM codes to properly portray the patient condition Practitioners’ personal biases about the patient’s pain may interfere with the realization of the definition when doing a pain assessment Sometimes, the intrinsic subjectivity of pain is often disregarded Practitioners who would likely not judge the character of a patient who needs increased amounts of medication to treat hypertension may believe that a patient whose persistent pain does not respond to standard medications is ‘drug-seeking,’ a narcotic abuser, or has a current need to ‘escape reality’ Acute pain: Defined as intermittent pain occurring for less than 90 days (Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines, 2009) and resulting from trauma, impact, burns, or surgery. It is abrupt, intermittent, and nociceptive. Chronic Pain: Defined as over occurring for at least 3 months by the AMA and over 6 months by the American Psychological Association. Both concur there is no active disease or unhealed tissue injury. This type of pain may be caused by faulty processing of sensory input by the nervous system. Pain interventions may be ineffective resulting in frustration, anger, and depression (Rosdahl, 2010). Somatic Pain: Defined as localized pain that becomes increasingly uncomfortable with movement and very tender when palpated. It is sometimes referred and described as, per the Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines, sharp, throbbing, shooting, pinching, and deep aching that includes bone, post-op, and muscle pain. Neuropathic Pain: Defined as difficult to cite the source of pain as it tends to follow dermatome pathways. Palpation tends to send pain to nerve endings distally. This pain is described as burning, radiating, and numbing at times with limb “heaviness.” There may be swelling, redness, and mottling with skin temperature fluctuations (Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines, 2008). Visceral Pain: Defined as constant and localized but may be referred like diaphragmatic pain refers to the right shoulder and cardiac pain which can refer to the left arm and the jaw. Cancer Pain: Defined as pain due to a malignancy which is described as very severe, chronic, and intractable causing resistance to many medications, thus long and short term analgesics are usually required to prevent “breakthrough pain) (Rosdahl, 2010). Hospice nurses are usually very skilled at pain management because of cancer pain needs. Standard: 1) a criterion established by authority or general consent as a rule for the measure of quality, value, or extent; or 2) for purposes of accreditation, a statement that defines the performance expectations, structures, or processes that must be substantially in place in a organization to enhance the quality of care Standards typically are used by accrediting bodies such as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) to evaluate health care organizations and programs Criteria: defined as a means for judging or a standard, a rule, or a principle against which something may be measured Guidelines: systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances Consensus statements and position papers: expressions of opinion or positions on health care issues generally prepared by professional societies, academies, and organizations and generated through a structured process involving expert consensus, available scientific evidence, and prevailing opinion Statute: a law created by a legislative body at the federal, state, county, or city level. Commonly called a law or an act, a single statute may consist of just one legislative act or a collection of acts Regulation: an official rule or order issued by agencies of the executive branch of government Regulations have the force of law and are intended to implement a specific statute, often to direct the conduct of those regulated by a particular agency Michigan Public Health Statute Public Health Code MSA 14.15: General Provisions 04/01/99 01/08/02 Pharmacy Board Guideline Guidelines for the Use of Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain 2005 -- Nursing Board Guideline Michigan Board of Nursing Guidelines for the Use of Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain -- -- Joint Board Guideline Michigan Guidelines for the Use of Controlled Substances for the Treatment of Pain & accompanying statement late 2003 (1) Effective for the renewal of licenses or registrations issued under this article and expiring after January 1, 1997 if the completion of continuing education is a condition for renewal, the appropriate board shall by rule require an applicant for renewal to complete an appropriate number of hours or courses in pain and symptom management. Rules promulgated by a board under section 16205(2) for continuing education in pain and symptom management shall cover both course length and content and shall take into consideration the recommendation for that health care profession by the interdisciplinary advisory committee created in section 16204a. A board shall submit the notice of public hearing for the rules as required under section 42 of the administrative procedures act of 1969, being section 24.242 of the Michigan Compiled Laws. Pain — An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage Acute Pain — Acute pain is the normal, predicted physiological response to a noxious chemical, thermal or mechanical stimulus and typically is associated with invasive procedures, trauma and disease. It is generally time-limited Chronic Pain — Chronic pain is a state in which pain persists beyond the usual course of an acute disease or healing of an injury, or that may or may not be associated with an acute or chronic pathologic process that causes continuous or intermittent pain over months or years Addiction — A primary, chronic, neuro-biologic disease, with genetic, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviors that include the following: impaired control over drug use craving, compulsive use, and continued use despite harm. Physical dependence and tolerance are normal physiological consequences of extended opioid therapy for pain and are not the same as addiction. Physical Dependence — A state of adaptation that is manifested by drug class-specific signs and symptoms that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist. Physical dependence, by itself, does not equate with addiction. Pseudoaddiction — The iatrogenic syndrome resulting from the misinterpretation of relief-seeking behaviors as though they are drug-seeking behaviors that are commonly seen with addiction. The relief-seeking behaviors resolve upon institution of effective analgesic therapy. Substance Abuse — The use of any substance(s) for non-therapeutic purposes or use of medication for purposes other than those for which it is prescribed. Tolerance — A physiologic state resulting from regular use of a drug in which an increased dosage is needed to produce a specific effect, or a reduced effect is observed with a constant dose over time. Tolerance may or may not be evident during opioid treatment and does not equate with addiction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 July; 21(7): 689-693 Joint Commission Resources. 2009 Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals: The Official Handbook. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources Inc; 2009. Strategies to Improve Pain Management – American Pain Society, www.ampainsoc.org/ education/enduring/downloads/.../ section_5.pdf Estabrooks CA, Midodzi WK, Cummings GG, Wallin L., Predicting research use in nursing organizations: a multilevel analysis. Nurs Res. 2007;56(4S):S7–S23. Van Niekerk LM, Martin F. The impact of the nurse/physician relationship on barriers encountered by nurses during pain management. Pain Manag Nurs. 2003;4(1):3–10. Bell L, Duffy A. Pain assessment and management in surgical nursing: a literature review. Br J Nurs. 2009;18(3):153–156. McClure ML, Hinshaw AS, eds. Magnet Hospitals Revisited: Attraction and Retention of Professional Nurses. Washington, DC: American Nurses Association; 2002. Clabo LML. An ethnography of pain assessment and the role of social context on two postoperative units. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61:531–539. Wild LR, Mitchell PH. Quality pain management outcomes: The power of place. Outcomes Manag Nurs Pract. 2000;4(3):136–143. This monograph was developed by JCAHO as part of a collaborative project with NPC, 3/2003 Susan J. Fetzner PhD, MBA, RN; Joanne G. Samuels PhD, RN Clinical Nurse Specialist: The Journal for Advanced Nursing Practice October 2009 Volume 23 Number 5 Pages 245 – 251 Medscape Review Pain Asessment : Stephen Kishner, MD, MHA; Chief Editor: Erik D Schraga, MD Copyright 2008 Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations 512 September 2008 Volume 34 Number 9 The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety; Debra B. Gordon, RN, MS.; Susan M. Rees, MS, RN., CPHQ.; Maureen P. McCausland, DNSc, RN.; Teresa A. Pellino, PhD, RN; Sue Sanford-Ring, MHA; Jackie Smith-Helmenstine, CPHQ; Dianne M. Danis, RN, MS American Pain Foundation. Available at http://www.painfoundation.org Bernhofer, E., (October 25, 2011) "Ethics and Pain Management in Hospitalized Patients" OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing Vol. 17 No. 1. Please remember to fill out the evaluation form. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Historically there have been no problems with pain treatment for inpatients. True or False The Joint Commission was the one entity that worked on developing pain management guidelines. True or False Some services do not require a pain assessment. True or False Since Congress declared a “Decade of Pain” in 2001, patients have reported huge increases in satisfaction with management of their pain while hospitalized. True or False According to the Joint Commissions’ standards related to pain management, healthcare providers must: a. recognize the right of patients to have an assessment of pain b. screen for its presence c. record results of the assessment d. ensure staff competency e. all of the above Joint Commission standards related to pain management include all of the following concepts but: a. policies should address appropriateness of prescribing and ordering b. addressing the need for symptom management after discharge c. importance of patient and family education d. data collection for performance measures is not necessary 7. What should be done when a patient refuses pain medication? a. nothing, it’s the patient’s right to refuse medication b. just offer an alternative pain management option c. document refusal, reason, and notify the prescriber d. educate the patient why he/she shouldn’t refuse 8. According to the “Patient Care Bill of Rights” a person with/in pain: a. shouldn’t discuss risks, benefits or cost of pain medication b. is usually too sick to participate in decisions about pain management c. can’t refuse a type of treatment for pain if it’s recommended d. can be referred to a pain specialist if their pain persists 9. A major barrier to good pain management practice includes: a. physicians often perform treatments with too much pain medication b. nurses know too many different methods of pain management c. it’s consistently the priority of many administrations d. lack of time, staffing, and resources 10. Included in evidenced based practice related to pain management guidelines: a. all you need is a good performance improvements process b. any instrument to measure pain is acceptable c. compliance is evaluated through review of nursing documentation d. all of the above 11. The main focus of the new Pediatric Standard for 2012 includes: a. pediatric procedural pain requirement b. nursing expertise and not utilizing family bias c. one valid pediatric pain scale for universal use d. intervening during a painful procedure 12. Many factors affect pain perception and necessary interventions: a. pain threshold b. release of endorphins c. pain tolerance d. all of the above 13. Concepts in a multidimensional approach to pain management include: a. only need to identify etiology, or mechanism of injury b. assessing chronicity or acuteness of pain c. assessment and reassessment d. chronicity, severity, quality, contributing factors, location & etiology 14. Pain should be reassessed: a. after each pain management intervention b. once a sufficient time has elapsed for treatment to reach peak affect c. with a major change in the patients’ status d. all of the above 15. Reassessment should include: a. only a pain scale and vital signs b. if the ordering physician’s goal was met for treatment c. whether side effects occurred and were tolerable d. none of the above 16. Actual pain is rarely population specific and varies little with age, cultural diversity or cognitive impairments. True or False 17. When discussing pain which of the following statements is true? a. Abnormal pain sensations involve transmission and interpretation termed “nocioception” b. Clinicians just need to understand pain perception to care for patients c. Pain is so diverse assigning ICD-9 codes is impossible d. Pain is the body’s signal of distress 18. Match the type of pain with its definition: a. acute a. pain due to malignancy b. chronic b. difficult to cite source, tends to follow dermatome pathways c. somatic c. no active disease or unhealed injury d. neuropathic d. intermittent, abrupt, and < 90 days e. visceral e. localized that becomes uncomfortable with movement and tender with palpation f. cancer f. constant & localized, may be referred 19. By definition physical dependence equates with addiction. True or false 20. By definition tolerance is: a. always equated with addiction b. always a psychological state resulting from opioid treatment c. a physiological state resulting form regular use of a drug in which an increased dose is needed to produce a specific effect d. nurses obtaining a CE on pain year after year