Party identification was once supposed to be a

advertisement

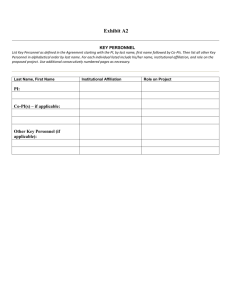

THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 1 Through the Party Lens. How Citizens Evaluate TV Electoral Spots Christina Holtz-Bacha Bengt Johansson Paper submitted to the International Communication Conference (ICA), Phoenix, Arizona, 2012 THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 2 Abstract Party affiliation is considered as one of the most important factors explaining voter’s party choice, but also a strong intervening variable when it comes to the effectiveness of electoral advertising. The question raised in this study is to what extent party affiliation explains voters judgments of electoral advertising, which was investigated by using panel data carried out during the Swedish general election campaign 2010. The results show that party affiliation still functions as a filter when voters are exposed to electoral advertising. The findings are suggested to be understood against the background of cognitive dissonance theory and selective exposure according to which people try to avoid a state of cognitive dissonance by avoiding information that conflicts with their attitudes. KEYWORDS: ADVERTISMENT, PARTY AFFILIATION, ELECTION CAMPAIGNS THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 3 Through the Party Lens. How Citizens Evaluate TV Electoral Spots Party identification was once supposed to be a stable factor in the decision making process during election campaigns. The so-called Michigan or Ann Arbor model (Campbell, Gurin & Miller, 1954) put party identification at the entrance of the funnel of causality leading to the voting decision and thus influencing the other variables in this process. Party identification was also identified as a shortcut (Popkin, 1994, pp. 50-53) sparing voters the task of seeking information as a basis for their electoral choice. In addition, when exposed to campaign information, party identification served as a predisposition guiding the audience in their selection process making people preferably turn to information that reinforces their attitudes (Lazarsfeld, Berelson, & Gaudet, 1948). However, the Western democracies have experienced an erosion of party identification during the last decades leading Dalton (2002) to speak of a dealignment process. Dealignment means that more and more citizens lose their traditional party ties which had long been a strong predictor of the vote. Instead, voters base their voting decision on short term factors making them also more prone to change their mind from one election to the other or even during the course of the election campaign. The new instability of the vote is also indicated by the fact that the percentage of late deciders increases. In Sweden, the country that this study refers to, partisanship has drastically decreased since the end of the 1960s. While 65 percent of the electorate identified with a party in 1968, only 31 percent said they felt close to a party in 2006 and only 15 percent showed strong party ties. Another aspect of weakening ties between parties and the voters is the rising amount of floating voters. In the beginning of the 1960's 11 percent changed party between elections, and the corresponding figure in 2006 was 37 percent (Oscarsson & Holmberg, 2008, p. 25). Without the 'protective shield' of party identification and voters now being more 'open' for switching allegiances, they should also be more susceptible to campaign messages. If that THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 4 is the case, campaigns are important and campaigners are well advised to make efforts for mobilizing and convincing the electorate: Much can be gained in an election campaign, but much can be lost as well (Holtz-Bacha, 1999, p. 11). Against this background, this paper seeks to assess to what extent party identification still works as a filter when people are exposed to campaign advertising. Since previous research has found party affiliation to be a strong intervening variable when it comes to the effectiveness of electoral advertising, the question is whether that is still the case or whether the weakening party ties have indeed brought up a new openness of voters towards party advertising and thus increased chances for its persuasive power. Previous Research Early research on the effects of electoral advertising on television suggested that the spots could overcome the barrier set up by low interest and partisan selectivity particularly due to the impossibility to avoid the advertising (Atkin, Bowen, Nayman, & Sheinkopf, 1973). Compared to other campaign material, TV spots were therefore regarded as a superior channel to reach voters. Joslyn (1981) attributed to electoral ads a major influence on partisan defections (defined as votes cast contrary to one's partisan identification) and thus supported the view that these broadcasts can overcome party identification. Later research using party identification as a control variable, however, concluded that the group of voters most likely to be influenced by campaign advertising on television would be the independents and weak identifiers (e.g., Ansolabehere & Iyengar, 1995). A more recent study by Franz and Ridout (2007) yielded inconsistent effects of partisanship and showed that ads, contrary to the researchers' expectations, did not have their greatest effects on independents and viewers with weak attachments but also affected strong Democrats. THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 5 In particular, party identification has demonstrated its influence on the mobilizing and persuasive effects of negative advertising. Ansolabehere and Iyengar (1995) established that attack ads are likely to decrease turnout among independents and tend to reinforce the support of partisans for their candidate. They also found Republicans to be the least affected in their turnout. This finding was supported by Franz and Ridout's (2007) general assessment that Republicans seem to be more immune to the appeals of electoral advertising but was challenged by Lemert, Wanta and Lee (1999) who found effects of negative advertising on partisans of both parties. In contrast to Ansolabehere and Iyengar (1995), Jackson, Mondak and Huckfeldt ascertained that "[e]xposure to negative political ads apparently does not have especially problematic consequences for the attitudes of either non-partisans or the politically unsophisticated" (2009, p. 63). A meta-analysis of research on the effects of negative campaigning found some support for the stimulation of turnout among partisans and the likelihood of independents being turned off but also pointed to the weak evidence due to the small number of studies (Lau, Sigelman, & Rovner, 2007). All in all, the findings of extant research on the potential of electoral TV ads to overcome partisan selectivity are mixed. In addition, due to the long tradition of electoral advertising on television and the paramount importance of the ads in U.S. campaigns, most of the studies on their effects were done in the United States. Parties do not play the same role in the U.S. as for instance in the European countries where, irrespective of an increasing focus on candidates, parties still dominate the political process. However, the erosion of partisanship over the last decades has been a phenomenon that became visible throughout the Western world (Dalton, 2002). Parties lost their loyal base, party ties got weaker and votes became more unpredictable. This development seems to speak for increasing possibilities for campaign advertising to influence voters while on the other hand the protective shield of partisanship should get porous. Nevertheless, in an overview on THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 6 political communication and campaign effects, Iyengar and Simon concluded: "Party identification remains the salient feature of the American electoral landscape" (2000, p. 159). Therefore, this paper sets out to study the effectiveness of party identification as an intervening variable in the reception of party advertising in a European context. Based on what was said before about party affiliation, the research question of this paper is: To what extent does party affiliation explain how electoral advertising is judged by the audience? Electoral Advertising on Swedish Television Until now, political advertising has played a limited role in Swedish political campaign culture. Instead media, controlled by journalists, has been seen as more important. The socalled free media, news casts on television, newspapers and journalistic interviews and debates, were believed to be more effective and significant compared to political advertising (Petersson, Djerf-Pierre, Strömbäck, & Weibull, 2006). These attitudes should be understood in relation to Swedish regulations of electoral advertising on television. TV ads were prohibited before the digitalization of terrestrial television in 2005, and political advertising was therefore not broadcast on major channels until the European parliament election 2009 and the Swedish general election 2010. The election in 2010 can be seen as the breakthrough for electoral advertising on television, since all major parties purchased airtime on the commercial channel TV4 during the last weeks of the campaign (Grusell & Nord, 2010). Even if there was a code of conduct between the broadcaster (TV4) and the political parties in the 2010 campaign, the legal regulations are few. The ads only have to observe the law, which mostly refers to criminal law and facts like incitement to racial hatred or violence. Further, there are no legal limitations for the amount of airtime possible to purchase in order to broadcast political advertising, and there is no announcement before or after the spot is aired. The spots are also broadcast in-between other commercials; there is no block where THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 7 political ads are aired exclusively. All in all, due to these conditions TV viewers are rather caught by surprise and cannot easily avoid the spots. It is no exaggeration to argue that electoral advertising has changed the Swedish campaign culture. Results showed that exposure to TV ads during the European election campaign had a significant and positive effect on voter turnout (Dahlberg, 2010) and the political parties have changed their way of campaigning in relation to this new campaign channel (Grusell & Nord, 2009). The parties spent approximately two million Euros on producing and purchasing airtime for television ads in the 2010 campaign and 69 percent of the electorate watched at least one commercial during the 2010 campaign (Oscarsson & Holmberg, forthcoming). The corresponding figure during the European parliament campaign was 66 percent (Oscarsson & Holmberg, 2010, p. 26). An intense debate took off the last weeks of the campaign when TV4 refused to air the spot produced by the Sweden Democrats, claiming it was violating the Radio and Television Act which is regulating television broadcasting. After removing some parts of the spot it was broadcast, but the complete version had then more than 500.000 clicks on YouTube. Method The method used to analyze the effectiveness of party affiliation as an intervening variable in the evaluation of party advertising was panel data collected using The 2010 Internet Campaign panel (E-panel). It is a six wave study of self-recruited respondents, which was carried out during the Swedish general election campaign in September 2010. Data was collected during a five week period (August 24 to September 30) and during this intense part of the campaign four pre-election web questionnaires and one post-election were sent out to 15.143 respondents. The respondents were recruited from various sources. Different web-sites THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 8 at the University of Gothenburg were used such as the Multidisciplinary Research Opinion and Democracy Group (MOD), The Elections Study Program and the SOM-Institute (Society, Opinion, Media). During the same period, editors for Swedish local newspapers were contacted to allow advertizing for recruitment to the panel on their web-site. Eleven Swedish newspapers agreed to take part in the recruitment process. Other sources used were two webbased party sympathy simulators constructed by researchers at the University of Gothenburg. These simulators could be used through Facebook and the Public Service Radio web-site. Social media web-sites were also used to recruit respondents (Dahlberg, Lindholm, Lundmark, Oscarsson, & Åsbrink, 2010). In order to avoid drop-outs caused by too long questionnaires combined with the need to measure specific campaign exposures, the sample was randomized into five equal sized groups. These groups received a weekly questionnaire (Monday to Friday) during a five week period. To shorten the questionnaire for each respondent randomization was used to construct each individual's questionnaire. This was done for each group of questions and each spot was shown to approximately 400 respondents. Due to the recruitment process there are deviations in the E-panel compared to the Swedish population. Tests show bias in gender, since there are fewer women compared to men in the panel and the proportion of men and women is equal in the Swedish population as a whole. But the E-panel respondents are also younger and more interested in politics compared to the general public (Dahlberg, Lindholm, Lundmark, Oscarsson, & Åsbrink, 2010). This bias must of course be taken into consideration when the data is analyzed. However, the purpose of the paper is not to study the representativeness of evaluations of the spots. Instead we aim to analyze how and in what way party identification explains perceptions of electoral advertising. The use of the E-panel is therefore equal to an experiment and not a traditional survey based on a representative sample. THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 9 The spots All spots were 30 seconds and shown to respondents in the middle of the survey, after questions about election promises and which message the respondents related to different parties. After the spot was shown the respondents answered a question controlling the ability to watch the spot in the web-survey. Thereafter a question followed asking the respondents to answer if they had seen the ad before (television, internet etc.). The last question on the theme contained a number of claims about the broadcast; if the ad was considered professionally produced, entertaining, whether it communicates the message of the party effectively, arouses strong emotions, gives a positive image of the party and if it is believed to convince people to vote for the party. All these items could be answered on a scale ranging from 0 (totally disagree) to 10 (totally agree). No opinion was also an alternative. Below follows a short presentation of the themes in the spots analyzed in the paper. Eight spots were shown in the E-panel. Only six are included in the following analysis because two spots from the Moderate Party and the Folkpartiet the Liberalsi were shown to the respondents. Christian Democrats – a More Human Sweden In the beginning of the spot a number of rapid clips show violence, loneliness and no empathy, all in dark lighting. A gang starting to beat someone lying down, a prostitute talking to a customer in a car, a girl sitting afraid on a public toilet and an old woman falling on the street but no one cares. The music accompanying these scenes is "The lion sleeps tonight" by the Tokens. Later on there are cross-cuts between a lion hunting down a zebra, vultures pecking a cadaver and the scenes described above. The spots ends with the text: "We want a THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 10 more human Sweden". Signed by the name of the party and the wind anemone, which is the party symbol. Green Party – Modernize Sweden As most parties the Green Party uses a montage of different short scenes accompanied by pop music with a slogan interpreting what we have seen. In the Green Party ad we watch a girl recycling her broken doll, a man in a suit waiting for the bus, an old lady throwing bottles in the recycle bin and a girl entering a meeting bringing her cycle-helmet. In the end a voiceover from party leader Maria Wetterstrand is heard saying: "There are a lot of people working for a better environment. It's about time we get a government doing the same". The spot ends with a picture showing the name of the party and the slogan they used during the campaign: "Modernize Sweden". Folkpartiet the Liberals – Nuclear Power This is the only party not using any music, but industrial noise is used as a rhythm-track in the spot. Fast clips showing workers pushing buttons, putting the time card in the stamp clock, machines moving, a forklift driving etc. In the end one hears the voice of party leader Jan Björklund declaring: "Almost half of all electricity in Sweden is produced by Swedish nuclear power. Keep nuclear power and we will keep the jobs". The last words can also be seen against a backdrop of smiling men and women in working clothes and helmets and the Liberals' party symbol, the corn flower, appears. Moderaterna Party – Love at Work The movie shows a number of fast-changing scenes with men and women showing interest in people they meet in work-related situations, mostly by smiles and occasional eye- THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 11 contact. The soundtrack is the 1990s rock-ballad "I wanna know what love is" by Foreigner and the spot ends with the slogan "Love at work. Just one reason why people should have a job". The last picture shows the logo of the party. Social Democrats – We Can't Wait The spot contains a number of scenes where young people are pictured as unemployed and not wanted; everyone leaves at a meeting, but a girl remains eating breakfast, fire-men are leaving on a mission and a young man is dressing slower and left behind etc. The music is fast, cheerful but also stressful in a silent-movie style. The slogan in the end says: "207 000 young people would like to join up. We can't wait". This last sentence is signed by the party symbol: the rose. Sweden Democrats – Immigration or Pension? The movie starts with a counter showing spending in state budget and two clerks sitting at a desk. A voice-over claims that "politics is about choice and priorities". Suddenly the counter stops and an alarm sounds. Thereafter the viewer sees the signs at the desks of the clerks. One says immigration officer and the other pension officer. Then appears an old woman with a walking chair slowly walking up to the desk, but she is followed by a group of burqa-dressed women with baby carriages running to pass her. Two emergency brake handles are seen and the old woman and the group of women reach for the handles. The voice-over says: "On September 19th you have the choice between immigration or pension, vote for the Sweden Democrats". The last picture shows a sign with the name of the party, the slogan "security and tradition" and a blue anemone, which is the party symbol. The spots described above are in many ways similar, but there are differences too. They are alike in terms of length (30 seconds). When spoken words are used it is voice-over to THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 12 emphasize and explain what is shown in the spot. All spots employ the technique of fast clips and music except one which used different sounds creating a rhythm. The narration is also similar since they all, except for the Swedish Democratic spot, start with fast clips, the explanation following at the end, by inserts or by text combined with voice-over. Like the pack-shot at the end of commercials, all parties show their name or party symbol in the end of the spot to remind voters who was responsible for the spot. But as mentioned above we do find differences too. The most striking one is the use of humor and the attempt to arouse emotions. There are no jokes or slapstick in the spots, but the Moderaterna Party slogan can be seen as an amusing twist. The Social Democratic ad with the cheerful music has elements of humor, but since the message of alienation and unemployment is proclaimed the smile gets stuck in the throat. The spots of the Christian Democrats and of the Sweden Democrats are clearly intended to arouse emotions. The analogy between animals eating and killing each other and the scenes of a gang beating a person in the Christian Democratic spot is effective in arousing emotions. The same can be said about the race between the old woman and the group of burqa-dressed women. In terms of negative campaigning, the ads of the political opposition (Social Democrats, Swedish Green Party and the Sweden Democrats) can be interpreted as attacking their opponents. The Christian Democratic spot has a negative tone, but is not aimed at anyone and should be considered as an attack on society as a whole, not a single party or government since the party is a partner in the incumbent government. Does Party Affiliation Make a Difference? Multiple regression analysis was applied to determine the independent influence of party affiliation on the evaluation of the individual party ads while controlling for sociodemographic variables that may be important for political opinion formation (gender, age, THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 13 education). The party affiliation variable is based on the question of which party the respondent declares s/he would vote for, excluding those who were not yet allowed to vote (under 18), don't knows and those who said they would not vote at all. The six evaluation items were combined in an additive scale with Cronbach's alpha ranging from around .90 (Christian Democrats, Folkpartiet the Liberals, Green Party , Social Democrats, Moderaterna Party) to .71 (Sweden Democrats) for the different spots/parties. The scale thus demonstrates a very good consistence and a better performance than the individual items. In a first step, Table 1 gives an overview of the spot evaluation according to party affiliation. It presents the means for the individual items demonstrating that those respondents who declared being close to the Moderaterna Party accorded the spot broadcast by their preferred party the highest rankings on three out of six items. In particular, they assessed the spot as being professionally produced, entertaining and presenting a positive image of the party. The followers of the Sweden Democrats, however, gave the highest marks to their party's spot on the items emphasizing that it was communicating the party message effectively, that it would be able to arouse strong feelings and were convinced that the spot would convince more voters to cast their vote for the party. On the other hand, the adherents of the Sweden Democrats found the spot the least entertaining and not much qualified to convey a positive image of the party. THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 14 Table 1 Evaluation of the Electoral Spots by Respondent With Party Affiliation (mean scores) The spot is professionally produced The spot is entertaining The spot communicates the message of the party effectively The spot arouses strong emotions The spot presents a positive image of the party The spot will convince more voters to vote for the party N Christian Folkpartiet Democrats the Liberals 7.08 7.32 Green Party Moderaterna Social Party Democrats Sweden Democrats 7.16 8.10 7.49 6.26 4.68 4.46 5.17 6.06 4.98 3.15 4.95 6.51 6.81 5.56 5.71 8.47 6.87 4.56 4.14 5.01 4.14 8.18 4.32 5.16 6.36 6.38 5.35 2.79 3.89 4.49 4.58 4.67 4.36 4.73 19 47 57 93 64 26 Note: Each item was rated on a scale ranging from 0=disagree to 10=agree Bivariate correlations (Pearson's R) for the six evaluation statements and the control variables were mostly significant with some differences for the individual spots/parties. For instance, while gender and age proved to be highly significant in the evaluation of the Social Democratic spot, education was only significant for the production item. In the evaluation of the Moderaterna Party spot, however, education and age were significant but gender did not play any role in the rating. Age was the only socio-demographic variable that was significantly correlated with some of the evaluations of the Christian Democratic spot. For the other parties, the picture was mixed with gender, age and education being variably significant THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 15 for some of the items. Across the board, the party affiliation variable showed highly significant bivariate correlations with most of the individual evaluation items and all spots. Multiple regression analysis was used to assess the influence of party affiliation on the evaluation of the electoral broadcasts while simultaneously controlling for the sociodemographic variables. Table 2 presents the standardized beta coefficients for the regressions on the combined evaluation scale. For all parties and spots the coefficients for party affiliation are highly significant demonstrating the strong influence of the variable on the evaluation of the party broadcasts. Controlling for socio-demographic variables hardly weakened the impact of party affiliation confirming the independent role of the variable. At the same time, if at all, gender, age and educational level affect the evaluation of the spots differently not taking out much of the explanatory power from party affiliation. Table 2 Evaluation of the Electoral Spots (beta coefficients) Party Christian Democrats Folkpartiet the Liberals Green Party Moderaterna Party Social Democrats Sweden Democrats Gender .04 .13 -.14 * .03 -.15 ** .09 Age -.25 -.12 -.23 -.25 -.24 -.23 ** ** ** ** ** Education .04 .10 .10 * .16 ** .01 -.01 PA .25 .15 .18 .27 .29 .32 ** ** ** ** ** ** R² 12% 7% 16% 17% 17% 16% N 357 337 344 333 364 381 Note: PA = party affiliation. ** significant ≤ .01, * significant ≤ .05 The explanatory power of the models, using R² as a measure, is 16 to 17 percent for all parties except the Christian Democrat model (12%) and the Folkpartiet the Liberals model (7%). Which level of explained variance can be tolerated is hard to determine, since it always has to be put in relation to what is expected and numbers of independent variables included in the model. However, the R² clearly indicate that party affiliation and the age of the respondents THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 16 are especially important to understand why people evaluate political advertising in different ways. Conclusions Even though long-term data show that party identification is on decline in Sweden, party affiliation still functions as a filter when voters are exposed to electoral advertising. Party affiliation correlates with a strong positive evaluation of the party's advertising. The decision to vote for a specific party goes hand in hand with regarding this party's spot more professional, more entertaining, as communicating the message effectively and arouse strong feelings, as presenting a positive image of the party and suited to convince other people to vote for that party. Since the questions were asked only once, no comparisons over time are available. Therefore, the beta values only indicate the correlation but not the direction in the sense of cause and effect. However, plausibility speaks for the filter being built up with the voting decision and this to precede the positive evaluation of the television advertising. The clear outcome of the analysis is the more convincing in view of the fact that this study had to use an indicator that does not represent the persistent partisanship as conceived in the concept of party identification. The variable included in this analysis captures respondents who have a long-term identification with a party but also one-time voters who may not have the stable affiliation with their presently preferred party. This variable thus actually provides for a stronger test of the influence of party affiliation and the findings show that even under the condition of only a short-term partisanship party affiliation works. Party affiliation contributes to the explanatory power independently and in addition to the socio-demographic variables that are known to influence political communication. These findings can be understood against the background of the cognitive dissonance theory and selective exposure according to which people try to avoid a state of cognitive THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 17 dissonance by avoiding information that conflicts with their attitudes (Festinger, 1962). Once people have made a voting decision and feel close to a party, even if only for one election, they tend to bolster their decision by regarding their party's advertising as professional and working in favor of the party image. The message for the parties following from these findings is only partly bad: The findings do not support the hopes that were raised by early research expecting TV ads to overcome partisan selectivity. Their advertising might work with undecided voters who have not yet made up their mind and thus do not apply the party affiliation filter but it will be difficult to convince those who have already made their voting decision. Nevertheless, the good evaluations of the party advertising by partisans could serve to mobilize these voters and make sure they actually cast their vote on Election Day which would be an important function as well in times of decreasing turnout rates. THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 18 References Ansolabehere, S., & Iyengar, S. (1995). Going negative: How political advertising shrinks and polarizes the electorate. New York: Free Press. Atkin, C. K., Bowen, L., Nayman, O. B., & Sheinkopf, K. G. (1973). Quality versus quantity in televised political ads. Public Opinion Quarterly, 37, 209-224. Campbell, A., Gurin, G., & Miller, W. E. (1954). The voter decides. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson and Co. Dahlberg, S. (2010). Premiär för TV-reklam. In Oscarsson, H., & Holmberg, S. (Eds.),Väljarbeteende i Europaval. Göteborgs universitet: Statsvetenskapliga institutionen. Dahlberg, S., Lindholm, H., Lundmark, S.,Oscarsson, H. & Åsbrink, R. (2010). The 2010 Internet Campaign panel. Gothenburg: The Multidisciplinary Research on Opinion and Democracy (MOD) Group. 3. Dalton, R. J. (2002). Citizen politics. Public opinion and political parties in advanced industrial democracies (3rd edition). New York: Chatham House. Festinger, L. (1962). Cognitive dissonance. San Francisco, CA: Freeman. Franz, M. M., & Ridout, T. N. (2007). Does political advertising persuade? Political Behavior, 29, 465-491. Grusell, M., & Nord, L. (2010). More cold case than hot spot. A study of public opinion on political advertising in Swedish television. Nordicom Review, 31(2), 95-111. Grusell, M., & Nord, L. (2009). Syftet är alltid att få spinn. Sundsvall: Demokratiinstitutet. Holtz-Bacha, C. (1999). Bundestagswahlkampf 1998 ‒ Modernisierung und THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 19 Professionalisierung. In C. Holtz-Bacha (Ed.), Wahlkampf in den Medien ‒ Wahlkampf mit den Medien (pp. 9-23). Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag. Iyengar, S., & Simon, A. F. (2000). New perspectives and evidence on political communication and campaign effects. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 149-169. Jackson, R. A., Mondak, J. T., & Huckfeldt, R. (2009). Examining the possible corrosive impact of negative advertising on citizens' attitudes toward politics. Political Research Quarterly, 62, 55-69. Joslyn, R. A. (1981). The impact of campaign spot advertising on voting defections. Human Communication Research, 7, 347-360. Lau, R. R., Sigelman, L., & Rovner I. B. (2007). The effects of negative political campaigns: A meta-analytic reassessment. The Journal of Politics, 69, 1176-1209. Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B., & Gaudet, H. (1948). The people's choice: How the voter makes up his mind in a presidential campaign (2nd edition). New York: Columbia University Press. Lemert, J. B., Wanta, W., & Lee, T.-T. (1999). Party identification and negative advertising in a U.S. Senate election. Journal of Communication, 49(1), 123-134. Oscarsson, H., & Holmberg, S. (2008). Regeringsskifte. Väljarna och valet 2006. Stockholm: Norstedts. Oscarsson, H., & Holmberg, S. (2010). Den goda valrörelsen. In Oscarsson, H., & Holmberg, S. (Eds.), Väljarbeteende i Europaval. Göteborgs universitet: Statsvetenskapliga institutionen. Oscarsson, H., & Holmberg, S. (forthcoming). NO TITLE. Redogörelse för 2010 års valundersökning. Stockholm: SCB. Popkin, S. (1991). The reasoning voter. Communication and persuasion in presidential campaigns. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 20 Petersson, O., Djerf-Pierre, M., Strömbäck, Weibull, L. (2006). Media and elections in Sweden. Stockholm: SNS Förslag. i The translation of the Swedish names of the parties is as follows; Christian Democrats (kristdemokraterna), Folkpartiet the Liberals (folkpartiet liberalerna), Green Party (Miljöpartiet – de gröna), Moderaterna Party (nya moderaterna), Social Democrats (socialdemokraterna), Sweden Democrats (sverigedemokraterna) THROUGH THE PARTY LENS 21