Interviewing, Attribution, Use of Quotes

advertisement

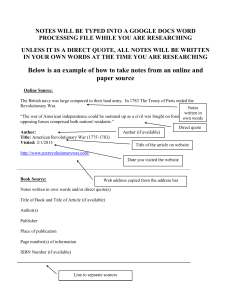

The Art of Note-taking and Interviewing The road to becoming an information gatherer “Dare to be stupid” “A motto I always try to live by is ‘dare to be stupid.’ Too many young journalists want to impress their sources with what they know. But the name of the game isn’t impressing sources, it’s getting information. The best way to do that is to profess ignorance and ask your source to educate you. It also has several side benefits. One, it eliminates the arrogant reporter stereotype and drives home the point that you are there to hear what the source has to say. Second, people are much more willing to give information if they think they’re helping out someone who doesn’t understand something. I have found this technique works whether I’m dealing with cattle ranchers or CEOs. I try to never come off as condescending in an interview, which may sound funny coming from a columnist.” -- Loren Steffy, business columnist for the Houston Chronicle “The great stories, … I have held, always come from letting someone tell a story and being there to listen. But I think reporters increasingly are not good listeners. “I think (the Watergate stories) show that the process of reporting is piecing together what so-and-so says and then somebody else, and then going back again. “The bottom line is that you don’t understand what is going on by doing a little interview with a couple of people. You really have to dig.” Bob Woodward, Washington Post THE ART OF INTERVIEWING Writing for a communications medium is basically a two-step process. ▀ The information-gathering stage (from a variety of sources) ▀ The presentation stage Both steps require preparation and thoughtful consideration. Information gathering Using our metaphor about building a “writing house,” information is akin to the utilities (water, gas, electricity) and cable; you almost never generate those yourself. Where does information come from? Here are some sources: Polls Surveys Medical and scientific research Government records Events (games, debates, concerts) Archival sources (libraries, Internet) Interviews (your notes) Note-taking Page 74 of your textbook has a great illustration of what a typical reporter’s notebook might look like after an interview. For filing purposes, it’s good to log the time, date, place etc. that the notes were made. Basically, there are three types of note-taking, and they each have their advantages and disadvantages: Notebook: Or a cocktail napkin. Cheap, no batteries. Slow? Illegible? (Don’t use a felt tip pen to cover a hurricane or rainstorm) Tape recorder: Accurate, allows easy posting to the Web. But machines break, tapes cost money. Note that Texas is a one-party consent state for tape-recording. Typing: Faster note-taking – if you can type. Allows cut-and-paste for a story. Machines break, files don’t save Source-Reporter Relationships Points from a Poynter Institute seminar session moderated by Deborah Potter, formerly of CBS and CNN and now a contributor to American Journalism Review: Many sources are clueless when it comes to reporter-speak. New shades of gray have developed (the Connie Chung "just whisper it to me" interview with Newt Gingrich's mom is an example) Because reporters often have to form "contracts" of sorts with sources in order to gain access to information, it is critical that all sides understand the language within these interpersonal contracts. It is the responsibility of the journalist to ensure that the rules of the game are understood. Rules of the game: 1) Will the source allow the use of their name or is indirect identification preferred? Is a generic descriptor needed? (“A high-level Pentagon official said … ”). 2) Have you defined the terms within the “contract”? a) On the record -- Identification of the source and all information obtained can be used b) Background -- The information is not for direct attribution, but is usable for quotation, etc. You have to decide how the source will be identified. (“This new school dress code policy will be impossible to afford,” said one parent.) Rules of the game: c) Deep background -- No attribution and no quotes can be used, but the information can be used for explanation, context, etc. d) Off the record -- No information will be used. e) Confidentiality -- The identity of the source will never be revealed. f) Anonymity -- The identity of the source will protected except in the case of a lawsuit. Shield laws help here. g) Embargo -- An agreed upon length of time between when the information is obtained and when it is published. (Woodward / Ford interview on Iraq etc.) Rules of the game: 3) Should you inform an off-the-record source that you are looking elsewhere for confirmation? 4) Will you allow a source to go off the record retroactively? Can you tell the story accurately without that information and minimize harm? 5) How many anonymous sources can be used before going with a story? (Potter said two; Chronicle policy is three. Both insist that the editor be told who the sources are.) 6) Be aware of the source's agenda -- if any. SOURCE/REPORTER RELATIONSHIPS: BE TRUSTED OR BETRAYED? A CHECKLIST TO SAVE YOU SOURCE/REPORTER RELATIONSHIPS: ATTRIBUTION: Whose responsibility IS it to define and explain the terms that are used -- not for attribution. Background, deep background, off the record? Should news organizations have a clear procedure (including approval by higher-ups) for granting anonymous sources? Should sources of information who are not being named be described whenever possible? SOURCE / REPORTER RELATIONSHIPS: CONFIRMATION: Should there be a clear policy on when information accepted on a not-for-attribution basis can be used without corroboration from a second source? Can documentary evidence been considered a second source when it is provided by the first source? (the CBS story on Bush’s National Guard duties) Under what circumstances should information from another news organization be reported? SOURCE / REPORTER RELATIONSHIPS: EMBARGOES: Under what circumstances should information be accepted on an embargoed (hold for release until some future date) basis? Is it ever ethical to break an embargo which has been agreed to? SOURCE/REPORTER RELATIONSHIPS: FRIENDSHIP: How do you keep from trading independence for access? Can the disclosure of payments or other special relationships with sources justify their use or existence? Don’t look a gift source in the mouth ISSUES What constitutes a gift? Is there a difference between a movie ticket and a plane ticket? If it doesn't involve your beat, is it OK to accept a gift? Does the value of the gift make a difference in whether you accept it? Sir Winston Churchill, at a dinner party, uttered a famed observation about ethics and accepting “gifts.” (Sir Winston … what kind of woman do you think I am?” Don’t look a gift source in the mouth CHECKLIST Does the gift-giver expect anything -- directly or indirectly? What would your reader or viewer think if you announced you'd received a gift? Would you be willing to explain what you accepted and why you did so? Are you getting the gift only because of your position? Can you work out a way to pay your own way? If not, should you accept it? Don’t look a gift source in the mouth ALTERNATIVES TO ACCEPTING A GIFT Refuse it / return it with a letter explaining why you can't accept it and keep a copy of the letter for yourself and your supervisor Pay for it Donate it to charity Keep the gift, but donate its value in cash to a charity Getting ready for the interview Front-end thinking needed Types of interviews Long, formal sitdown: You have many questions, need to confront the subject face to face Quick phoners: Just need a few facts Walkaround: Touring the scene, getting lay of the land On the fly chat (interviewing a coach at halftime as they head to the locker room) Backgrounder: Talking to experts to educate yourself, get context, perhaps not even for attribution Note the advantages and disadvantages (Page 76) of doing interviews in person, by phone or by email or letter How to do an interview How you conduct an interview – in length, tone, equipment needed -- and how many interviews you do, is often shaped by the medium that you are working for and by what type of story you are doing. Since you will likely be working at a “convergence of skills” medium, you may have Web, print and broadcast obligations all on the same story. The type and style of interview(s) you do may vary from medium to medium. A closer look at the mediums and types of stories … Mediums Print journalists often need description and explanation, so they want plenty of details. Their stories aren’t measured by a time clock. Journalists who write for the Web don’t have to worry about space as much. Broadcast (and Web video) journalists have the advantage of video to fill in details, and because they are up against a clock, they prefer briefer interviews -- the quick hit, the “sound bite.” PR writers need information suitable for company newsletters, a company magazine, annual reports or news releases. One advantage for PR writers -- their sources generally WANT (or are required) to give them information. Types of stories (non-opinion) News story -- The writer pays more attention to the background clips or current pertinent information about a source rather than the source’s personality. Can be a one-source story. News features and profiles -- The writer elevates the personality, interests and environment of the source rather than looking for a news peg. Timeliness is not as big a factor. Often requires multiple sources. Investigative pieces -- The writer needs to know both the subject matter and the source, so many interviews and much research may be required. Type of story It is helpful, especially with longer, more complex stories, to try to visualize how you think the story will / should take shape even before you begin interviewing. Think of the story as a skeleton -- the information you gather is the flesh that fills it out. This will help you determine who to talk to and what questions to ask. Apply this process to the profile you will do – you have a general idea why you chose your subject. Who do you interview to get a well-rounded view of him/her? Is there an anecdote or quote you have in mind for your intro / lead? Before the interview A CHECKLIST Getting started: A 4-PART PROCESS Educate yourself on the subject matter Interview requests Prep work after the request is granted The interview itself Part 1: Do your research Clip files and archives -- getting bio details beforehand could save time on the actual interview Google the Internet Source lists and Rolodexes Books and magazines (if there’s time) Part 2: Interview requests Often you can just pick up the phone and call. Public officials and politicians are SUPPOSED to serve the public, so they should want give you information Just show up – On breaking news events, you can’t phone first Email requests – Note that emails are discoverable evidence in court. Don’t contact confidential sources via email or use their names in ANY email communications. Letters If any or all of the interview was done by email or letter, you should note that fact in the body of your story. Let the reader judge the credibility of responses given by those contact methods. Example: In an emailed response, Joe Smith denied that the drugs were his. Part 3: They say yes to an interview! Come up with a list of questions, even more than you might need If interviewing in person, pick an appropriate site: the subject’s office or home is most often the choice but sometimes -- on sensitive stories or just for convenience -- a neutral site is best. Note that sometimes the subject’s environment is part of the story. Dress appropriately for the occasion – no need to have a suit at the scene of fire, unless you are a TV type (wearing a bridal gown to Super Bowl media day) Get the equipment you need: tape recorders or notepads? Pens? Batteries? After the request is granted Establish some ground rules a. Bringing a photographer? Translator? A crew? b. Try to set the amount of time required for the interview c. Establish attribution status -- on the record, off the record. See Washington Post handout Part 4: The interview itself 1. Establish a rapport -- the relationship between the reporter and source is crucial to the success of the interview. You have to establish a dialogue between you and the subject. Maybe you can tell about yourself, note common interests, get some small talk going before you broach your topic, be empathetic when appropriate. Be courteous, but you don’t have to put up with discourtesy. Be aware of cultural differences – Muslims consider the bottom of a shoe pointed at them as an insult; some Muslim women avoid shaking hands. Indians do not see interrupting or being interrupted as rude, etc. The interview itself 2. Where you sit could be a factor; figure out how you are going to allow for eye contact. (FBI agent interviewing Saddam “guarded” the door) 3. Be in control of the interview, or at least play for a tie. That’s why you have to know the subject matter and visualize the story beforehand. Some folks like to gab and will get off the subject. 4. Be a good listener; allow room for follow-up questions. Listen to the language used and how it is said. It could reveal a bias or a point a view. Do they keep trying to shift the topic or end discussion? Also, what is not being said can reveal much as well. The interview itself 5. Be observant; the subject’s mannerisms and gestures could add important details to the story or give insight into a hidden part of the subject’s personality. Check pages 72-73 of the text for examples on using your senses. 6. Consider the wording of your question; that will often determine what kind of response you get. Example: “Where did you go to college?” gets one type of response, while “Please tell me about your educational background” gets another. The former is a close-ended question while the latter is an open-ended question. For more on this … Types of questions Close-ended questions get simple “yes” or “no,” either-or type answers, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t important. One of the best close-ended questions you can always ask is “How do you spell your name?” Types of questions Open-ended questions require the subject to answer in more than just a few words. They allow the respondent some flexibility but be careful to make sure they don’t stray or rant. The answers you receive may require you to do follow-up questions for explanation or open up a new line of questioning. Types of questions Loaded questions, also called biased or leading questions in a courtroom, imply that the questioner has already formed an opinion about what the answer should be. “How do you justify voting for the Iraq war without having read the entire National Intelligence Estimate beforehand?” This type could be useful for investigative pieces. “How could you stand by and not help those displaced by the hurricane?” Now, back to interviewing … The interview itself 7. Make sure you understand; it’s OK to get the respondent to repeat something or to stop for a moment. Make sure you can digest the information properly. 8. Be flexible; you never know when an interview might shoot off in another direction. The interview itself 9. Master the wrap-up. Let your subject know they are almost off the hook. “I only have a couple more questions.” OR “Is there anything I was too stupid not to ask that might be useful or helpful to this story?” 10. Remember to thank them for their time and ask if it’s OK to call on them again if necessary. Improving your interviewing technique Listen to the professionals, the folks on the news magazines or the morning talk shows. Observing a good trial lawyer in action, if possible, is a good way to learn how to ask questions. Practice bouncing your questions off friends and colleagues. Practice listening. Using quotes Where do those quote marks go? Do we even need them? Using quotes As we know for the plagiarism segment, we must give credit or attribution when we use someone else’s words. In news stories, these statements are often set off with quotation marks and are teamed with attribution to the source of the quote. The quote marks are a signal to the reader that the words between the marks are just the way the speaker said or wrote them. Using quotes: What they do Why use quotes? Don’t use them just to show your editor you were taking notes during the council meeting. A sentence about a councilman voicing doubts about a program, followed by a quote that says: “I don’t think this will work,” Councilman Green said doesn’t add much to a story. Quotes should add color, assist clarity and enhance the content of a story. They can also be a powerful style tool -and work their way into leads and headlines (like Bush’s Axis of Evil quote from the 2002 State of the Union). Quotes can: Help bring the audience into direct contact with the person speaking, and thus enable the audience to judge the credibility of the subject Capture and communicate a person’s uniqueness Contribute to showing rather than telling (explanation) Can bring personality and passion to issues, demonstrate conflict Humanize a subject -- and also the story Quotes: How long? Quotes should be brief enough to hold the audience’s attention -- unless you are deliberately trying to show how long-winded the subject is. Or, unless you are doing a Q&A type story and you are publishing everything said. News writers often don’t know how to use quotes well -that’s why whenever it’s necessary for you to trim a story, the quotes are often one of the first places you should look. Editing or changing quotes Quotes should rarely, if ever, be rewritten to remove grammatical errors or to change word usage. Quotes are virtually sacrosanct, but if the speaker is a valued source you will use again, why emphasize their mistakes? A little help may be justified in some cases. Some fixes or clarifications can be handled with a parenthetical -- but avoid redundant parentheticals when the information is obvious from the context. You may use ellipses as a tool to bridge from one quote to another or to remove superfluous verbiage -- as long as the meaning remains intact. (Examples to come …) Attributional verbs: Said, said, said There’s nothing wrong with using said over and over. It may seem repetitive, but this allows the reader to focus on the content rather than the attribution. Said provides a sense of neutrality to the reader. Use verbs like announced, stated, argued, explained and other such speech tags only if that accurately represents what the speaker is doing. In news writing, refrain from using body movements and facial expressions as speech tags unless it is part of the story -- like a trial defendant or witness sobbing (Paris Hilton?) in court. In feature writing (your profiles), the shackles on speech tags come off. You can be much less neutral. WARNING!!!! Just because the word “said” is in a sentence does NOT mean you automatically add quote marks. “Said” is merely a verb; it’s a NOT a quote mark generator. “Said” is an acceptable verb in indirect or paraphrased quotes (more on those in a moment) – no quote marks are needed. If you add quote marks to an indirect quote , be prepared for a serious point reduction in your story or AP exercise. Attribution style Print journalists prefer the past tense said, while broadcast favors the present tense says. PR folks use the verb tense that is appropriate for the medium they are writing for. The construction of attribution is nearly always subject / verb. Smith said. But when it’s necessary to add explanation to the attribution, it’s OK to turn it around. As in: “He was a good man,” said Smith, the victim’s cousin. News / PR writers generally use only the subject’s surname on second reference. Some places require courtesy titles. Repeat full names only to avoid confusion (as in quoting a John Smith and a Jane Smith). Attribution style The verb said is the best, but added, continued, explained, predicted, recalled etc. are fine if that is what the subject actually did. The verb claimed can be accurate if that is what the subject is doing -- but it is far less neutral than said. Avoid these verbs: avowed, averred, opined, exclaimed, quipped. Types of Quotes: Direct quote: This is a verbatim statement of what a person says. All text between the begin and end quotes is exactly how a person said something. In the attribution area, try to place long titles after the speaker's name. Many editors prefer placing the noun before the verb in the attribution area, but this is not in stone so be your own judge. Example: "This is one small step for a man," said Neil Armstrong, "but one giant leap for mankind." Types of Quotes: Indirect quote: This is a summary or recap of what was said by a person or persons. The writer edits, condenses and interprets in his own words what was said by someone else. It can set up an actual quote. The verb said can be present, but is not to be taken literally as evidence that something was actually spoken. No quote marks are used. Example: Neil Armstrong said his first steps on the moon signified a historic achievement by mankind. (Note the presence of the verb said even in an indirect quote.) Types of Quotes: Partial quote: This is a sentence that combines the use of direct and indirect quotes. The writer summarizes quoted material in his own words but includes a portion of what was actually stated, often as a way to add emphasis or provide impact. Only the portion of the sentence that was actually spoken is placed between quote marks. Example: Neil Armstrong told the audience that his first steps on the moon were "a giant leap for mankind." Punctuation devices parenthetical: "He (Armstrong) just got back from the moon," she said. Or, if there was only one “he” in the story: “(Armstrong) just got back from the moon,” she said. ellipses: "I can't wait for baseball season to start ... it is my favorite time of year," he said. "It (baseball season) is the best." (The latter is an example of an unneeded parenthetical) Punctuating quotes About 99 percent of the time, punctuation goes inside the ending quote marks. The primary exception is a question form. The placement of question marks with quotes follows logic. If the quote itself is a question, the question mark goes inside the quote. If a statement, however, is turned into a question, then put the punctuation outside the quote marks. EXAMPLES: She asked, "Will you still be my friend?" Do you agree with the saying, "All's fair in love and war"? (Here the question is outside the quote.) NOTE: Only one ending punctuation mark is used with quotation marks. The stronger punctuation mark wins. Therefore, no period after war is used. Online help: www.grammarbook.com/punctuation/quotes.asp Handouts, extra Washington Post’s attribution policy Poynter’s “The way we ask” Types of Quotes Interviewing Exercise Dr. Blakely’s presentation on “Attribution” is on the class site Interviewing exercise Due for the next class. * Worth 5 points on AP exercises OR news quiz grade or 10 points on story grade (writer's choice). Interview a fellow student and find out something relevant, useful or interesting. Emphasize open-ended questions over close-ended questions. Find out something you wouldn't know just by looking at the person. Write about a page on this person, using at least one full quote and two paraphrases. Feel free to use narrative or background sentences. WRITE IN THE THIRD PERSON, NOT FIRST PERSON. Type and double-space the copy. All assignments should be double-spaced Get a phone number or email to get additional information or to help you fact-check (subject will check story in next class)